Biography

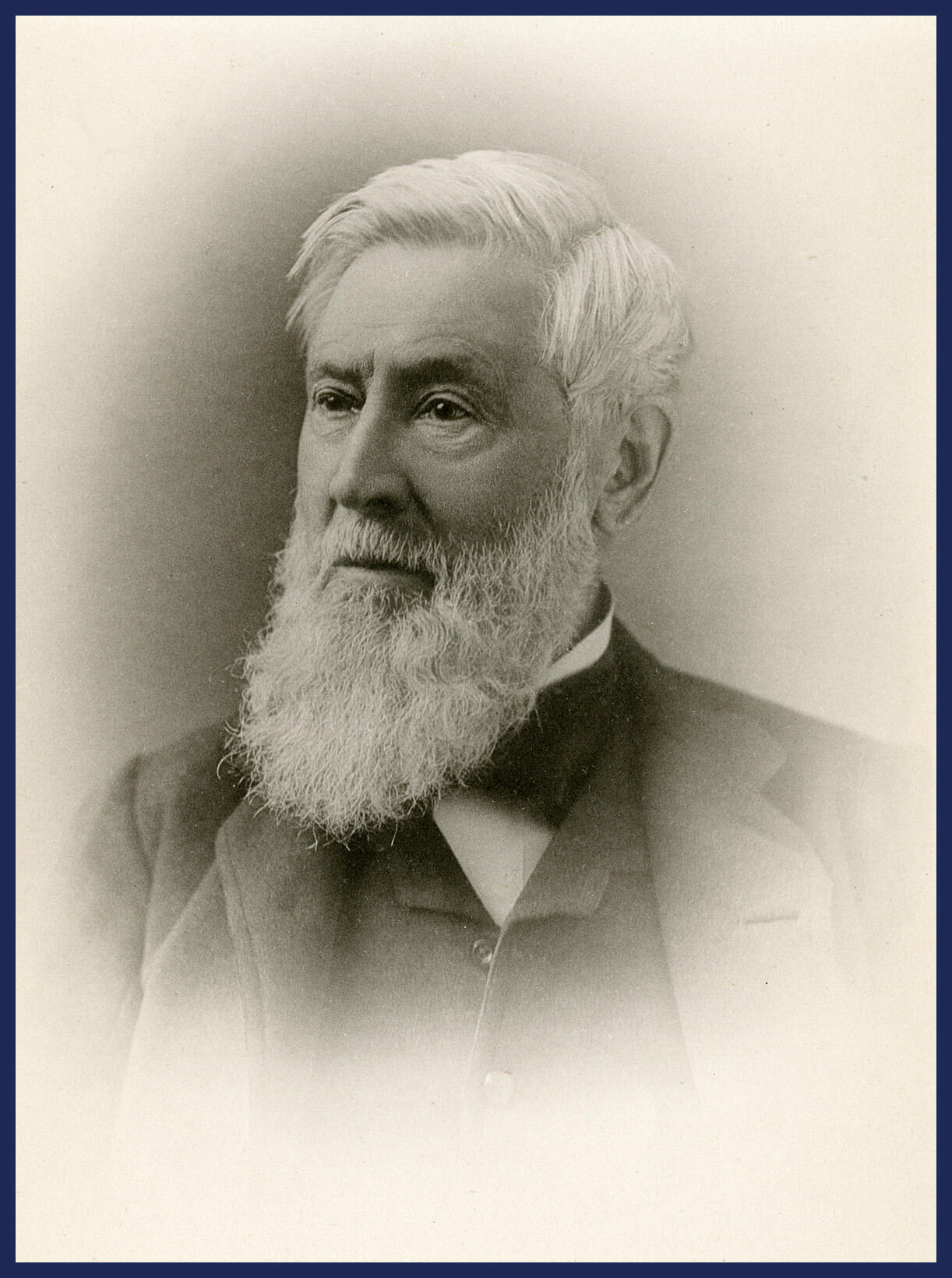

Asa Gray

by Walter Deane

The Bulletin Of The Torrey Botanical Club

2 March 1888, vol. XV, no. 3

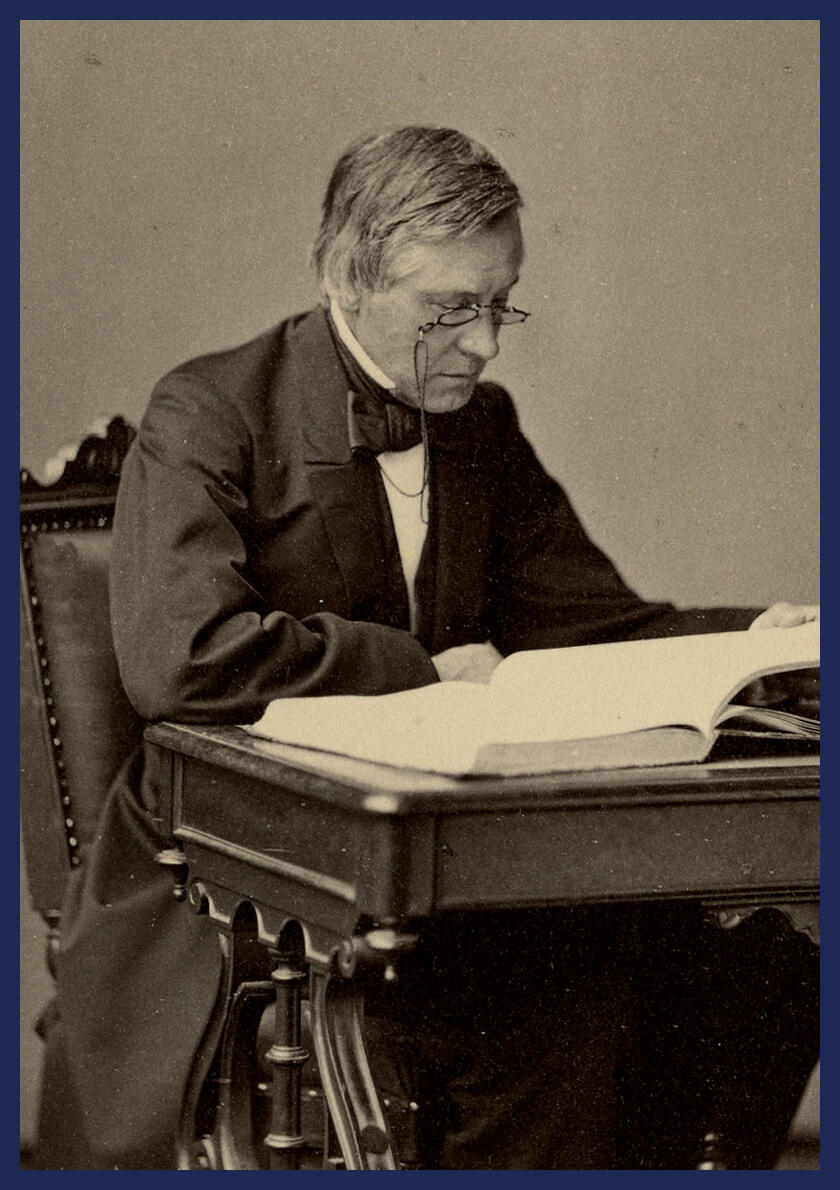

Asa Gray died in Cambridge, Mass., on the 30th of January, 1888. The world has lost a most distinguished botanist, and all, who knew him, a cherished friend. No words are needed to sound his praises, and he himself would not have desired it. His early life was spent in the State of New York, where his love for botany was first developed. Born in Paris, Oneida Co., N. Y., one of his earliest occupations was to feed the bark-mill and drive the horse at his father's tannery. He attended the Clinton Grammar School and from there went to Fairfield Academy, entering later the Medical College of the Western District of Fairfield; and, though he graduated with the degree of M.D. in 1831, yet he never practiced medicine.

Asa Gray died in Cambridge, Mass., on the 30th of January, 1888. The world has lost a most distinguished botanist, and all, who knew him, a cherished friend. No words are needed to sound his praises, and he himself would not have desired it. His early life was spent in the State of New York, where his love for botany was first developed. Born in Paris, Oneida Co., N. Y., one of his earliest occupations was to feed the bark-mill and drive the horse at his father's tannery. He attended the Clinton Grammar School and from there went to Fairfield Academy, entering later the Medical College of the Western District of Fairfield; and, though he graduated with the degree of M.D. in 1831, yet he never practiced medicine.

