History of Mycological Illustration

In a paper read before the Botanical Society of Washington, D.C. in December 1921, mycologist L. C. C. Krieger pointed out that illustrations are essential for the correct identification of fleshy fungi. He noted that the best illustrations accurately portray the organism's size, shape, color, and other physical characteristics.

Unfortunately, early naturalists faced many obstacles in their attempts to document the fungi they observed. They often lacked fresh specimens, had use of only primitive printing techniques, and in some cases, suffered from overactive imaginations!

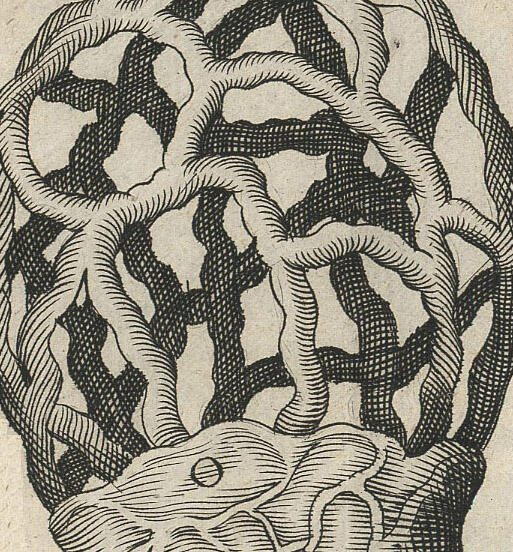

The earliest example of a printed fungus appears in the work, Ortus Sanitatis (1491) and was created using the technique of wood block printing. The process begins by drawing or tracing the subject onto the surface of a block of wood, and then the lines or areas that are to be left white or unprinted are cut away with a knife or gouge. Ink is rolled over the wood block design and the block is pressed onto the paper to complete the printing process. The resulting black and white image is often quite striking, but lacks the detail to identify species. Nevertheless, the process was in general use throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.

Early naturalists were not only hampered by their inability to produce precise colored images of fungi; they also had to measure the fanciful notions promulgated by contemporary herbalists. One of the most amusing of these is the work of Dr. Georgius Seger (plate 1). In his work, Anthropomorphus, Seger illustrates a geaster, or star fungi, bursting open to free the tiny men and women who seem to be trapped inside. While the image does hold a certain charm, it does nothing to advance the serious study of mycology.

The work of illustrators was greatly enhanced by the introduction of steel and copperplate engraving in the 17th century. This method involves cutting lines into the copper to create what is known as a burr. The carved lines hold the ink, rather than the raised surfaces in wood black printing, to create a more refined image. Shading is be added by crosshatching the metal to achieve a greater sense of form and depth. The finished plate is inked and pressed against the paper, and then run through two rollers to produce a clean, sharp image. Still, these images were of limited use unless colored by hand.

By the mid 18th century a method was devised to add color to the engraved plate. Johann Wilhelm Weinmann (1683-1741), was the first mycologist use this method in his Phytanthoza Iconographia (1737-1745). Unfortunately, his illustrations lacked both accuracy and clarity, and proved that another method for color printing was needed.

The quality of mycological illustration did improve in the late 1700's because naturalists employed artists to hand color plates. These illustrations were generally more accurate and identifiable, but the practice was costly, time consuming, and often lacked consistency. The colorists often painted the plates differently. In some cases the differences were subtle, but there were many examples of the same mushroom portrayed in totally different colors.

Jacob Christian Schaeffer (1718-1790) was one of the earliest mycologists to use this technique in his work Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu circa Ratisbonam nascuntur icones. Notice that the plates in this exhibit are each colored slightly differently.

Printing was revolutionized in the 1800's with the birth of lithographic printing. The process of lithography was actually invented in 1798 by Bavarian actor Alois Senfelder, but he kept it a secret until about 1818. Senfelder's use of his invention was so poor that lithography did not catch on until the mid-1800s.

The lithographic process is much different from the earlier methods of printing. Colored inks are applied to a grease-treated image on a flat printing surface. Blank areas that hold moisture repel the lithographic ink. The inked surface is then printed directly onto paper. Finally, mycologists had a technique that gave them necessary detail and consistent application of color. The earliest examples of mycological lithographs are from the 1860s.

All these printing tools did not necessarily ensure quality. Look to Max Britzelmayr's Hymenomyceten aus Sudbayern (Plate 2) published in 1895. C.G. Lloyd pronounced it the "poorest excuse for an illustrated work on fungi" that he had ever seen. Many works were published during the age of lithography, some superlative but others very rudimentary.

The dawn of the 20th century brought a host of new printing processes. Collotype, heliotype, and half-tone were just a few, but none had the impact on the nature of scientific illustration as lithography - until the introduction of photography.

Colored photographs provided scientists with a true view of their specimens. Now scientists were able to combine photographs with illustrations to provide other mycologists with the most accurate and detailed view.

Ortus Sanitatis. De Herbis et Plantis...(1491)

1491

1st published illustration of a fungus

Plate: Fungus [woodcut]

Ortus Sanitatis. De Herbis et Plantis. De Animalibus et Reptilibus. De Avibus et Volatilibus. De Piscibus et Natatilibus. De Llapidibus et in Terre Venis Nascentibus. De Urinis et Earum Speciebus.

[Moguntia. 1491.]

Image taken from the later,1517 edition

Courtesy of the Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames

Commentarii secundo aucti, in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis, Anazarbei de medica materia (1560)

1560

1st published image of a fungus where it is possible to identify the genus

Plate: Agaricum [woodcut]

Mattioli, Pietro Andrea, 1500-1577.

Commentarii secundo aucti, in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis, Anazarbei de medica materia : adiectis quamplurimis plantarum, & animalium imaginibus, quæ in priore editione non habentur...

[Venetiis : in officina Valgrisiana, 1554, 1560 printing.]

Image Courtesy of the Library of the Arnold Arboretum

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1500-1577), an Italian physician and herbalist, served as the personal physician to Emperor Maximilian of Austria. In his herbal Commentarii in libros sex Pedacii Discoridis... (1560) he published the first fungi illustrations that can be identified with confidence, that of Agaricum as well as an illustration of black and white truffles.

Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1500-1577), an Italian physician and herbalist, served as the personal physician to Emperor Maximilian of Austria. In his herbal Commentarii in libros sex Pedacii Discoridis... (1560) he published the first fungi illustrations that can be identified with confidence, that of Agaricum as well as an illustration of black and white truffles.

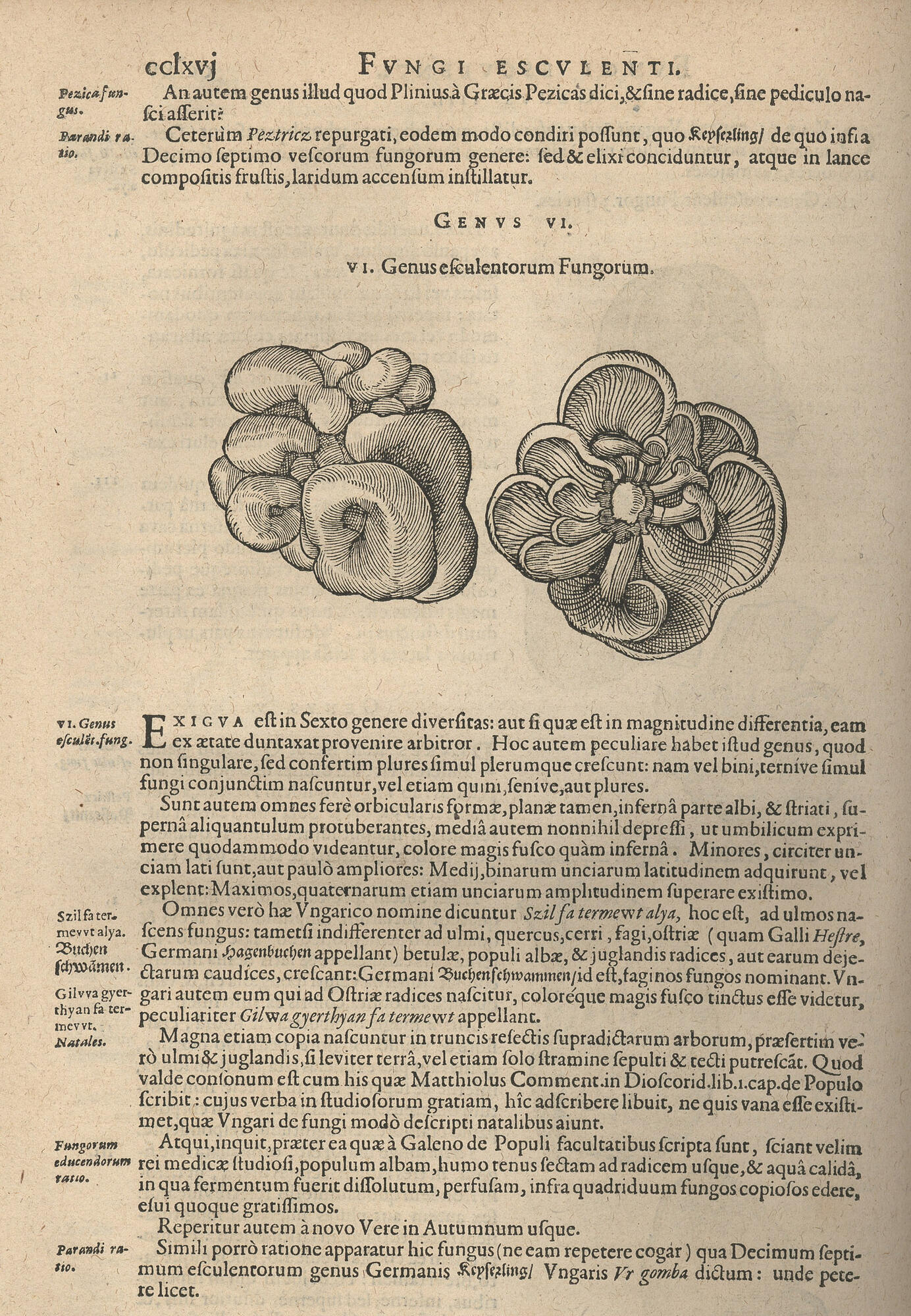

Rariorum plantarum historia (1601)

1601

1st full monograph written on fungi

Plate: Plate: Genus VI - efculentorum Fungorum [woodcut]

Clusius, Carolinus, 1526-1609.

Rariorum plantarum historia. Quae accesserint, proxima pagina docebit.

[Antwerpiae : Ex Officina Plantiniana, apud Joannem Moretum, 1601.]

