Bound in Intrigue

Books come and go from libraries, drifting in and out of hands, across continents, and through centuries. The Harvard Botany Libraries contain books whose stories and provenance are a mystery; some of which can be strung together by notes scribbled in the margins, stamps from previous owners, embossing, and distinctive original bindings. While many of our books may have once had fascinating lives, they now sit now safe and dry upon our shelves.

This exhibit highlights a few of the stunning books in our collections.

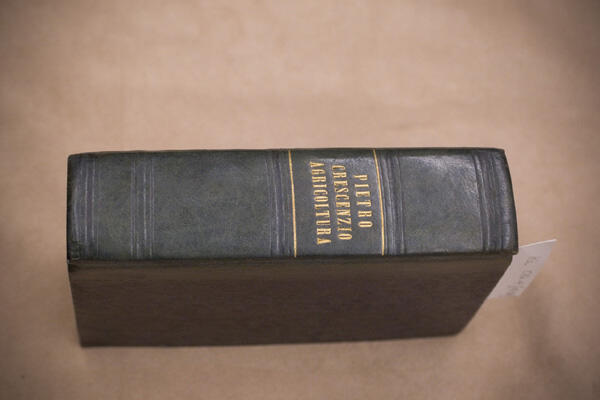

Pietro Crescenzi

Born in Bologna, Crescenzi worked as a judge in that city until his 1299 retirement to a country villa. Ruralia Commoda, which is often referred to by variant titles such as Opus Ruralium Commodorum, was the product of his experience as a landowner. He wrote it late in life; although scholarly opinion regarding the appearance of the first manuscript varies, the earliest date suggested is 1304, when he would have been about seventy years old. Crescenzi wrote in Latin, the universal scholarly language of the day, but his words were quickly translated into numerous European languages.