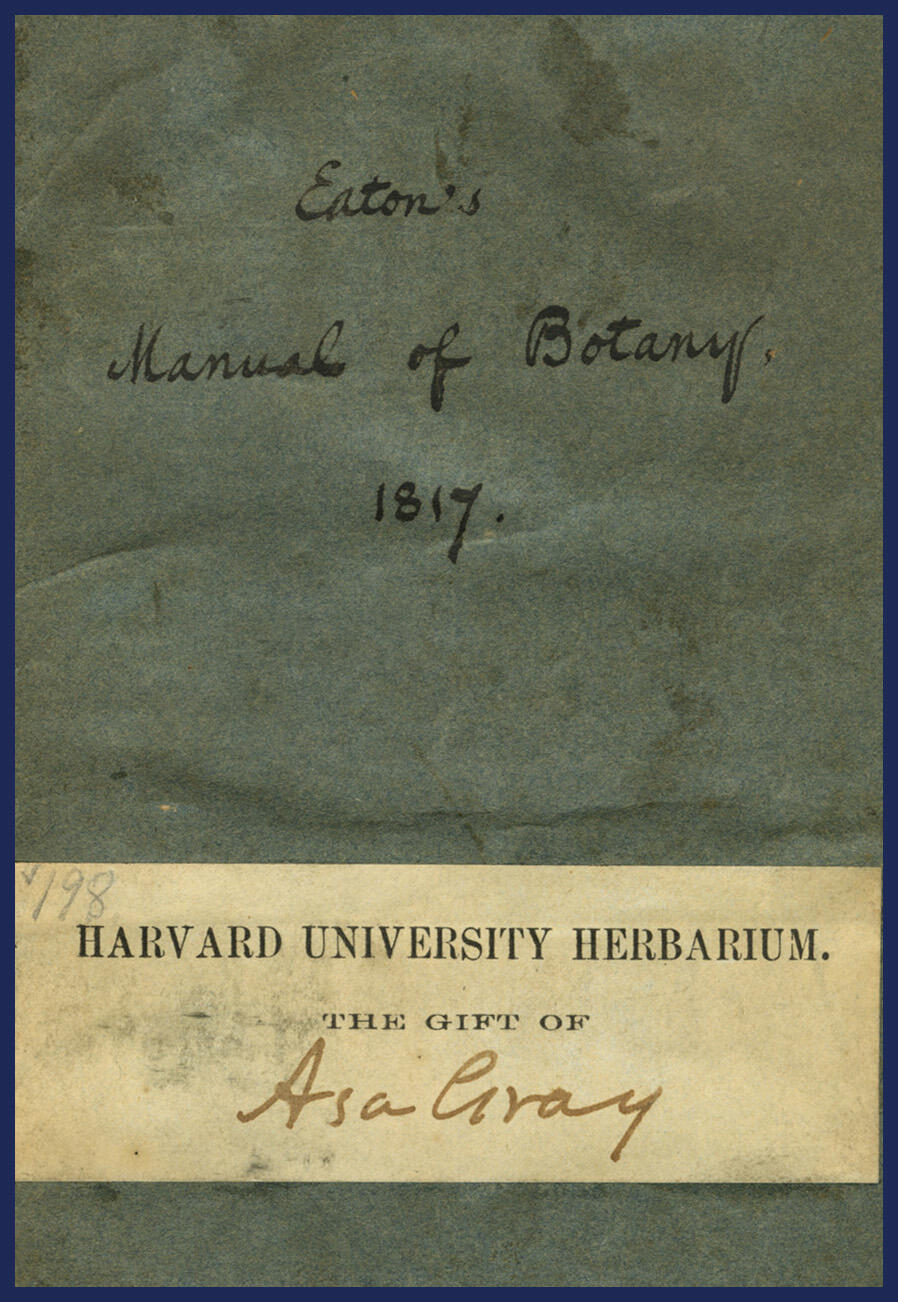

This was an important period of his life, for it was in the winter of 1827-8 that his interest in botany was awakened by reading an article on the subject in Brewster's Edinburgh Encyclopaedia. The next spring he eagerly watched for the first flower and, with the aid of Eaton's Manual, arranged on the old Linnaean System, he found it to be the little Claytonia virginica or Spring Beauty. During this time, he studied with Dr. Priest in his native town and was a pupil of Dr. John F. Trowbridge, of Bridgewater. The correspondence which he carried on with Dr. Lewis C. Beck, an eminent botanist, in regard to the botanical specimens which he had been collecting and studying, led to his going to New York and making the acquaintance of Dr. John Torrey, with whom he had already entered into a correspondence which lasted through the latter's life. Dr. Torrey was, at that time, undoubtedly the most distinguished botanist in America, and his strong and marked character impressed itself firmly upon the mind of young Gray.