Image Courtesy of the Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames

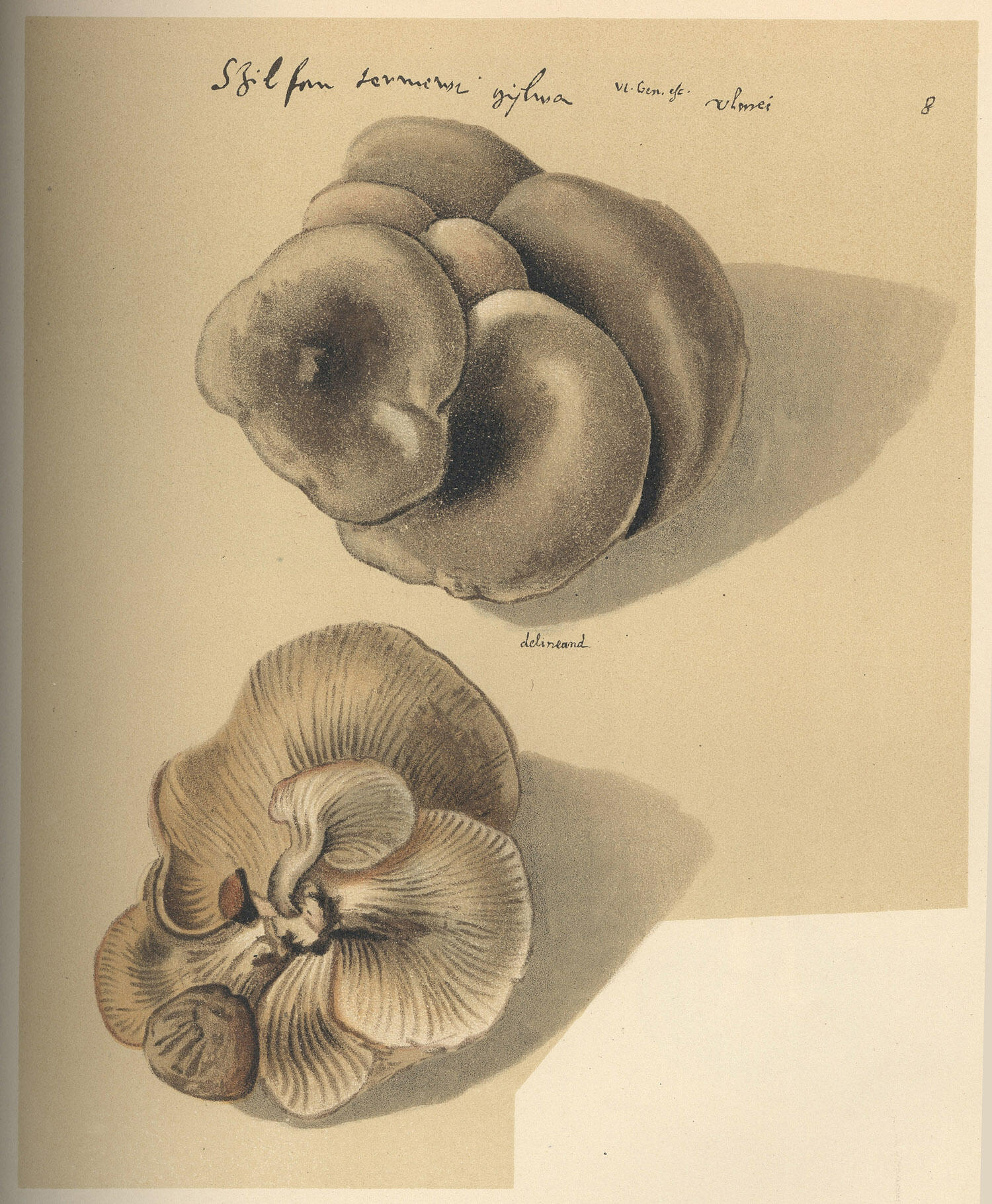

Original watercolors commission by Clusius that were to be published with his his monograph Fungorum. Plate: Genus VI - efculentorum Fungorum [watercolor]

Original watercolors commission by Clusius that were to be published with his his monograph Fungorum. Plate: Genus VI - efculentorum Fungorum [watercolor]

Clusius, Carolinus, 1526-1609.

These watercolors were misplaced by the printer and were not published until 1900 in:

Istvánffi, Gyula, 1860-1930.

Études et commentaires sur le Code de l'Escluse augmentés de quelques notices biographiques. [Budapest, L'auteur, 1900.] Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Jules-Charles l'Escluse [Latinized as Carolus Clusius] (1526-1609) was born in Arras (Province of Artois, Northern France) on 19 February 1526. His father was a nobleman who served as councilor at the provincial court of Artois. He studied at Montpellier with the botanist Guillaume Rondelet. During his formative years he acquired no less than eight languages and an extensive knowledge of a wide variety of subjects.

Jules-Charles l'Escluse [Latinized as Carolus Clusius] (1526-1609) was born in Arras (Province of Artois, Northern France) on 19 February 1526. His father was a nobleman who served as councilor at the provincial court of Artois. He studied at Montpellier with the botanist Guillaume Rondelet. During his formative years he acquired no less than eight languages and an extensive knowledge of a wide variety of subjects.

His first publication was a French translation of Rembert Dodoens' herbal, published in Antwerp in 1557. Having finished his studies, Clusius worked in various places and occupations. In 1573, after short stays in Paris and London, he was invited to Vienna by Emperor Maximilian II to serve as court physician and overseer of the imperial garden. Sadly because of his religious opinions he soon fell out of favor at court. In 1576 his Spanish flora (Rariorum aliquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia) was published by Christopher Plantin at Antwerp, followed in 1583 by his description of the plants of Austria and neighbouring regions (Rariorum aliquot stirpium, per Pannoniam, Austriam, & icinas quasdam provincia)

In 1593 Clusius was finally awarded a professorship of botany at the University of Leiden in 1593, a chair which he occupied until his death. In the last years at the University of Leiden Clusius published Rariorum plantarum historia (1601). This was his magnum opus, a re-edited version of his earlier works concluding with a previously unpublished section on fungi. Clusius died on the 4 April 1609 and was buried in the Vrouwekerk in Leiden.

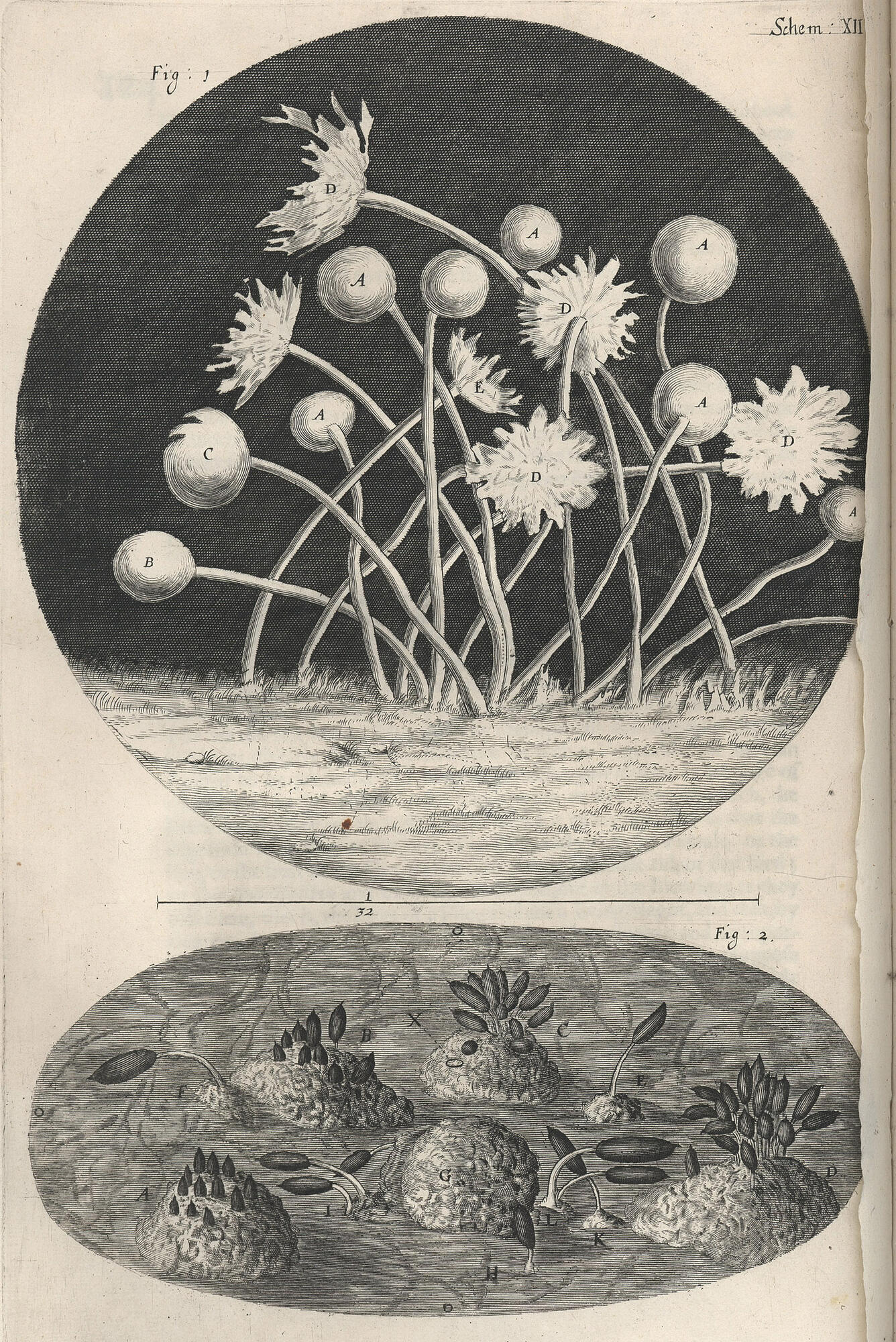

Micrographia (1665)

1665

1st illustration of microfungi and the 1st account of the internal structure of mushrooms

Figure 12 Microfungi [woodcut]

Hooke, Robert, 1635-1703.

Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasse: with observations and inquiries thereupon.

[London : Printed by Jo.Martyn, and Ja.Allestry, M DC LX V (1665).]

Image Courtesy of the Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames

Robert Hooke (1635-1703) was born on 18 July 1635, at Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight. He was the son of a churchman and was apparently largely educated at home by his father. He entered Westminster School at the age of thirteen, and from there went to Oxford. Hooke was soon asked to serve as an assistant to the chemist Robert Boyle and, in 1662, he was named Curator of Experiments of the newly formed Royal Society of London.

Robert Hooke (1635-1703) was born on 18 July 1635, at Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight. He was the son of a churchman and was apparently largely educated at home by his father. He entered Westminster School at the age of thirteen, and from there went to Oxford. Hooke was soon asked to serve as an assistant to the chemist Robert Boyle and, in 1662, he was named Curator of Experiments of the newly formed Royal Society of London.

Hooke's reputation in the history of biology largely rests on his book Micrographia, published in 1665. Hooke devised the compound microscope and illumination system, and with it he observed diverse organisms and gave the first account of the internal structure of mushrooms. Micrographia was an accurate and detailed record of his observations, illustrated with clear and detailed wood block illustrations.

Hooke later became Gresham Professor of Geometry at Gresham College, London, where he lived for the rest of his life. His health deteriorated over the last decade of his life, and he passed away in London on 3 March 1703.