Illustrations

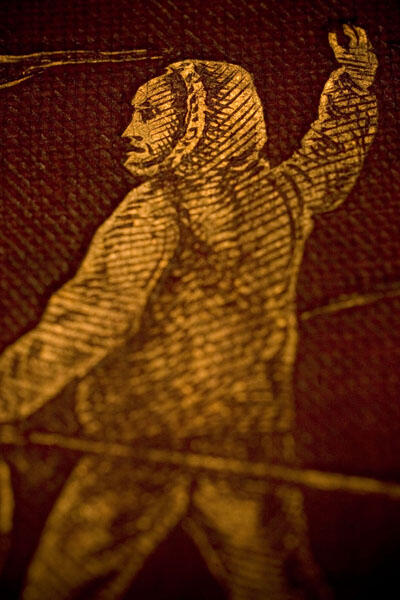

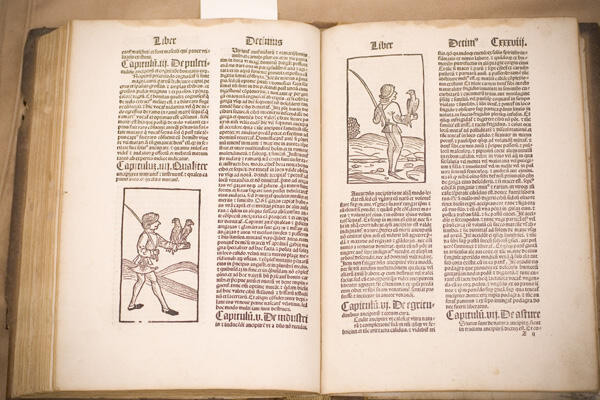

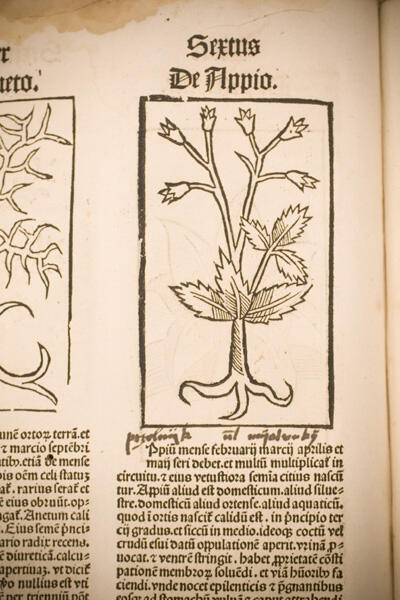

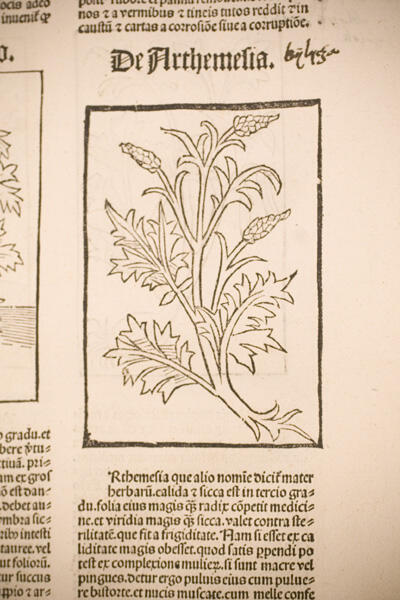

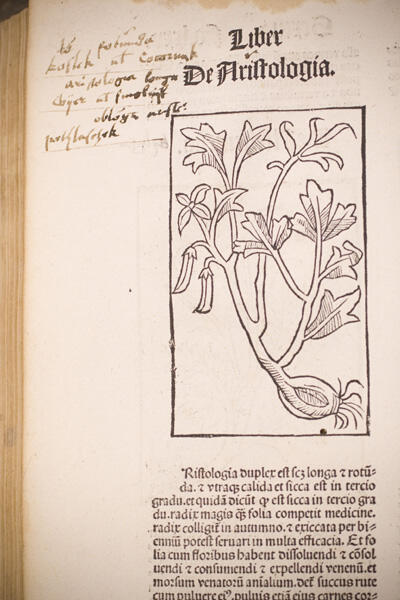

Manuscript copies of Ruralia Commoda were popular (over 100 copies are known), making it an excellent candidate for the new technology of printing. The editio princeps appeared in 1471: in Latin, un-illustrated, it was printed by Johann Schüssler of Augsburg. Another 36 incunable editions exist, most printed in Germany. Peter Drach of Speyer printed a German-language edition in 1493; this edition has 234 woodcuts. Drach's workshop (one of the period's most prominent) also printed a Latin edition that utilized the same woodcuts, and the Library of the Arnold Arboretum's incunable was part of that edition (similar copies exist in the Royal Collection and in the library of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden). The text is arranged in two columns throughout, and blank spaces have been left at the beginning of each chapter for an initial (in the Library of the Arnold Arboretum's copy a previous owner has added the first few initials of Book 1 by hand).

Arnold Klebs describes the plentiful woodcuts - they occur at the beginning of most of the chapters - as "the most remarkable group of middle Rhenish woodcutting in the 15th century." Dating of the illustrated Latin edition is difficult: did it precede or follow the German edition of 1493? Anderson prefers the Latin version to antedate the German version. But the Latin version has more woodcuts (primarily in Book 10, on hunting, fishing, and falconry), which may indicate that it post-dates the German.

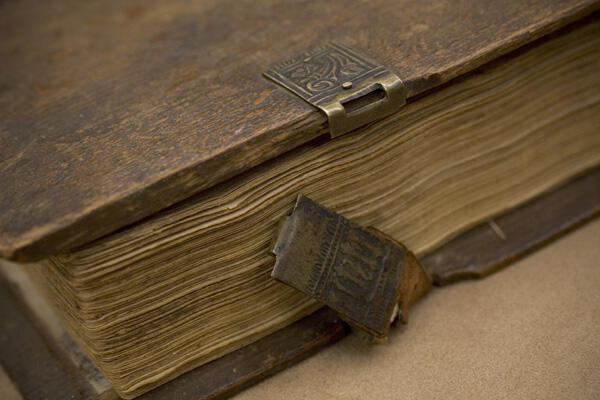

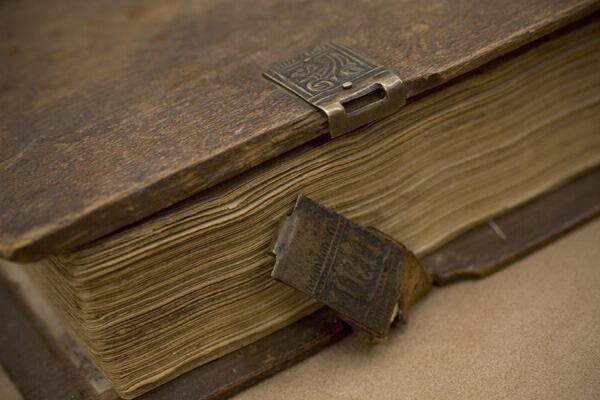

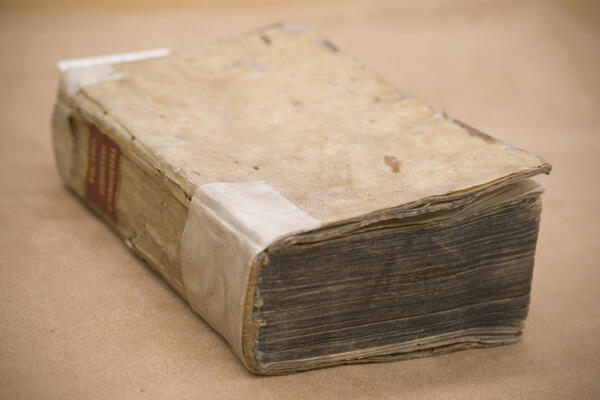

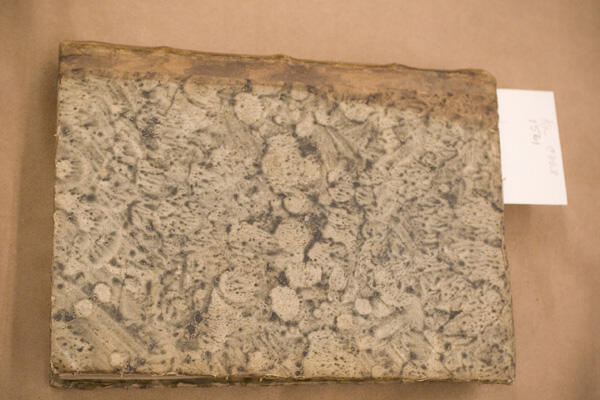

Incunable binding

When and where was it bound? The binding is of the "schoolbook type," half-leather (probably calfskin) over oak boards. Thick oak boards with beveled edges, brown calfskin with pictorial blind-tooling, double cords and catch/clasp fastenings are all typical of 15th-century Northern European bindings. This style dates the binding to approximately the same time and place as the textblock. The oak boards may indicate that this binding was a product of Germany's once-vast oak forests and that it was bound relatively close to where it was printed.

The Library of the Arnold Arboretum's Crecenzi incunable binding: Spine, Calfskin with blind-tooling, Clasp.

Certain touches indicate that the book held special importance for its owner: the embossed brass catches and clasps and the elaborate blind-stamped images of a hunt scene, for example. The style and components of the binding suggest that it is original to the textblock. Repairs were done to the book, perhaps in the early 20th century. Along with many of the Library of the Arnold Arboretum's finest holdings, it was transferred to Houghton Library in 1947, and came to its present location on Divinity Avenue in 2006.