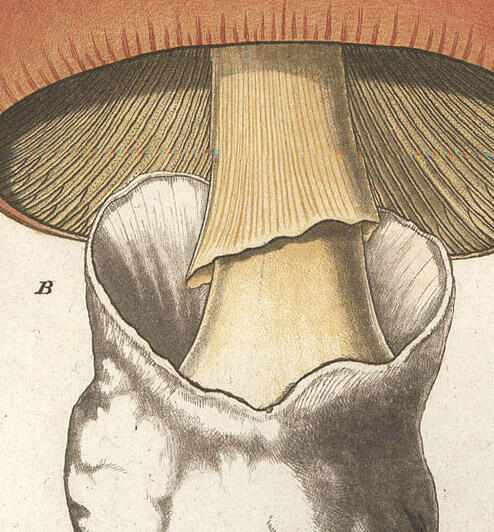

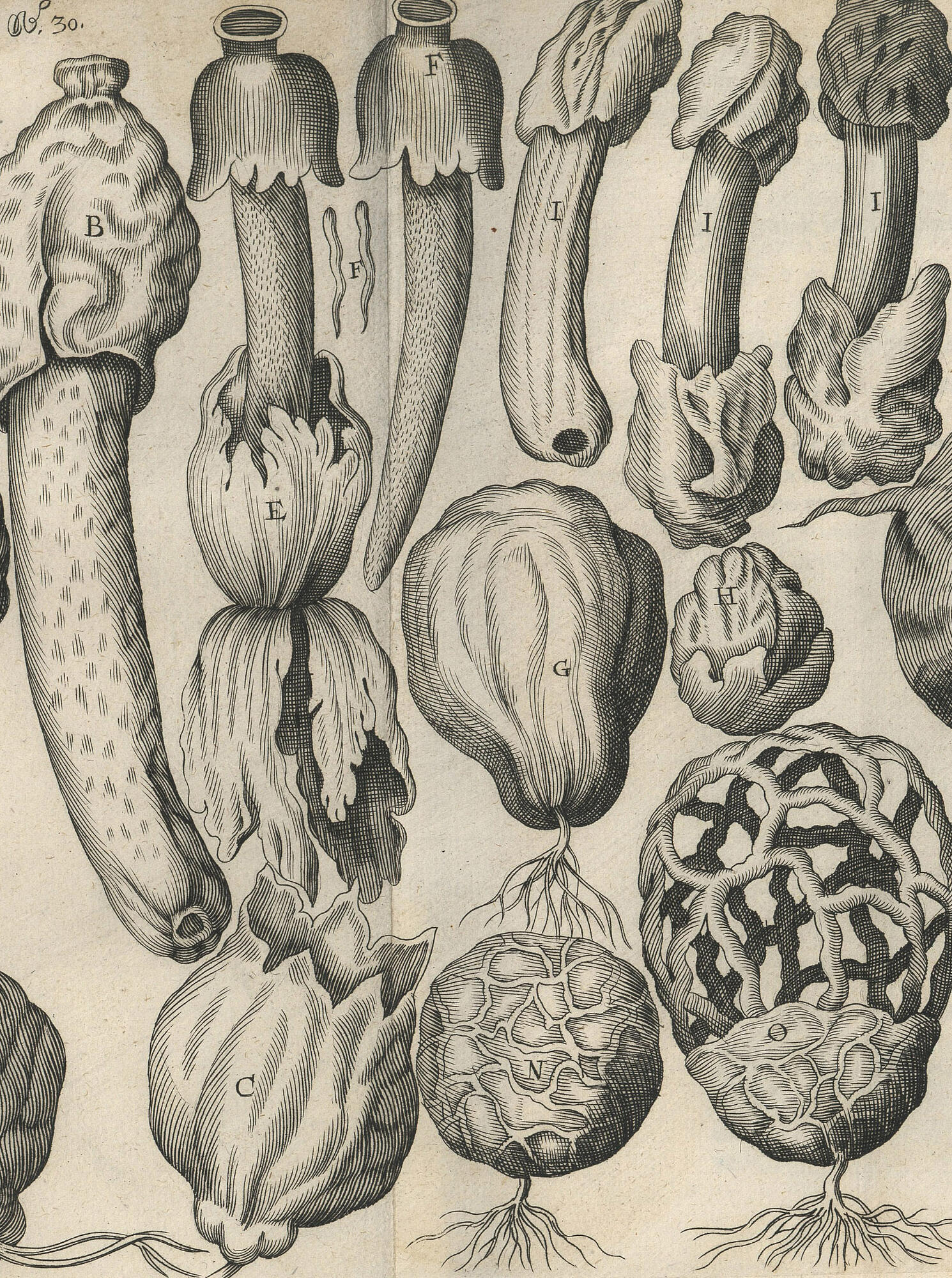

Theatrum fungorum oft het Tooneel der Campernoelien (1675)

1675

1st copperplate engraving of fungi

No. 30 Phallus [copperplate engraving]

Sterbeeck, Franciscus van, 1631-1693.

Theatrum fungorum oft het Tooneel der Campernoelien.

[T'Antwerpen, By I. Iacobs, 1675.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Franciscus van Sterbeeck (1631-1693), a Flemish priest of noble extraction, was born and died in Antwerp where he lived for the greater part of his life. During the eight years following his ordination in 1655, he suffered chronic illness and turned his attention to botany. He had a particular interest in fungi and soon became a recognized expert on the subject. In 1672 Adriaan David, an amateur botanist himself, showed van Sterbeeck a copy of Clusius' Code de l'Escluse. This book truly interested him and he used the drawings within it as the basis for his work Theatre fungorum.

Franciscus van Sterbeeck (1631-1693), a Flemish priest of noble extraction, was born and died in Antwerp where he lived for the greater part of his life. During the eight years following his ordination in 1655, he suffered chronic illness and turned his attention to botany. He had a particular interest in fungi and soon became a recognized expert on the subject. In 1672 Adriaan David, an amateur botanist himself, showed van Sterbeeck a copy of Clusius' Code de l'Escluse. This book truly interested him and he used the drawings within it as the basis for his work Theatre fungorum.

Theatre fungorum was published in 1675. Of the 135 illustrations of hymenomycetes included in its pages it is estimated that 77 were taken from Clusius and another 14 from other contemporary botanists. While the plates may be in a large part copies of others work much of the text includes new information.

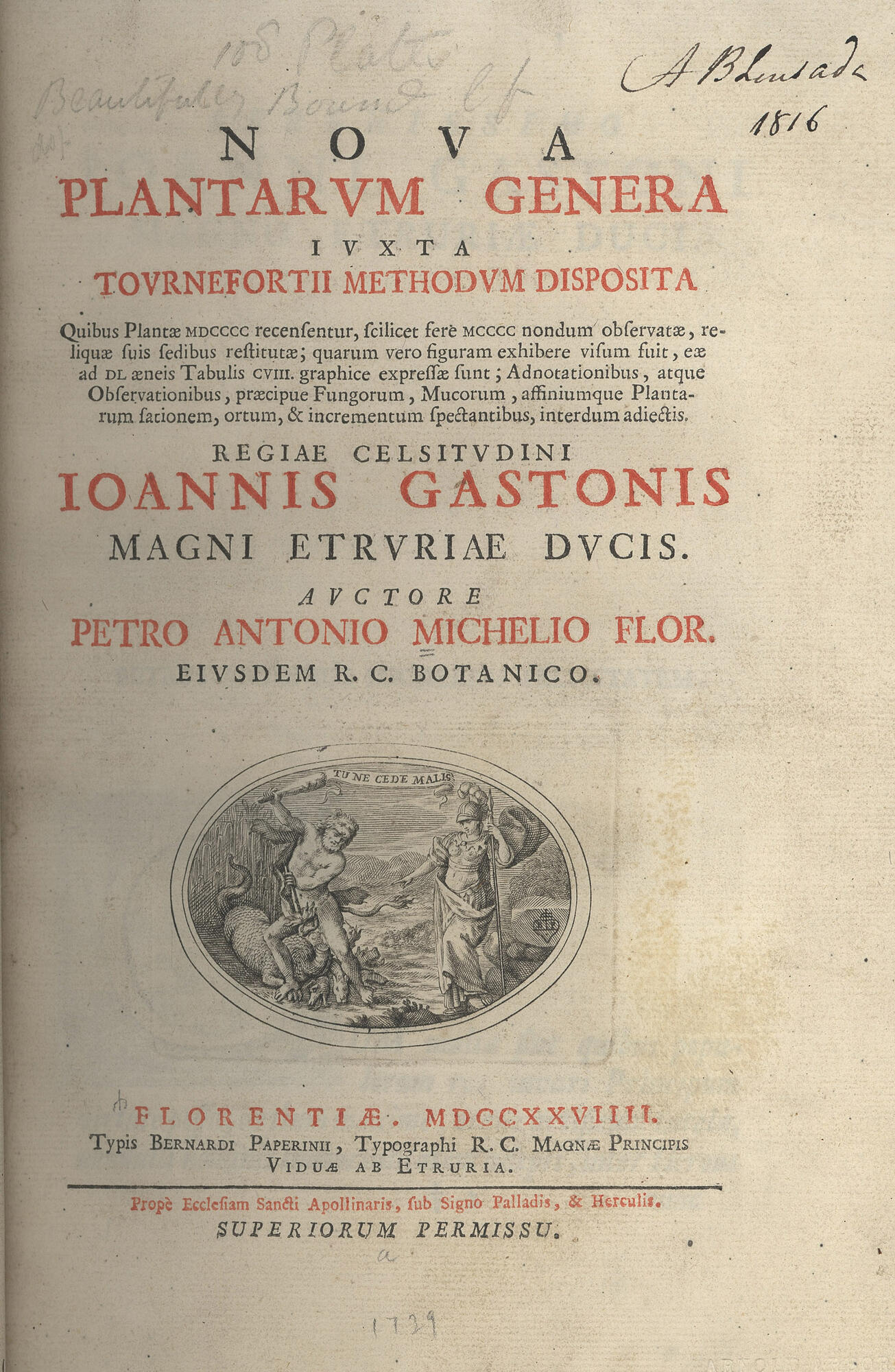

Noua plantarum genera (1729)

1729

Micheli was the first to point out that fungi definitely have reproductive bodies or spores.

Many believe this book marks the birth of mycology.

Table 86 Peziza and Helvella [copperplate engraving]

Micheli, Pier Antonio, 1679-1737.

Noua plantarum genera : iuxta Tournefortii methodum disposita quibus plantæ...

[Florentić. : Typis Bernardi Paperinii ..., MDCCXXVIIII 1729.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Pier Antonio Micheli (1679-1737) was born in Florence in 1679. As a young man he taught himself Latin and began to study plants. He was appointed botanist to Cosmo III, Duke of Tuscany, in 1706 and with this position came the responsibility of the public gardens of Florence. This position allowed him to continue his botanical studies. Micheli served also as a professor at the University of Pisa.

Pier Antonio Micheli (1679-1737) was born in Florence in 1679. As a young man he taught himself Latin and began to study plants. He was appointed botanist to Cosmo III, Duke of Tuscany, in 1706 and with this position came the responsibility of the public gardens of Florence. This position allowed him to continue his botanical studies. Micheli served also as a professor at the University of Pisa.

Micheli's Nova plantarum generum of 1729 revolutionized the study of fungus. In this work he included information on "the planting, origin and growth of fungi, mucors, and allied plants". He described 1900 plants, 1400 for the first time. Among these were 900 fungi and lichens, represented in no less than 73 plates. Micheli was also the first to observe spores in all groups of fungi, to describe asci, and to culture fungi from spores.

Micheli made a number of collecting trips around Europe and, on one such trip to Italy in 1736, he contracted pleurisy and died in Florence soon after.

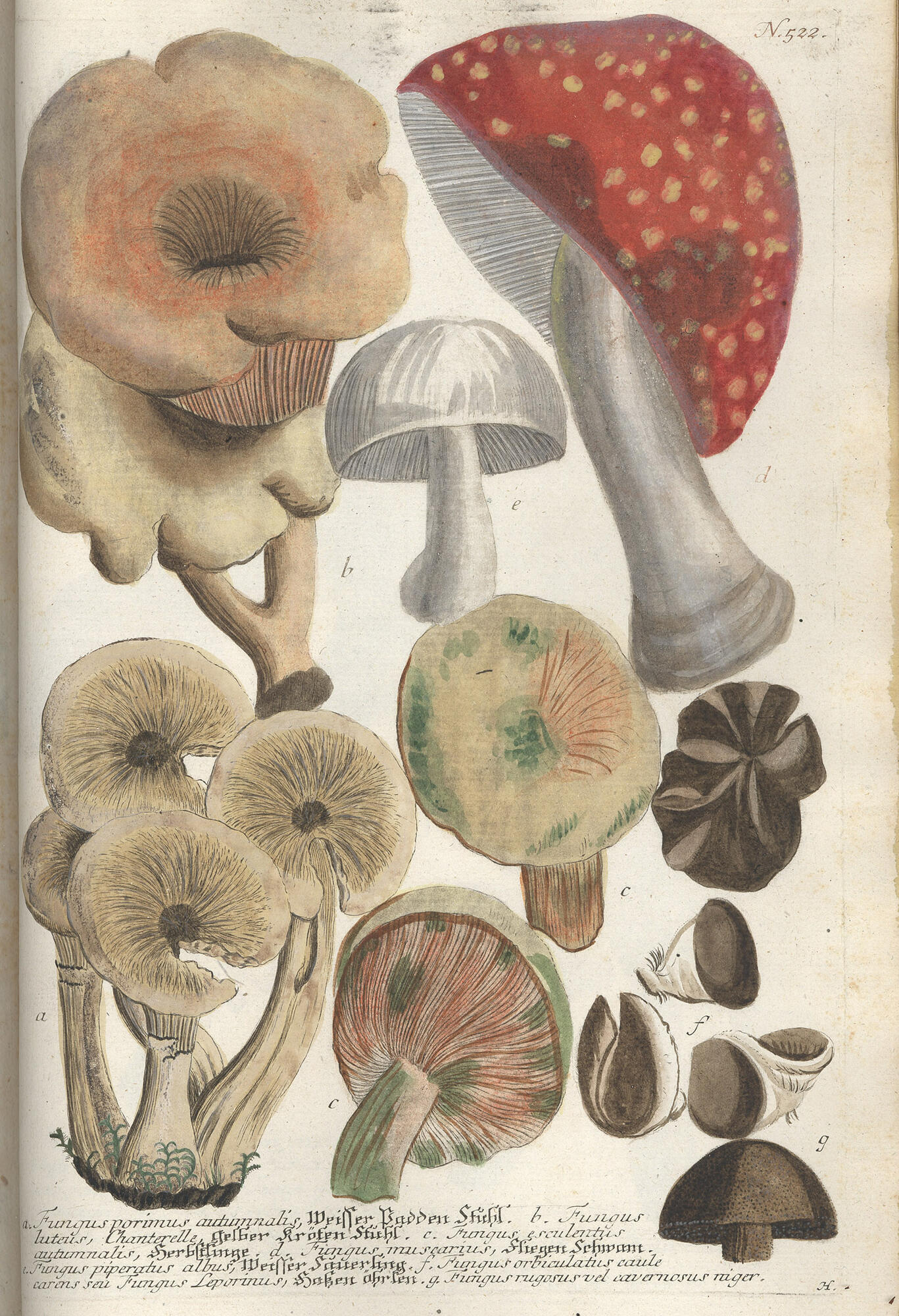

Phytanthoza Iconographia (1737)

1737

The first mycology publication to use color printed engraved plates.

No. 522 [copperplate engraving]

Weinmann, Johann Wilhelm 1683-1741.

Phytanthoza Iconographia

[Ratisbonae, 1737-1745]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Johann Wilhelm Weinmann (1683 - 1741) was born in Gardelegen, Germany on March 13, 1683. He settled in Regensburg in 1710 as a pharmacist's assistant and in 1712 was able to purchase his own apothecary shop. He flourished in his business affairs and this success allowed him to indulge in his great love for botany. He established a botanical garden in Regensburg published a Catalogus Alphabetico ordine exhibens Pharmaca in 1723.

Johann Wilhelm Weinmann (1683 - 1741) was born in Gardelegen, Germany on March 13, 1683. He settled in Regensburg in 1710 as a pharmacist's assistant and in 1712 was able to purchase his own apothecary shop. He flourished in his business affairs and this success allowed him to indulge in his great love for botany. He established a botanical garden in Regensburg published a Catalogus Alphabetico ordine exhibens Pharmaca in 1723.

In 1737-1745 Weinmann published Phytanthoza iconographia. His great work comprised eight folios with 1025 hand-colored engravings of several thousand plants. Among the artists employed to work on Phytanthoza was Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708-1770).

Unfortunately not all of Weinmann's illustrators were as familiar with botany as Ehret and the book suffered for their lack of knowledge. In The Art of Botanical Illustration (1994), Phytanthoza iconographia is described as more impressive in size than in quality.

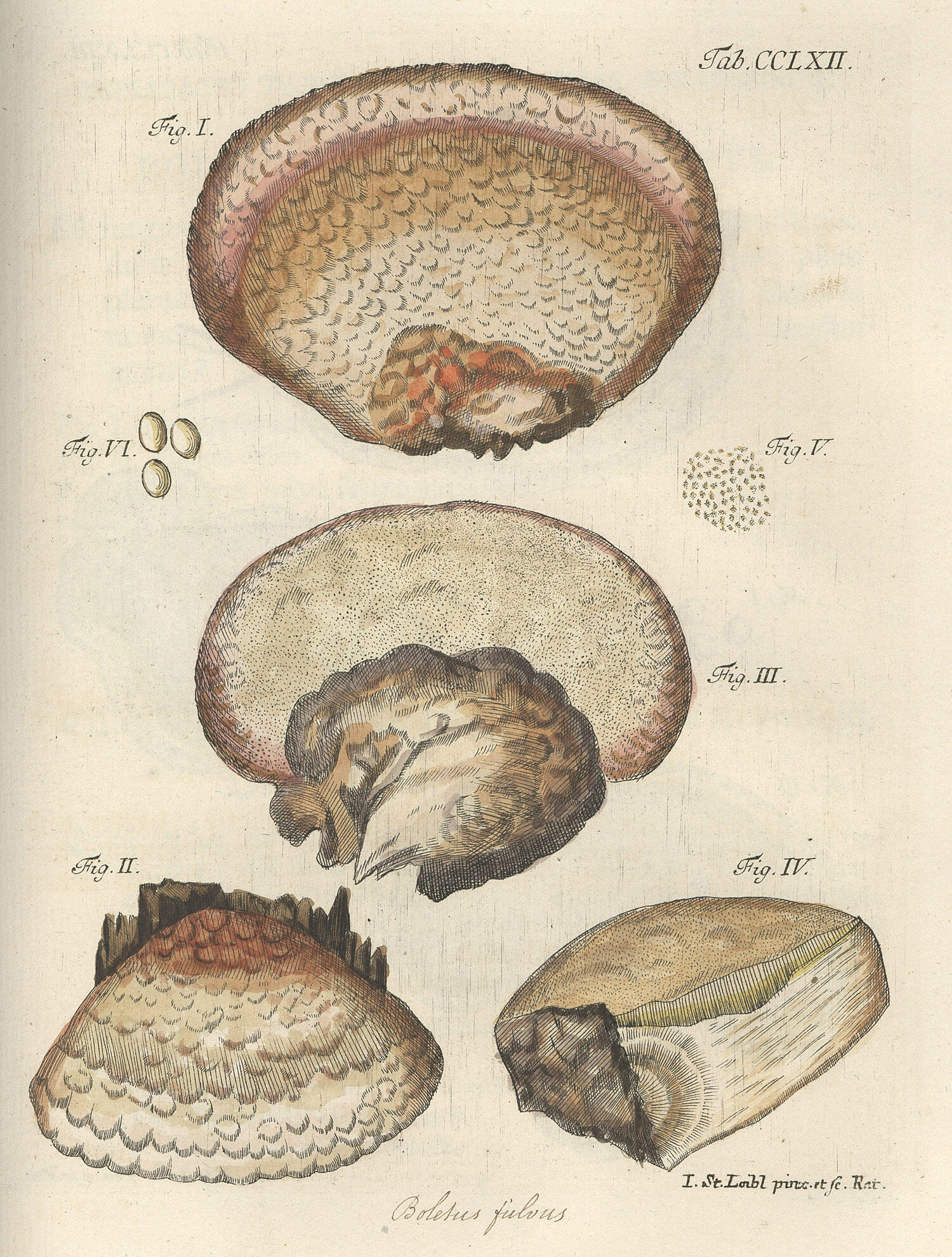

Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu circa Ratisbonam nascuntur icones (1762)

1762

One of the earliest books to use hand colored plates

Plate 262 Boletus filous [copperplate engraving]

Schäffer, Jacob Christian, 1718-1790.

Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu circa Ratisbonam nascuntur icones.

[1762-1774.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Jacob Christian Schäffer (1718-1790) is probably most well known for his research on alternative ways of paper-making. He studied at Halle and spent almost his whole working life in Regensburg, where he served as an evangelical clergyman.

Jacob Christian Schäffer (1718-1790) is probably most well known for his research on alternative ways of paper-making. He studied at Halle and spent almost his whole working life in Regensburg, where he served as an evangelical clergyman.

Schäffer was a man of many interests, he combined his theological studies with exhaustive studies of nature. His comprehensive book on mushrooms, Fungorum qui in Bavaria et Palatinatu..., was considered the standard work on the subject till well into the nineteenth century. Schäffer was the first to describe sterigmata in agaric, bolete, and clavaria and the first to use hand colored plates.

Histoire des champignons de la France (1780-1791)

1780-1791

This is the first book where the engraving itself was colored before printing.

Plate 72 Lycoperdon hyemale [copperplate engraving]

Bulliard, Pierre, 1752-1793.

Histoire des champignons de la France; ou, Traité élémentaire renfermant dans un ordre méthodique les descriptions et les figures des champignons qui croissent naturellement en France

[Paris, l'auteur, 1791.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Jean Baptiste Francois Bulliard, (1752-1793) [Pierre Bulliard] was born Aubepierre, France on 24 November 1752. He studied medicine in Langres, and in hospices in Clairvaux and Paris, where he set up his own practice. Bulliard began his botanical studies at the Abbey of Clairvaux and was a pupil of Jean Jacques Rousseau. He became one of the foremost French botanists of the eighteenth century.

Jean Baptiste Francois Bulliard, (1752-1793) [Pierre Bulliard] was born Aubepierre, France on 24 November 1752. He studied medicine in Langres, and in hospices in Clairvaux and Paris, where he set up his own practice. Bulliard began his botanical studies at the Abbey of Clairvaux and was a pupil of Jean Jacques Rousseau. He became one of the foremost French botanists of the eighteenth century.

In his Herbier de la France, one of the earliest examples of true color printing, Bulliard drew, engraved, mixed the inks, and color-printed more than 600 plates of flowers and fungi growing in France. Bulliard line-etched the oulines, veins, and linear shading in black for each plate. He then superimposed three tint plates, each engraved with the individual tones necessary to print separately the green, red and yellow of each image. His accuracy in lining up the plates and the delicacy and accuracy of his color printing, make this an outstanding example of eighteenth century botanical illustration.