Other bindings

Other editions of Crescenzi books owned by the Library of the Arnold Arboretum testify to the enduring popularity of his text in the centuries following its initial publication. Ruralia Commoda was frequently published in Italian, French, and German translations (several of the Library of the Arnold Arboretum copies are in Italian). In many cases the content was revised and updated but still credited to Crescenzi. Introductions appeared, penned by great names of the day. Some editions - such as the 1561 edition in the Library of the Arnold Arboretum - include glossaries of vocabulary to help a reader navigate the intricacies of agriculture, indicating that it was a book used less often by farmers than by gentlemen with an interest in farms. (It combined the features of an herbal with those of a pastoral.) And, in some cases, individual books of the original twelve were published on their own, as in the case of the Library of the Arnold Arboretum's nineteenth-century French translation of Book 4 (on wine-making).

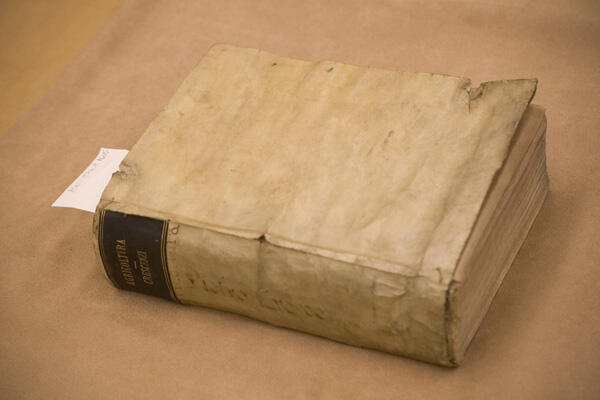

These books often reveal a history of use in the corners of pages worn smooth by touch, in underlining and other nota bene marks, in the subject-specific marginalia. The incunable has handwritten Slavic translations for a variety of herbs in Book 6, and one reader of the 1605 edition has re-written segments of the Italian text in the margins, as if to commit them to memory. The parchment bindings that survive from the 16th century show the wear and tear of centuries' use. They are also object lessons in the durability of many utilitarian, "temporary" bindings, which may indicate the role of Crescenzi's text as a reference book: not the most elegant book in any collection but one that was consulted frequently and that needed to be protected from the rigors of use.

Examples of a Crecenzi parchment binding from the Library of the Arnold Arboretum

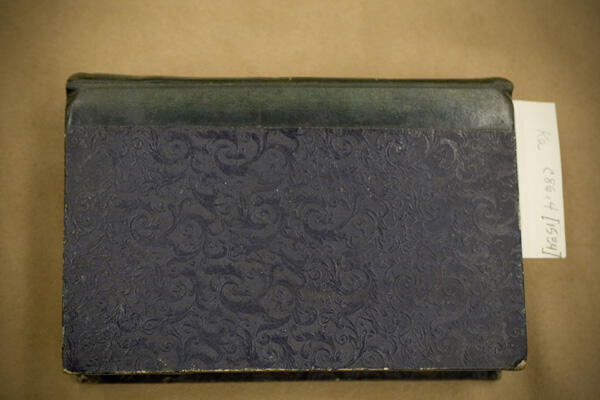

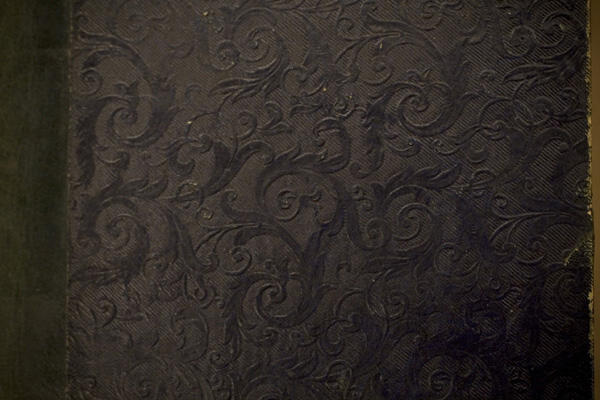

The bookbindings of the Crescenzi books also testify to the enduring value of the book's text to many generations of readers. The 1534 edition, donated by Sarah C. Sears, is centuries removed from its original binding, and is cased in green leather and Victorian book cloth with an embossed floral motif: this is not a fine binding but it demonstrates that someone wanted to keep the text safe from further damage.

The 1534 Crecenzi binding from the Library of the Arnold Arboretum

The 1561 edition was rebound in 18th-century daubed and pulled paste paper and a leather spine with (rather lopsided) gold tooling. A much later example is the library binding of the nineteenth-century "Le quatrième livre du Rustican consacré à la vigne," a none-to-elegant example of a previous era's approach to preservation. The cardboard covers serve the purpose of keeping the textblock safe, and the book opens in a pleasant way that encourages reading. In this case, a library binding has been used to protect an article excerpted from a larger publication. It is just a shame that on so many occasions earlier binding materials were discarded in the process of rebinding the textblock.

The Library of the Arnold Arboretum's 1561 Crecenzi binding and the 19th century Crecenzi binding

Sources

Anderson, Frank J. An Illustrated History of the Herbals. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.

Cockerell, Douglas. Bookbinding, and the Care of Books; A Text-Book for Bookbinders and Librarians. London: Pitman, 1953.

Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. New York: Dover Publications, 1980.

Greenfield, Jane. ABC of Bookbinding: A Unique Glossary with Over 700 Illustrations for Collectors & Librarians. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1998.

Dr. Jörn Günther, Antiquariat. "42 Petrus de Crescentiis, Ruralia commoda - In commodum ruralium cum figuris libri duodecim." Dr. Jörn Günther, Antiquariat. http://guenther-rarebooks.com/catalog-online-09/42.php (accessed April 26, 2009).

Klebs, Arnold C. A Catalogue of Early Herbals: Mostly from the Well-Known Library of Dr. Karl Becher, Karlsbad; with an Introduction by Arnold C. Klebs. Art Ancien Bulletin, 12. Lugano: Art Ancien, 1925. No. 60 is the 1493 German edition which shares woodcuts with the Library of the Arnold Arboretum's incunable.

Szirmai, J.A. The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate, 1999.

Tomlinson, William, and Richard Masters. Bookcloth 1823-1980: A Study of Early Use and the Rise of Manufacture, Winterbottom's Dominance of the Trade in Britain and America, Production Methods and Costs and the Identification of Qualities and Designs. Stockport, Cheshure, Englad: D. Tomlinson, 1996.Ames bookbindings

This portion of the exhibit describes some of the more intriguing bindings from the Botany Libraries and Archives collections.

Alfred de Sauty

Details from the interior of the book

Alfred de Sauty (1870-1949) was a bookbinder who produced tooled bindings of exceptional delicacy. De Sauty was active in London from approximately 1898 to 1923 and in Chicago from 1923 to 1935. His finest work is thought to be have been accomplished between 1905 and 1914. Many aspects of his life are poorly documented. For instance, scholars are unsure whether, when in London, de Sauty worked independently, for the firm of Riviere & Sons, or both. While in London, he may also have been a designer for the Hampstead Bindery and a teacher at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. When he lived in Chicago, de Sauty worked for the hand bindery of R. R. Donnelley & Sons. He signed his work at the foot of the front doublure, if present, and at the center of the bottom turn-in of the front upper board, if not. Works he produced in London are signed "de S" or "De Sauty." Works he produced in Chicago are signed with his employer's name, "R. R. Donnelly."

Previous owners

The Curious and Profitable Gardener

There are several criteria by which a book can be deemed "rare" or "exceptional." It could be one of a small number printed in a certain year. It could be signed by the author. It could have a remarkable or unique binding. It could have been owned, in the course of its life, by a well-known person.

The volume of The Curious and Profitable Gardener owned by the Botany Libraries is of historical interest for the text it contains, one of its known previous owners, and the bookbinder who created its current binding. It was previously owned by Oakes Ames (1874-1950), a respected American botanist who specialized in the study of orchids. Ames was very interested in the field of economic botany and spent his entire professional career at Harvard University. He was married to Blanche Ames, an accomplished artist, and together they amassed a large botanical library. In the early 20th century, Ames had a number of his early 15th to 18th century botanical works rebound in fine leather bindings to suit his own particular aesthetic tastes. This particular volume came to the Botany Libraries in 1918 when Ames donated a collection of economic botany material from his personal library.

The book itself

The Curious and Profitable Gardener was authored by John Cowell. This volume was printed in 1730 in London for Weaver Bickerton and R. Montagu.

The copy owned by the Botany Libraries is bound in brown goatskin with a central green circular decorative medallion. The medallion depicts a standing man bent over facing right holding a shovel. The decoration on the front and back covers is identical. The covers, spine, inside front cover (turn-ins), inside back cover (turn-ins), headcap, and all edges are tooled in gold. The exterior borders on each cover are composed of double straight lines tooled in gold. There are blossoms tooled in blind in each of the four corners. The spine is rounded and tight-backed. The binder's stamp "De Sauty" is centered on the lower turn-in of the front upper board.

The volume is in good condition. The leather is slightly scuffed in several places, particularly on corners and edges. The headcap at the tail is slightly cracked. This is a laced in binding, and the book opens well. It is sewn with white thread, probably cotton. There are double headbands at both the head and tail, made of red and brown thread, possibly silk. There is some acid migration from the leather turn-ins on both the front and back end sheets. There is moderate foxing of the text block paper. There is no evidence of tears and the paper is not brittle.

This book has been completely rebound. New endsheets have been added. The text block has not been trimmed.

Detail from cover

Dating the book

When was The Curious and Profitable Gardener bound? We can determine an approximate date for this bookbinding by applying some logical reasoning. We know that Alfred de Sauty worked in London from approximately 1898 to 1923. We also know that his finest work was accomplished between 1905 and 1914. This binding is most likely done in London because it is signed "De Sauty." The binding must have been made prior to 1918, when Oakes Ames donated it to the Harvard University Botany Libraries. These circumstances give us a nice terminus post quem (limit after which) and terminus ante quem (limit before which) of broadly 1898-1918. Based on the style and material of the bindings, as well as what we know about Oakes Ames's life, the range of circa 1900-1917 is most likely. To date, no relevant archival material has been found that would definitely answer this question. Barring further information, this general date range is as specific as one can be.

This bookbinding is a nice example of an early 20th century, English, fine, leather binding. However, one can not help but wonder what earlier binding materials were discarded in the rebinding process.

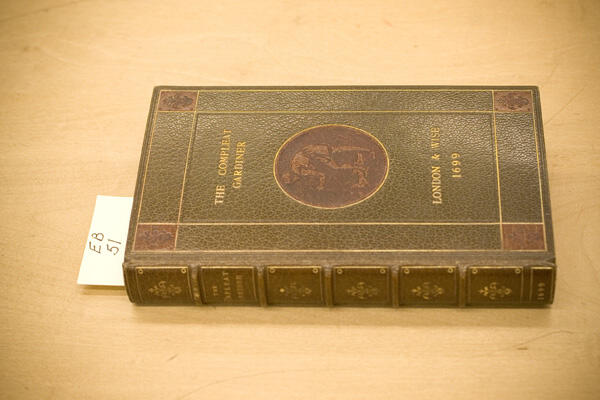

The Compleat Gard'ner

The Compleat Gard'ner, or, Directions for cultivating and right order of fruit-gardens, and kitchen gardens was authored by Jean de La Quintinie (1626 to 1688). This volume was printed in 1699 in London for M. Gillyflower, and sold by Andrew Bell.