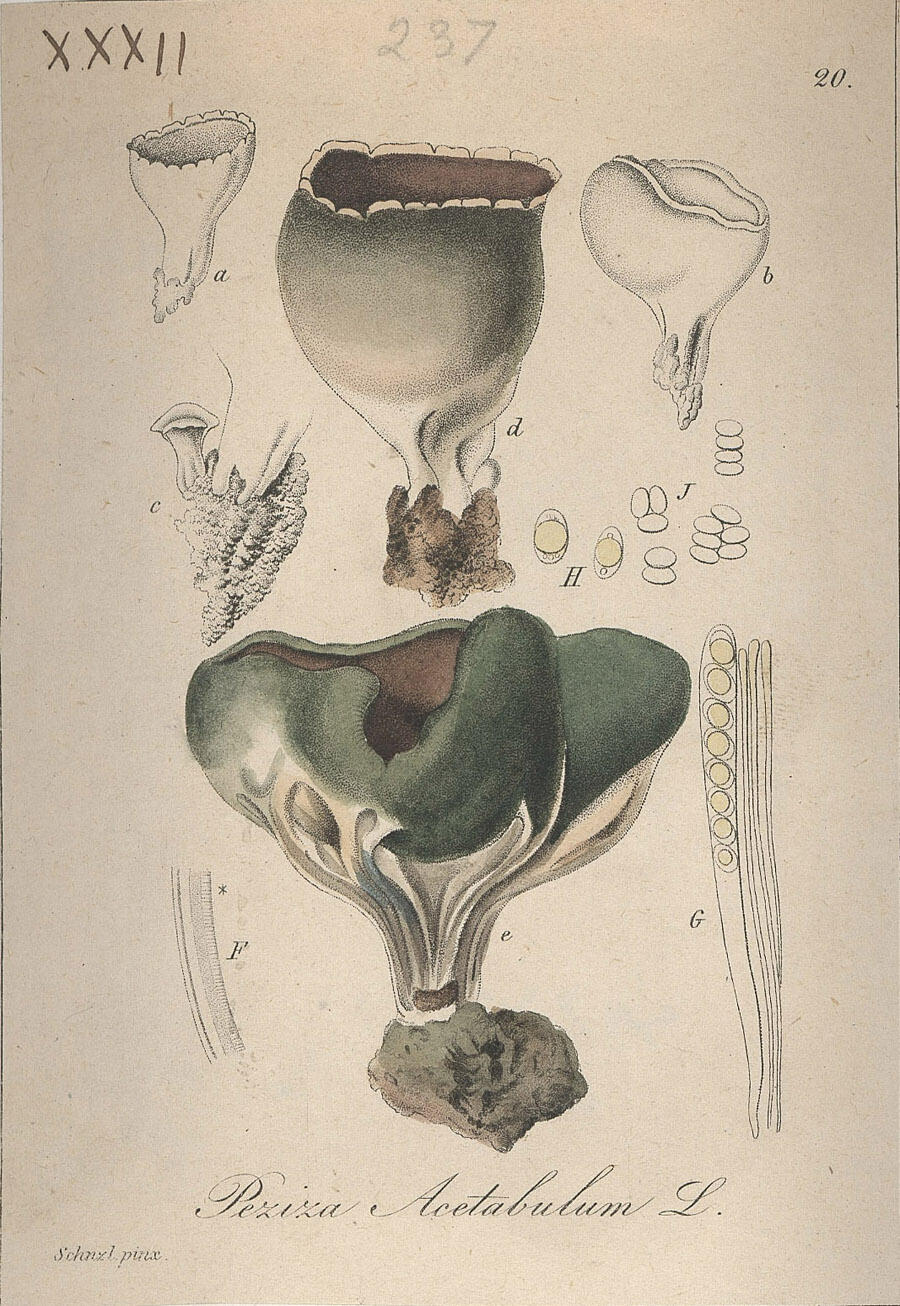

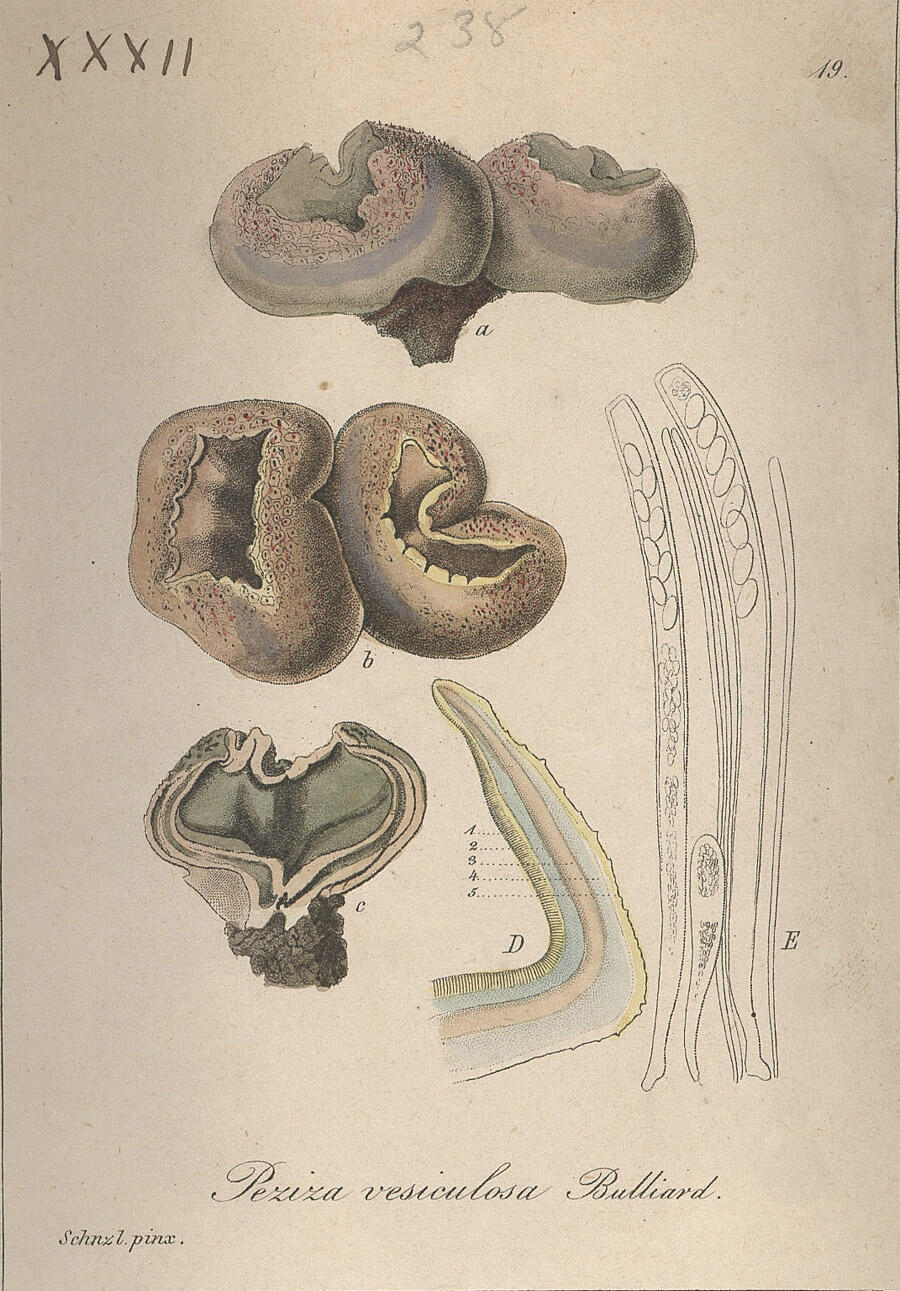

Deutschlands flora in abbildungen nach der natur mit beschreibungen (1801-1839)

1801-1839

An excellent example of colored copperplate printing.

Plate 16-20 Peziza [copperplate engraving]

Sturm, Jacob, 1771-1848.

Deutschlands flora in abbildungen nach der natur mit beschreibungen.

[Nürnberg, 1801-1839.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Jakob Sturm (1771-1848) was born in Nuremberg, Germany, the only son of engraver Johann Georg Sturm. He received only a modest formal education before entering his apprenticeship under his father, who trained him in the art of drawing and copperplate engraving.

Sturm is considered by some to be the most famous engraver of entomological and botanical publications in Germany at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. Many engravings of German flora existed already; but, as Sturm wrote in 1796, "some of them are badly drawn and coloured; some have been broken up and dispersed; some are only to be found in large and splendid publications which often even the lover of botany does not get a chance of seeing once in a lifetime."

Sturm's plates are very delicately drawn and depict the smallest details. They enjoyed a great popularity among naturalists. He deliberately chose a minute format in order to make a knowledge of the German flora available by pictures to as many as possible and as cheaply as possible.

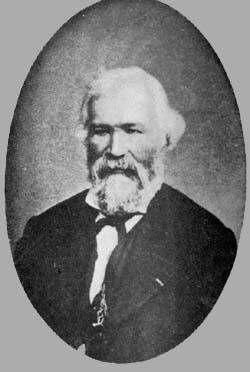

Synopsis fungorum Carolinae superioris secundum observationes ... (1821)

1821

The first plates of American fungi.

Table II Merulius, Boletus, Hydnum, Thelephora [copperplate engraving]

Schweinitz, Lewis David von, 1780-1834.

Synopsis fungorum Carolinae superioris secundum observationes ...

[Ed. a D.F. Schwaegrichen ... n.p., 1822]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Lewis David von Schweinitz (1780-1834) was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania on 13 February 1780. He was educated by the Moravian Brethren and at eighteen he entered a theological seminary in Germany. Upon graduation he became a teacher in the Moravian academy of Niesky, Silesia and was ordained deacon in 1808. In 1812 he returned to the United States and assumed a position as a church administrator in Salem, North Carolina.

Lewis David von Schweinitz (1780-1834) was born in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania on 13 February 1780. He was educated by the Moravian Brethren and at eighteen he entered a theological seminary in Germany. Upon graduation he became a teacher in the Moravian academy of Niesky, Silesia and was ordained deacon in 1808. In 1812 he returned to the United States and assumed a position as a church administrator in Salem, North Carolina.

Though his clerical vocation was his life's work, Schweinitz developed a parallel career in botany and mycology. He collected fungi in the eastern states and collaborated with John Torrey, Johannes Baptista von Albertini, and Prince Maximillian II of Weid among many others. His Synopsis Fungorum Carolinae Superioris (1822) and Synopsis Fungorum in America Borealis (1832) are landmark studies in the history of mycology. In his 1832 work alone, he described over 3,000 species of fungi, more than half of which were species new to science.

Schweinitz was also an accomplished illustrator and created watercolor prints and drawings of botanical subjects that supplemented his descriptive work. Lewis David von Schweinitz died in 1834 with an unfinished work in progress.