The copy owned by the Botany Libraries is bound in a reddish brown Morocco goatskin with a central reddish circular decorative inlaid medallion. The medallion depicts a standing man bent over facing left with a fruit tree in front of him and a basket of tools behind him. The decoration on the front and back covers is identical. The covers, spine, inside front cover (turn-ins), headcap, and all edges are tooled in gold. The exterior borders on each cover are composed of double straight lines, one gold-tooled and the other blind-tooled. The inlaid central medallion is surrounded by a single border tooled in gold. Blind-tooled fleur-de-lys appear in each of the four corners. The spine is divided into six panels by five raised bands. The sixth panel, which is nearest the tail of the spine, is larger than the other panels. The title of the book is tooled in gold on the second panel of the spine. The date of publication is tooled in gold on the sixth panel of the spine. The binder's stamp "De Sauty" is centered on the lower turn-in of the front upper board.

The volume is in good condition. The leather is slightly scuffed in several places, particularly on corners and edges. This is a laced in binding, and the book does not open well. It is sewn with white thread, probably cotton. There is a single headband at the head and tail made of green and yellow thread, possibly silk. There is some acid migration from the leather turn-ins on both the front and back end sheets, and extreme foxing of the text block paper which has led to a darkening of some pages. There is no evidence of tears, and the paper is not brittle.

This book has been completely rebound. New endsheets have been added. The text block has not been trimmed.

Detail from cover

Sources

Alfred de Sauty

Greenfield, Jane. ABC of Bookbinding: A Unique Glossary with over 700 Illustrations for Collectors and Librarians. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1998.

Lhotka, Edward R. ABC of Leather Bookbinding: An Illustrated Manual on Traditional Bookbinding. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2000.

Maggs Brothers. Bookbinding in the British Isles. London: Maggs Brothers, 1987.

Tidcombe, Marianne. "The Mysterious Mr. De Sauty." in David Pearson, ed., For the Love of the Binding: Studies in Bookbinding History Presented to Mirjam Foot. (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press), 329-336.

Oakes Ames

Plimpton, Pauline Ames and George Plimpton. Oakes Ames. Jottings of a Harvard Botanist. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

Sax, Karl. "Oakes Ames (1874-1950)." Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 31 (1950): 335-337.

Schultes, Richard Evans, Pauline Ames Plimpton, Gordon W. Dillon, Leslie A. Garay, and Gustavo Romero-González. Orchids at Christmas. Harvard University: Botanical Museum of Harvard University, 1975.

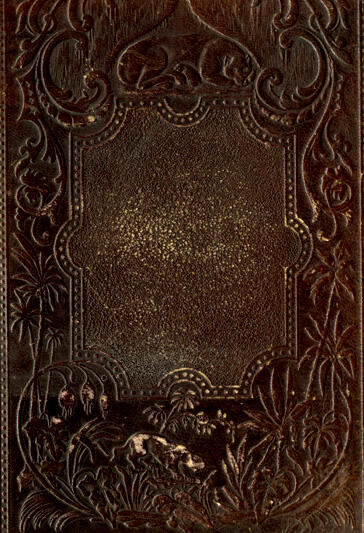

Book covers

This portion of the exhibit displays some of the beautiful book covers from the Botany Libraries collections.

Travels in the East Indian Archipelago by Albert Smith Bickmore

|

|

|

|

Details from cover

From the book ...

"The Battas certainly do not eat human flesh for lack of food, nor wholly to satisfy revenge, but chiefly to gratify their appetites. The governor at Padang informed me that these people gave him this odd origin of their cannibal customs: Many years ago one of their rajahs committed a great crime, and it was evident to all that, exalted as he was, he ought to be punished, but no one would take upon himself the responsibility to punish a prince. After much consultation they at last hit upon the happy idea that he should be put to death, but they would all eat a piece of his body, and in this way all would share in punishing him. During this feast each one, to his astonishment, found the portion assigned him a most palatable morsel, and they all agreed that whenever another convict was to be put to death they would allow themselves to gratify their appetites again in the same manner, and thus arose the custom which has been handed down from one generation to another till the present day."

Natural History Rambles: Ponds and Ditches by Mordecai Cubitt Cooke

Detail from cover

From the book...

"It is not easy to define in a few words the area over which our wanderings are intended to extend; this will become more evident from a perusal of the whole work. It may be premised, however, that in commons, marshes, and low districts, there are miles after miles of ditches which have no perceptible current, only varying in height, not with the tides, but only with wet or dry seasons; ditches in which vegetation appears to run wild, three-fourths of the surface being covered with the leaves of aquatic plants, or a green scum, and whose dark waters, impregnated with the decay of plants, have sometimes an unmistakable odour. Such ditches swarm with living creatures too numerous for more than a small portion to come under our notice."

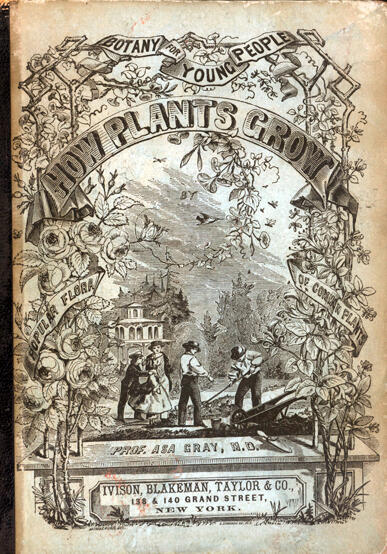

Botany for Young People and Common Schools: How Plants Grow by Asa Gray

Detail from cover

Detail from cover

From the book ...

"Considering of plants inquiringly and intelligently is the study of Botany. It is an easy study, when pursued in the right way and with diligent attention. There is no difficulty in understanding how plants grow, and are nourished by the ground, the rain, and the air; nor in learning what their parts are, and how they are adapted to each other and the way the plant lives. And any young person who will take some pains about it may learn to distinguish all our common plants into their kinds, and find out their names.

"Interesting as this study is to all, it must be particularly so to Young People. It appeals to their natural curiosity, to their lively desire of knowing about things: it calls out and directs (i.e. educates) their powers of observation, and is adapted to sharpen and exercise, in a very pleasant way, the faculty of discrimination. To learn how to observe and how to distinguish things correctly, is the greater part of education, and is that in which people otherwise well educated are apt to be surprisingly deficient. Natural objects, everywhere present and endless in variety, afford the best field for practice; and the study when young, first of Botany, and afterwards of other Natural Sciences, as they are called, is the best training that can be in these respects. This study ought to begin even before the study of language. For to distinguish things scientifically (that is, carefully and accurately) is simpler than to distinguish ideas. And in Natural History the learner is gradually led from the observation of things, up to the study of ideas or the relations of things.

"This book is intended to teach Young People how to begin to read, with pleasures and advantages, one large and easy chapter in the open Book of Nature; namely, that in which the wisdom and goodness of the Creator are plainly written in the Vegetable Kingdom."

The Polar and Tropical Worlds: A Description of Man and Nature by Georg Hartwig

Details from cover

From the book...

"The she-bear is taught by a wonderful instinct to shelter her young under the snow. Towards the month of December she retreats to the side of a rock, where, by dint of scraping and allowing the snow to fall upon her, she forms a cell in which to reside the winter. There is no fear that she should be stifled for want of air, for the warmth of her breath always keeps a small passage open, and the snow, instead of forming a thick uniform sheet, is broken by a little hole, round which is collected a mass of glittering hoar-frost, caused by the congelation of the breath. Within this nursery she produces her young, and remains with them beneath the snow until the month of March, when she emerges into the open air with her baby bears."

Ling-Nam by Benjamin Couch Henry

Detail from cover

Detail from cover

From the book...

"Below us tumbles the mountain stream, gathering in deep pools or rushing over great boulders. Above us rises the fern-clad slope, thickly overgrown. Another pavilion is soon reached, from which we catch our first glimpse of the delightful waterfall called "Fi-shui," "Falling Water". The water flowing down from the height above falls over a broad wall of rock about fifty feet into a large emerald pool. Masses of ferns, begonias, and orchids line the bordering rocks. From stone to stone we step until the spray of the falling water dashes its cool drops over our faces, upturned to gaze and admire. The ledge of the rock on which we stand forms the starting-point of another cascade, which pours into a deep circular basin, an ideal swimming bath. The transparent water gives no clue to its depth, and not until an umbrella, accidentally dropped, sinks to the bottom, and unsuccessful efforts to recover it are made, do we realize how deep it is. An expert diver at last secures it, and reveals the fact that the water is from fifteen to twenty feet deep in that crystal basin."

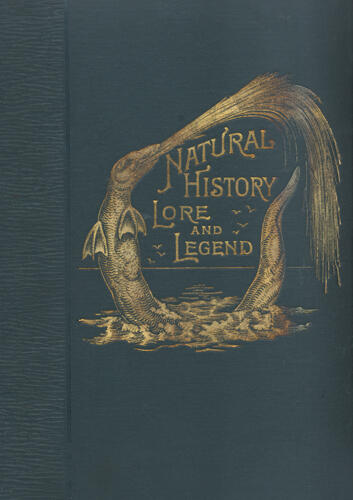

Natural History, Lore and Legend by Edward F. Hulme

Detail from cover

From the book...

"Even the dragon, however, may not be quite so black as he is painted, for we read in one old author of a child in Arcadia that had a dragon for its playmate. There was much affection between them, but presently a considerable dread of the dragon's powers gained possession of the boy, and he compassed the brilliant idea of beguiling his companion well out into the desert and then slipping away. In the very consummation of this plan a new danger arose, as the stripling found himself in an ambush of robbers, whereupon he was only too thankful to call out to his discarded playmate, who immediately came to the rescue and very effectually scattered his despoilers. At this point the history unfortunately stops, but we may perhaps conclude that it follows on the lines of most stories of the affections, and that "they lived happy every after." However this may be, it is a charming narrative, and opens out quite a trait of dragon disposition."

Studies of Trees in Winter by Annie Oakes Huntington

Detail from cover

Detail from cover

From the book ...

"Outside my window the trees in a little wood stand leafless. Everything which made this wood a delight in June, the contrast of light and share among the leaves, the varying tones of green in broken sunlight, the warmth and color and summer freshness, has gone, but the trees themselves, in all their wealth of foliage were never so beautiful as now. The massive moulding of their trunks, the graceful curves of their branches, the fine tracery of their little bare twigs, now clear against the sky and again lost in a tangled network of intersecting branches, the whole beauty of their symmetry, their poise, strength, and delicacy is revealed as it is never revealed in summer."Attracted first by the obvious grace of the forms of trees as we see them from our windows in winter, we discover that a closer study of the details of bare twigs and buds in the woods discloses unsuspected beauty in texture, form, and color. Each tree has definite traits of its own which distinguish it from every other tree, and by tracing individual characteristics in the branches, trunk, stems, buds, and leaf-scars we are able to identify every tree with certainty."

A Tour Round My Garden by Alphonse Karr

Detail from cover

Detail from cover

From the book ...

"I thought of all the riches which God has given to the poor; of the earth, with its mossy and verdant carpets, its trees, its flowers, its perfumes; of the heavens, with aspects so various and so magnificent; and of all those eternal splendours which the rich man has no power to augment, and which so far transcend all he is able to buy."I thought of the exquisite delicacy of my senses, which enables me to enjoy these noble and pure delights, in all their wants and desires; the richest, most secure and most independent of fortunes. And, with joined and clasped hands, with eyes raised towards the gradually darkening heavens, with a heart filled with joy, serenity, and thankfulness, I implored pardon of God for my murmurings and my ingratitude, and offered up my grateful thanks for all the enjoyments he had lavished upon me.