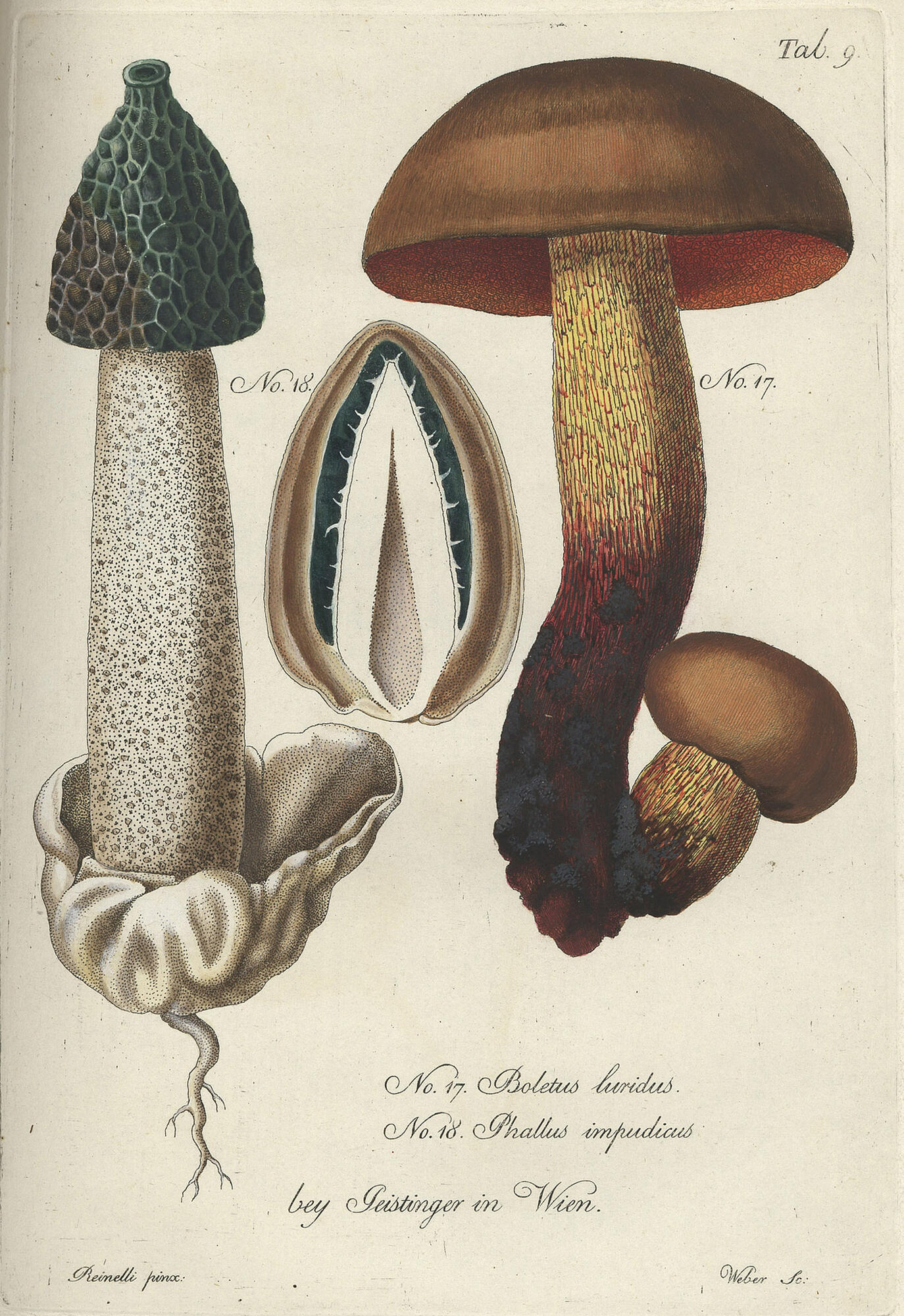

Fungi austriaci delectu singulari iconibus... (1830)

1830

These plates were hand colored and issued with a series of wax models. Trattnick was also the first to use the term "mycelium".

Table 9: Boletus luridus and Phallus impudens [copperplate engraving]

Trattinnick, Leopold, 1764-1849.

Fungi austriaci delectu singulari iconibus XL observationibusque illustrati auctore Leopoldo Trattinnick.

[Wien, C. Gerold, 1830.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

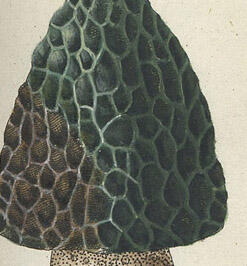

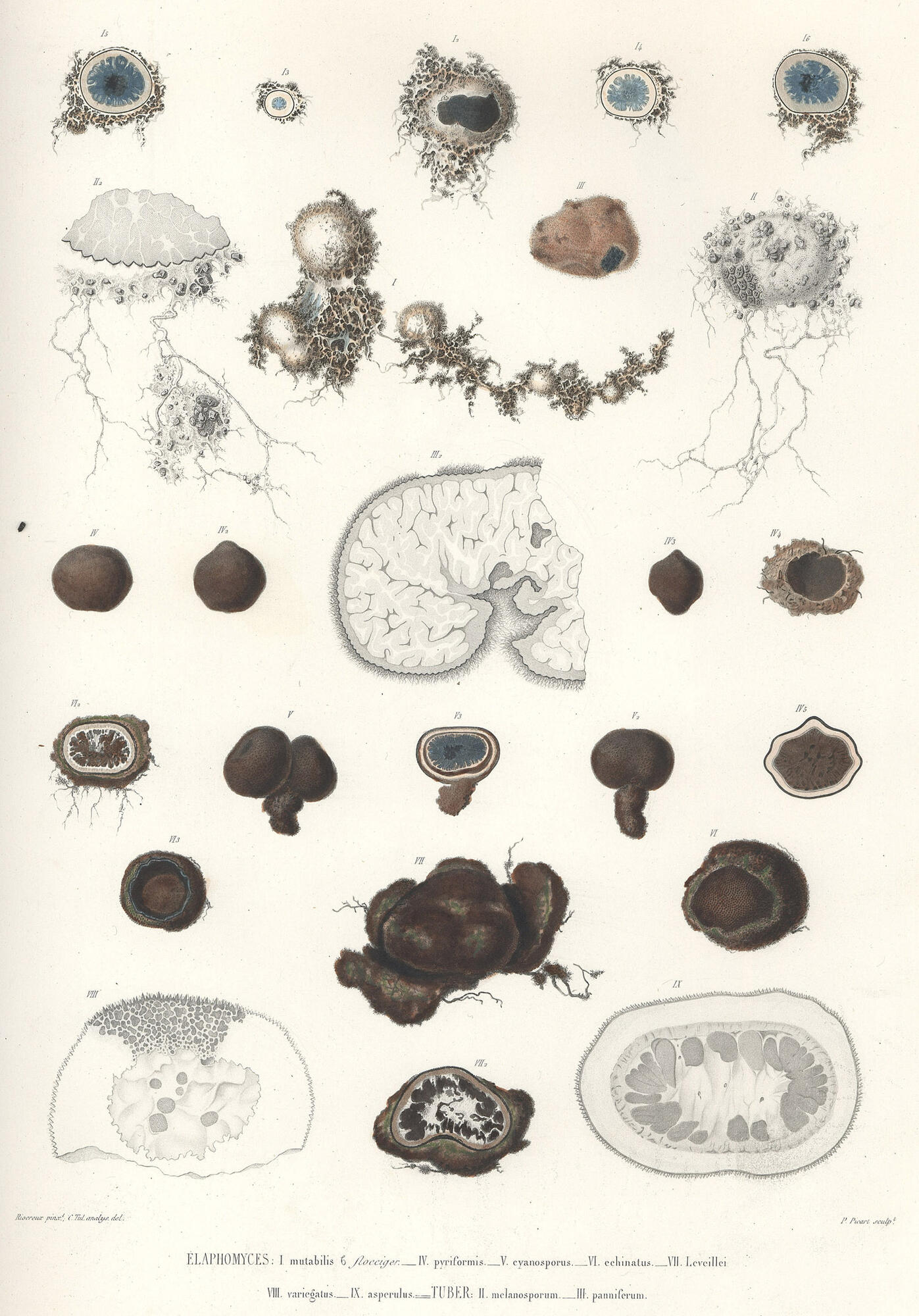

Fungi hypogæi (1851)

1851

Mycological illustrators now began to show the inner workings of the fungi.

Plate: Elaphomyces [copperplate engraving]

Tulasne, Louis René, 1815-1885.

Fungi hypogæi. Histoire et monographie des champignons hypogés ...

[Parisiis, apud F. Klincksieck, 1851.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Louis René Tulasne (1815-1885) was born in Azay-le-Rideau, France, 12 September 1815. He studied law at Poitiers, but later turned his attention to botany and worked until 1842 in company with Auguste de Saint-Hilaire on the flora of Brazil. He was an assistant naturalist at the Museum of Natural History at Paris 1842-72; after this he retired from active work. In 1845 he was elected a member of the Academy to succeed Adrian de Jussieu.

Louis René Tulasne (1815-1885) was born in Azay-le-Rideau, France, 12 September 1815. He studied law at Poitiers, but later turned his attention to botany and worked until 1842 in company with Auguste de Saint-Hilaire on the flora of Brazil. He was an assistant naturalist at the Museum of Natural History at Paris 1842-72; after this he retired from active work. In 1845 he was elected a member of the Academy to succeed Adrian de Jussieu.

Tulasne published numerous botanical works, the first appearing in 1845; he first wrote on the phanerogamia, as for instance, on the leguminosæ of South America, then on the cryptogamia, and especially on the fungi. He gained a world-wide reputation by his microscopic study of fungi, especially by his investigation of the small parasitic fungi. His research threw much light on the obscure and complicated history of their evolution. In this science he worked in collaboration with his brother Charles (1816-1885). The chief publications issued by the two brothers are: Fungi hypogæi (1851), and Selecta fungorum carpologia (1861-65), a work of the greatest importance for mycology, particularly on account of the splendid illustrations in the sixty-one plates.

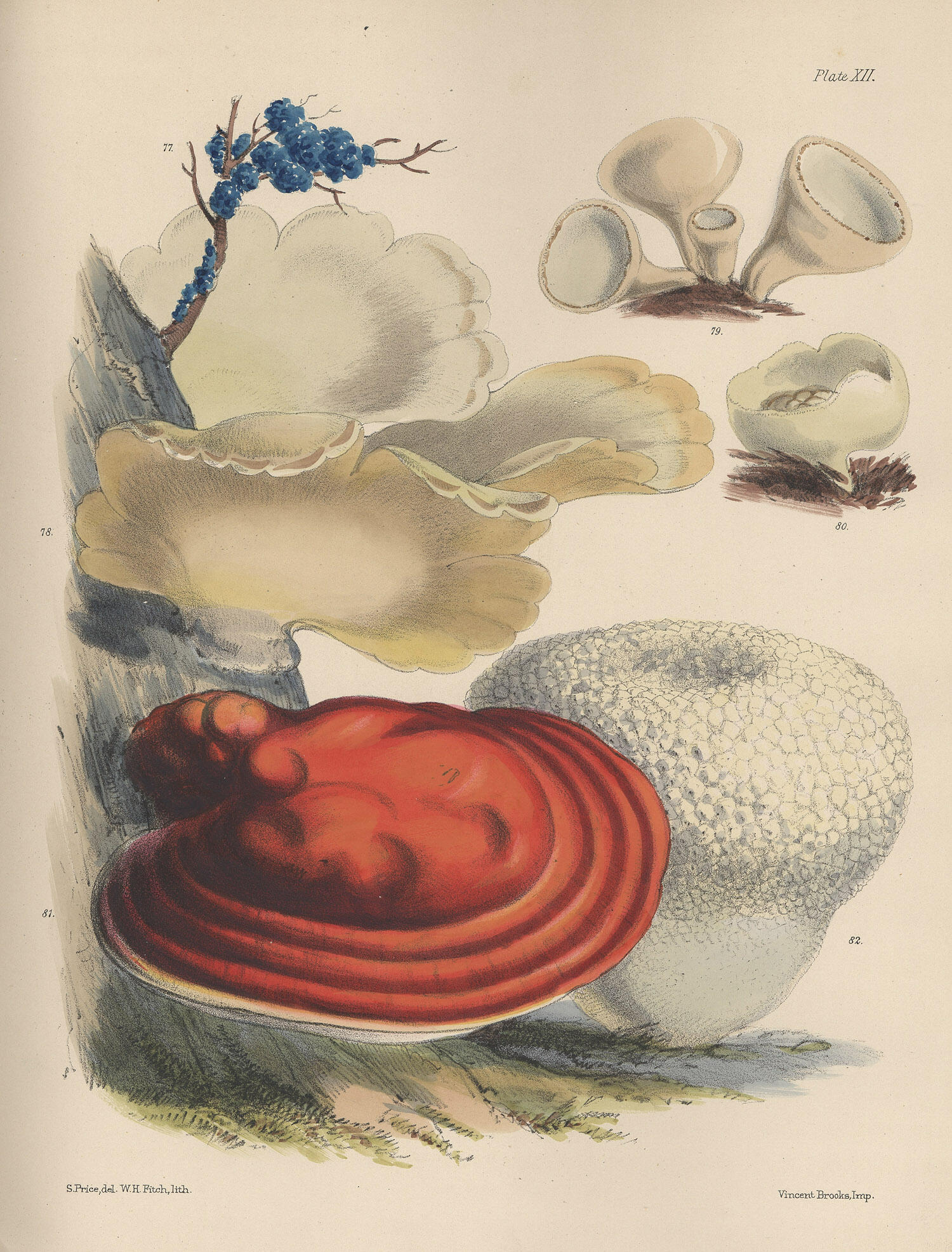

Illustrations of the fungi of our fields and woods (1860)

1860

An early mycological work printed using lithography.

Plate XII [lithography]

Price, Sarah.

Illustrations of the fungi of our fields and woods.

Drawn from natural specimens by Sarah Price.

[Published for the author by Lovell Reeve & Co., 5, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, 1864-65.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

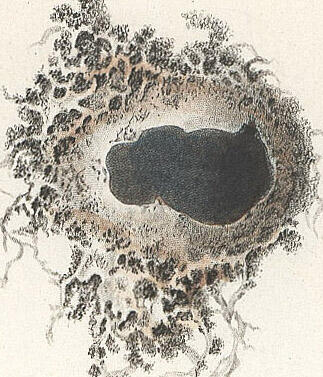

Gasteromycetes Hungariae (1904)

1904

An early example of tri-color printing.

Table VIII Geaster [tri-color printing]

Hollos, Laszlo, 1859-1940.

Gasteromycetes Hungariae: Die Gasteromyceten Ungarns...

[Leipzig: Oswald Weigel, 1904]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

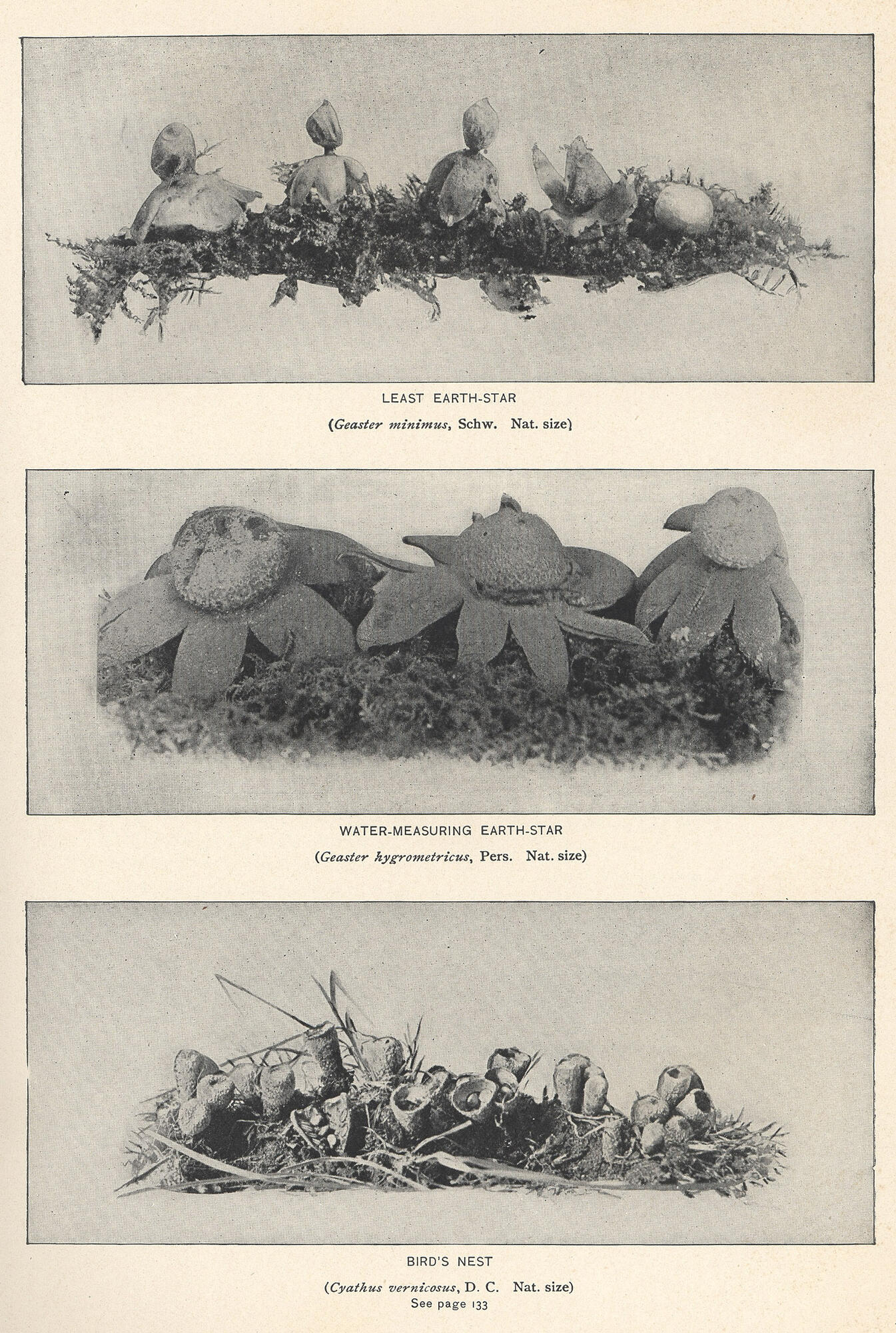

The mushroom book (1905)

1905

One of the earliest examples of photographs of fungi, both black & white and hand tinted, being used to illustrate a work.

Plates: Geaster & Clavarius [photography]

Marshall, Nina Lovering

The mushroom book. A popular guide to the identification and study of our commoner Fungi...

[Doubleday, 1905]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Icones mycologicæ (1905-1910)

1905-10

One of the finest examples of color printed lithography.

Plate 116 Cortinarius [lithography]

Boudier, Émile, 1828-1920.

Icones mycologicæ,

ou Iconographie des champignons de France

principalement Discomycetes avec texte descriptif

par Émile Boudier.

[Paris, P. Klincksieck, L. Lhomme, Successeur, 1905-10.]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

Jean Louis Émile Boudier (1828-1920) [Émile Boudier] was, according to C.G. Lloyd, "the acknowledged master of French mycology". He started off his career as a pharmacist and then, after 25 years, left this profession to pursue the study of mycology full time.

Jean Louis Émile Boudier (1828-1920) [Émile Boudier] was, according to C.G. Lloyd, "the acknowledged master of French mycology". He started off his career as a pharmacist and then, after 25 years, left this profession to pursue the study of mycology full time.

When his work Icones mycologicæ, ou Iconographie des champignons de France principalement Discomycetes was published in 1905 it was proclaimed to be the "acme of excellence".