"And as I sunk to sleep that night, my spirit was filled with pity for those poor rich."

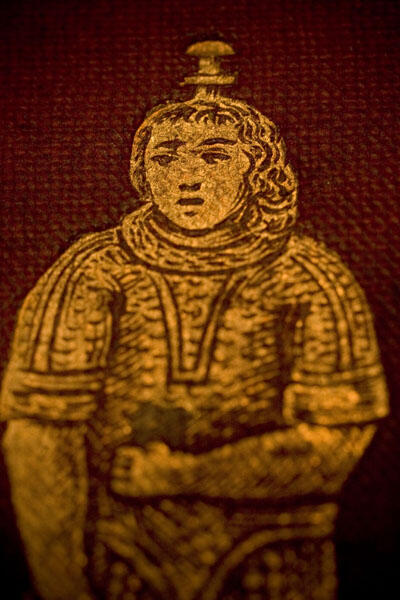

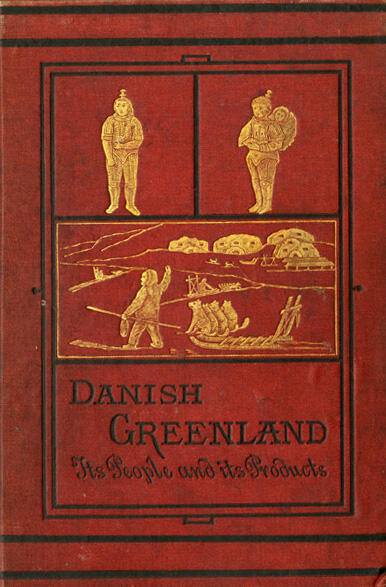

Danish Greenland: its people and products by Hinrich Rink

|

|

|

|

Details from cover

From the book ...

"Very doubtful and scanty remains have hitherto been found on the North American continent itself, which bear witness to its having been visited by voyagers from this side of the ocean, and even to its having been inhabited by European settlers several hundred years before the discovery of America by Columbus. Our sole knowledge of these ancient enterprises has been derived from the Icelandic sagas, or popular tales. These sources of inestimable value, on account of their having been written down at so early a period, when the events related in them were still fresh remembrance, though historical, exist of course only in a fragmentary condition, and bear the general character of popular traditions to such a degree that they stand much in need of being corroborated by collateral proofs if we are wholly to rely upon them in such a question as an ancient colonization of America."

Field Book of Common Gilled Mushrooms by William S. Thomas

Detail from cover

From the book ...

"Mushrooms of one kind or another are to be found at almost every season but they occur in greatest abundance after showery weather in the months of July, August and September."The collector will find a basket to be a good receptacle for them and different species may be kept separate from each other and uncrushed by having leaves or leafy twigs among them, or better yet, by being carried in paper bags. Folding paper boxes, such as are used for holding crackers are also good for this purpose.

"The mushroom is plucked entire from the ground or wood upon which it grows and especial care much be taken not to cut or break the stem. Unless the whole plant is obtained it will be difficult or impossible to know whether the stem is provided with volva or cup at the base, or whether its base is bulbose or hairy or attached to other stems. The dirt adhering to the stem, if there is any, is removed before the specimen is put with others into the receptacle. In collecting mushrooms for the table, the stems are cut off close to the cap.

"The beginner is warned against attempting to identify a new species with but one or two specimens at hand. It is desirable to have for this purpose several specimens of varied stages of development, so that one or more of them may be cut across in order that the form of the gills and interior of the stem may be noted, while yet other caps may be needed for spore prints. It is important to keep separate from each other the specimens of the various species collected."

Im Afrikanischen Urwald by Franz Thonner

Detail from cover

Franz Thonner was an Austrian botanist who wrote a number of keys to genera and families of flowering plants. He was born in 1863 and died in 1928. He made trips to the Congo to study botany. (New Phytologist, v 93, 1983) In 1896 he accomplished an important journey through the Congo basin, described in Im Afrikanischem Urwald. Twelve years later he returned to Africa to continue his studies. His health failed him upon this journey and he was forced to return home sooner than he wanted. Besides his botanical collections, he had also mapped the route between Mandungu and Yakoma, and made numerous meteorological observations, as well as obtaining vocabularies of twenty dialects. (Journal of the African Society, 1911)

This volume was printed in Berlin in 1898. From a pencil inscription on the interior we learn that it was acquired by the Harvard Botany Libraries in September of 1907. It is printed in German, and contains beautiful illustrations as well as 86 stunning photographs taken by the author depicting the people of Africa, their homes, lives, and tools.

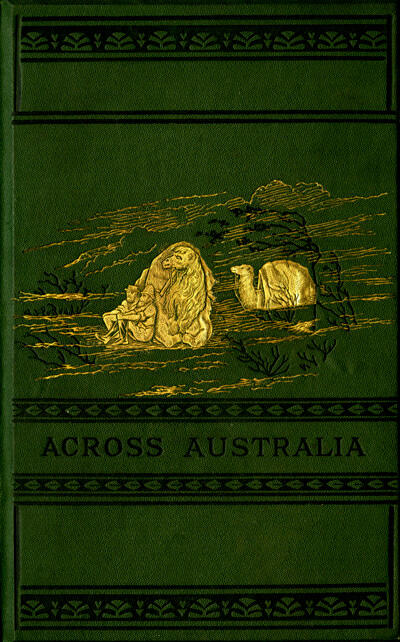

Journey Across the Western Interior of Australia by Peter Egerton Warburton

|

|

|

|

Details from cover

From the book ...