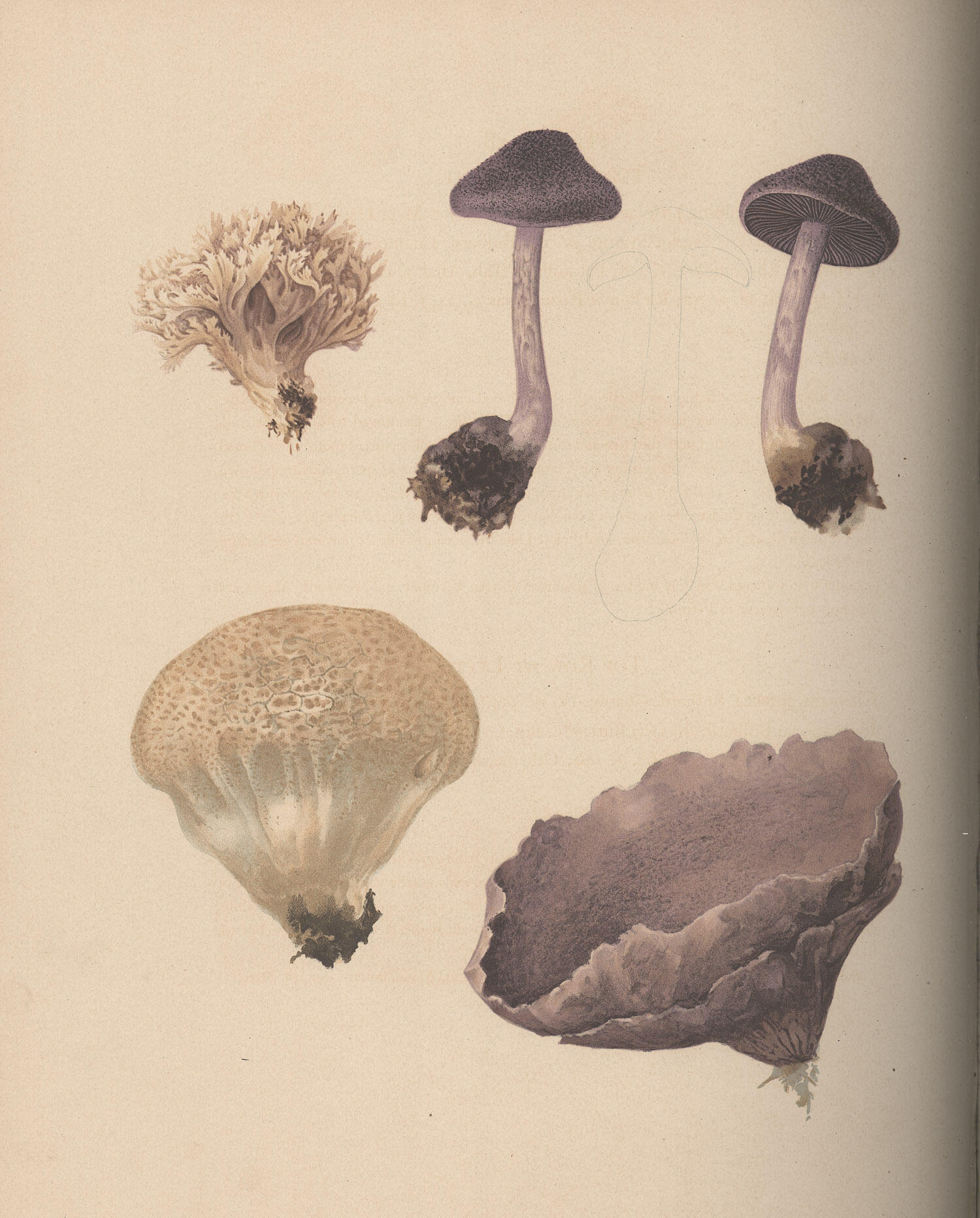

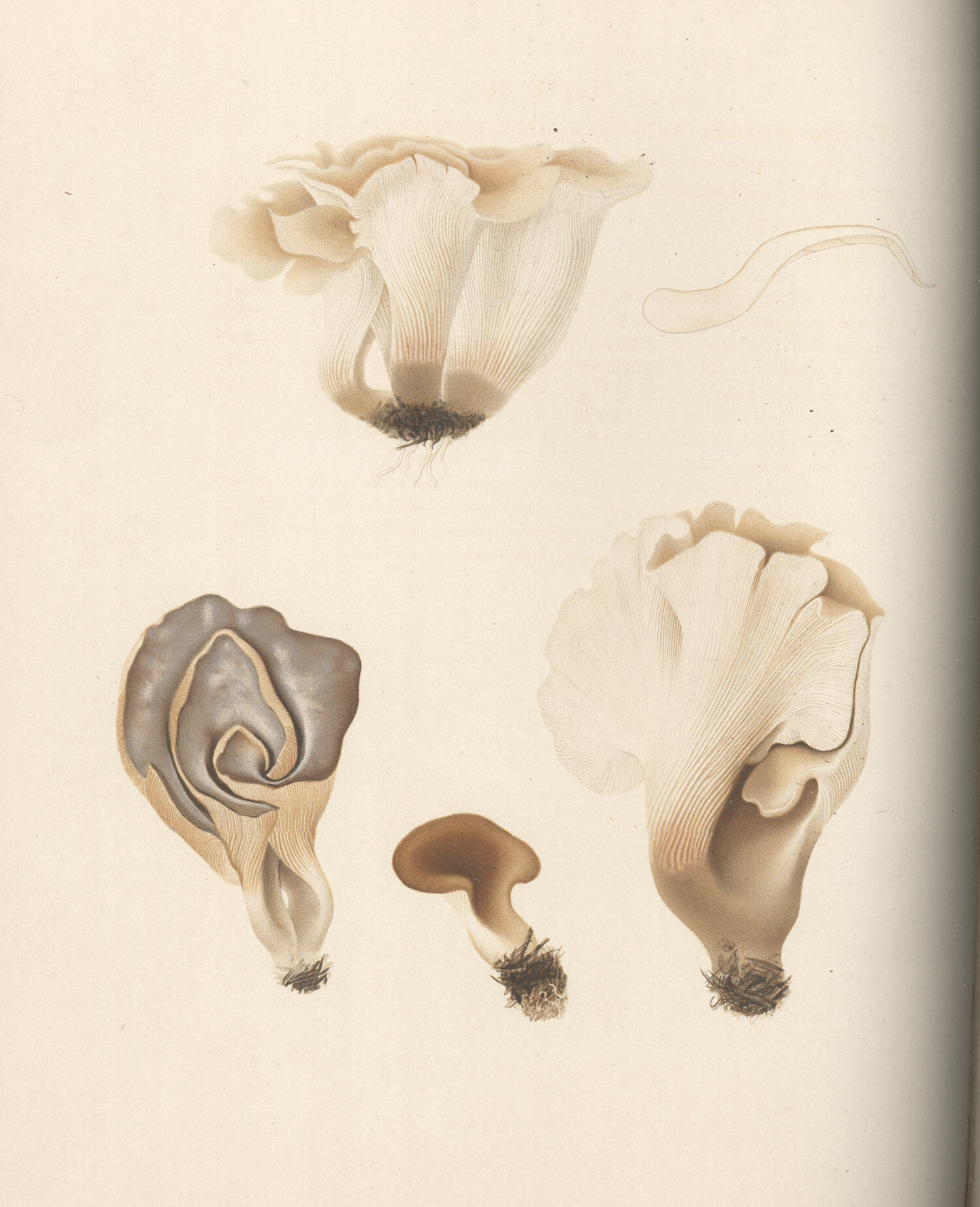

Icones Farlowianae (1929)

1929

Another excellent example of lithographic printing.

Plate: Plates 58 Cortinarious (Inoloma) violaceus

and Clavaria cinerea

and Plate 22 Plearotus petaloides [heliotype]

Farlow, W. G. (William Gilson), 1844-1919.

Icones Farlowianae : illustrations of the larger Fungi of eastern North America

[ Cambridge, Mass. : The Farlow Library and Herbarium of Harvard University, 1929 (Boston : Merrymount Press)]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany

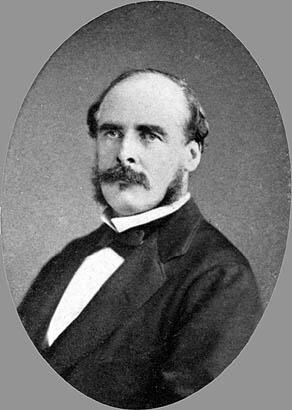

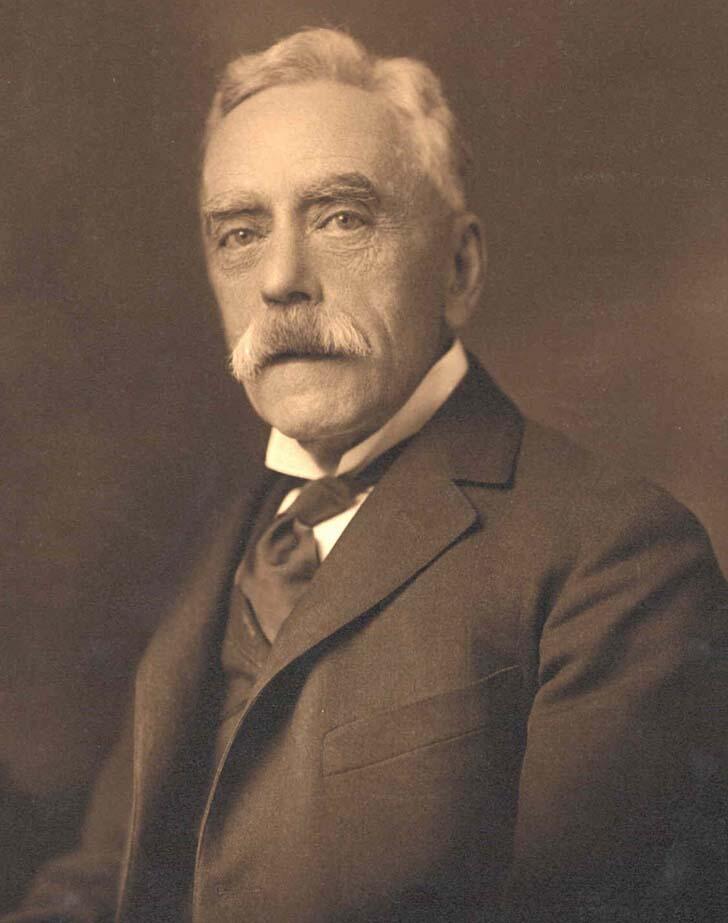

William Gilson Farlow was born near Boston, Massachusetts on December 17, 1844. He received his M.D. from Harvard in May of 1870. In July of the same year Farlow was hired to assist Asa Gray, Fisher Professor of Natural History, a position he held for two years.

William Gilson Farlow was born near Boston, Massachusetts on December 17, 1844. He received his M.D. from Harvard in May of 1870. In July of the same year Farlow was hired to assist Asa Gray, Fisher Professor of Natural History, a position he held for two years.

In 1872 he traveled to Europe, where he studied for two years with Anton de Bary as well as other prominent botanists in Germany, France and Scandinavia. When he returned in 1874 he was made Assistant Professor of Botany at the Bussey Institution of Harvard University. In 1879 Farlow was appointed Professor of Cryptogamic Botany at Harvard. He remained in this position for the rest of his life and continued to advise doctoral candidates even after his retirement from active teaching in 1896.

Farlow's contributions to botany were acknowledged internationally. At least two genera and many species have been named for Farlow. He will be remembered as a pioneer investigator in plant pathology, who helped establish a systematic nomenclature for fungi, and inspired and directed some of America's leading botanists. It was said that "His firsthand knowledge of cryptograms was greater than that of any botanist and he was probably the most learned man in his profession".

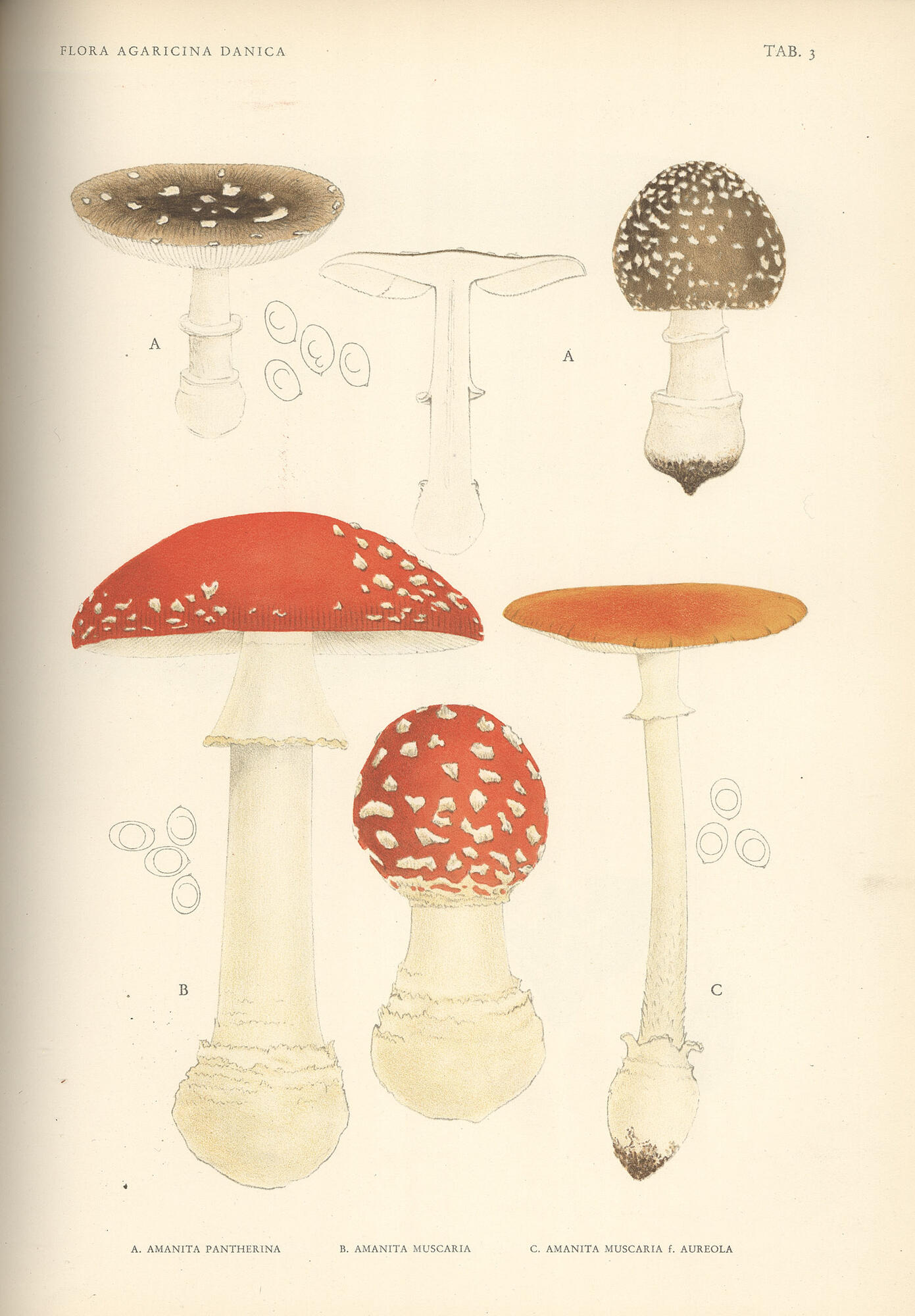

Flora Agaricina Danica (1935-1940)

1935-1940

An early example of collotype printing.

Plate I [collotype]

Lange, Jakob E., 1864-1941

Flora Agaricina Danica

[Copenhagen: Recato a/s, 1935-40]

Image Courtesy of the Farlow Library of Cryptogamic Botany