"We made another effort at daylight to get on, but one of the camels broke down, though it had not carried a saddle. The poor beast had become quite blind, and staggered about in a most alarming way. We could not get her beyond a mile and a half, when she knocked up under the shade of a bush, and would go no farther. We therefore also sat down to await the water to be sent out to us. The heat was intense, and my son, having been obliged to walk because the camel could not carry him, suffered very greatly from thirst, and had not water been brought us before midday, it would have gone ill with him. Between 10 and 11 a.m. Lewis returned with water from the well.

"The camel, though we gave it some water, could not move from the shade of the bush. We tried to drive it, and to drag it, but to no purpose, therefore we shot it. My son and White returned to the well for more water and to bring out camels to carry the meat. Lewis remained with me to cut up the camel and prepare it for carriage. We sent the head and tail, with the liver and half the heart and kidneys, to make soup for Charley, and a little picking for the rest. I hope the fact of the camel's head not having been turned towards Mecca, or its throat cut by a "True Beliver," may not prejudice the camel-men against the use of what we send.

"Cutting up the camel, and eating the "tit-bits" was the work of the day. We have now only five camels, and one of them so weak it cannot carry a saddle. Could we but reach Oakover, we might manage some way or other, but the camels must take us there, or we shall never see it. I am sanguine now that we shall get there with at least four camels; two days ago I never expected to be able to leave the spot I was lying upon."

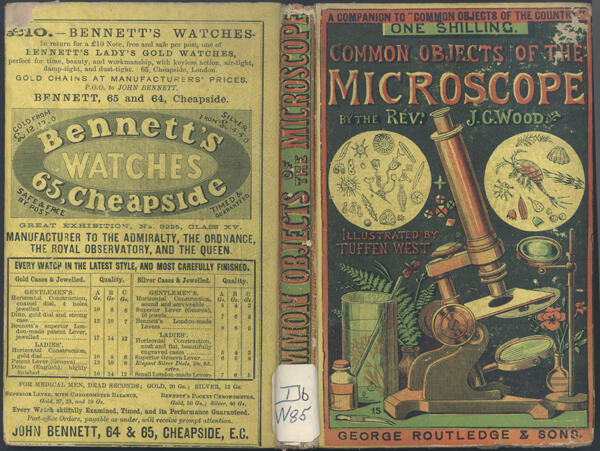

Common Objects of the Microscope by John George Wood

|

|

|

|

Details from cover

From the book ...

"No pen, pencil, or brush, however skillfully wielded, can reproduce the soft, glowing radiance, the delicate pearly translucency, or the flashing effulgence of living and ever-changing light with which God wills to imbue even the smallest of his creatures, whose very existence has been hidden for countless ages from the inquisitive research of man, and whose wondrous beauty astonishes and delights the eye, and fills the heart with awe and adoration."

A Naturalist Among the Head-Hunters by Charles Morris Woodford

|

|

|

|

Details from cover

From the book ...

"Packing up my camera and placing it in the boat, I get a boy to carry my gun, and taking the insect-net myself, start for a short walk through the yam gardens and forest immediately at the back of the village. Half a dozen imps of boys attempt to accompany me, but I tell them I do not want them, as their continual chatter would prevent me getting within sight of any bird. Some seem reluctant to leave me, but at last, after some disparaging remarks hurled as a Parthian shot at the head of the boy who is carrying the fun, they drop away.

"I have a delightful ramble along the forest tracks for a couple of hours, during which I fill my collecting-box, and as I know what to discard, most of the insects caught are of rare or local species. I also shoot three or four specimens of a fly-catcher with chestnut body, grey wings, and white head, which appears strange to me, and afterwards proves to be a new species, which has been named by Mr. Sharp Pomarea Florentiae, after my wife.

"I notice a large orchid growing high out of reach upon a dead tree. It is apparently a Grammatophyllum, a stranger hitherto to me, but afterwards found to be not umcommon upon other islands. It was finished flowering, but the sight of the great seed-pods, as large as ducks' eggs, hanging from the flower-spike, make me long to see it in bloom. My attendant sprite expresses himself unable or unwilling to climb the tree, although I hint at untold wealth of tobacco as recompense.

"I am engaged in the attempt to compass somehow or other the attainment of the orchid in question, when a sudden tropical shower forces me to seek shelter somewhere."

Sources

Bickmore, Albert Smith. Travels in the East Indian Archipelago. New York. 1869.

Cooke, Mordecai Cubitt. Ponds and ditches. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York, Pott, Young, 1880.

Gray, Asa. Botany for Young People and Common Schools: how plants grow, a simple introduction to structural botany. New York: Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor & Co., 1874.

Hartwig, G. The Polar and Tropical Worlds: a description of man and nature in the polar and equatorial regions of the globe. Springfield, Massachusetts, Bill, Nichols & Co., 1872.

Henry, B.C. Ling-Nam. London, 1886.

Hulme, F.E. Natural History, Lore and Legend. London, 1895.

Huntington, Annie Oakes. Studies of trees in winter; a description of the deciduous trees of northeastern America. Boston, Knight and Millet, 1902.

Karr, Alphonse. A Tour Round My Garden. London: Frederick Warne, 18--?

Rink, Hinrich. Danish Greenland: Its People and Its Products. London: H.S. King & Co., 1877.

Thomas, William Sturgis. Field Book of Common Gilled Mushrooms, with a key to their identification and directions for cooking those that are edible. New York, London, G.P. Putnam's sons, 1928.

Thonner, Franz. Im Afrikanischen Urwald. Berlin, 1898.

Warburton, Peter Egerton. Journey Across the Western Interior of Australia. London. 1875.

Wood, John George. Common Objects of the Microscope. London, New York, G. Routledge & Sons, 1861.

Woodford, Charles Morris. A Naturalist Among the Head-Hunters. London: G. Philip & Son, 1890.