This was an important period of his life, for it was in the winter of 1827-8 that his interest in botany was awakened by reading an article on the subject in Brewster's Edinburgh Encyclopaedia. The next spring he eagerly watched for the first flower and, with the aid of Eaton's Manual, arranged on the old Linnaean System, he found it to be the little Claytonia virginica or Spring Beauty. During this time, he studied with Dr. Priest in his native town and was a pupil of Dr. John F. Trowbridge, of Bridgewater. The correspondence which he carried on with Dr. Lewis C. Beck, an eminent botanist, in regard to the botanical specimens which he had been collecting and studying, led to his going to New York and making the acquaintance of Dr. John Torrey, with whom he had already entered into a correspondence which lasted through the latter's life. Dr. Torrey was, at that time, undoubtedly the most distinguished botanist in America, and his strong and marked character impressed itself firmly upon the mind of young Gray.

Dr. Gray's early interests were not confined to botany alone, for, about this time, he delivered lectures on chemistry, mineralogy and geology, as well as botany, at Mr. Bartlett's school in Utica. In 1833 Dr. Gray became the assistant of Dr. Torrey, who held the position of Professor of Chemistry and Botany in the N. Y. College of Physicians and Surgeons, and from this time Dr. Gray's life was entirely devoted to his favorite science. While there, he issued the first century of his North American Graminea and Cyperacae. A second century was issued shortly after, but the work was never completed. He stayed with Dr. Torrey till the spring of 1834, and then returned to Mr. Bartlett's school, intending to resume his work at the college after the summer vacation. The financial condition of the college, however, prevented this, much to his disappointment, but, shortly after, in 1836, through Dr. Torrey's kindness, he received the appointment of Curator of the New York Lyceum of Natural History. His first botanical papers were read before the Lyceum, in December, 1834, and were entitled A Monograph of the North American Rhyncospore and A Notice of Some New, Rare, or Otherwise Interesting Plants from the Northern and Western Portions of the State of New York. In 1836 he published his first text-book, Elements of Botany, a work conspicuous for its clear and sound reasoning and original thought. It treats of the principles of morphology, histology and vegetable physiology, and prepared the way for the Botanical Text-Book.

In 1835 or 1836 Dr. Gray was appointed botanist of the exploring expedition to the South Pacific, under Capt. Wilkes. During the long delays which attended the setting out of the expedition, preliminary work on the North American Flora, which had been many years before planned by Dr. Torrey, was begun. When the Wilkes expedition finally started, Dr. Gray resigned his position as botanist, and became Dr. Torrey's assistant in the new Flora. The work was arranged according to the Natural System, and in its scope was to be far ahead of anything that had hitherto appeared.

In 1838, Dr. Gray received the appointment of Professor of Botany in the University of Michigan, though he never filled the chair. He continued to work with Dr. Torrey in New York and, in July and October, 1838, Vol. I, Pts. 1 and 2 of the Flora of North America were published. In November of this year he sailed for Europe, to consult the various herbaria, which contained large collections of American plants made by foreign collectors. He visited England, Scotland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Austria, and met all the eminent botanists of the day, forming life-long friendships with some of them. His acquaintance with Sir J. D. Hooker dates from this time. He worked incessantly wherever he went and returned to America well stored with information for the continuance of the Flora. Vol. I, Pts. 3 and 4 of the Flora were published in June, 1840, completing the volume of 711 pages. Vol. II., Part I, appeared in May, 1841, Pt. 2 in April, 1842, while Pt. 3, completing the volume of 504 pages, was not published till February, 1843, after Dr. Gray had gone to Cambridge. Here the work was stopped, till it was resumed long after, single-handed, by Dr. Gray. The pressing professional duties of the two associates, besides the constant work required in elaborating and publishing the large collections that were constantly being brought in from different parts of our country, necessitated the suspension of the work, at least for the time.

In 1842, while visiting Mr. Benj. D. Greene in Boston, he accepted an invitation from President Quincy, Mr. Greene's father-in-law, to take the chair of Fisher Professor of Natural History in Harvard University, a position which he occupied till his death. Under him have grown up the vast herbarium and botanical library and garden, which, at the time of his going to Cambridge, were still in their infancy. At that time there was a single greenhouse, no herbarium, and but few botanical works. For eight years there had been no head at the Botanic Garden; since Thomas Nuttall resigned his position as curator, in 1834, to which he had been appointed in 1822, on the death of William D. Peck, the earliest and only professor before Dr. Gray. The Cambridge Botanic Garden was established in 1805, and Prof. Peck was appointed to direct it, as well as to give botanical lectures in the University. Through lack of funds, however, but little material of value for research was collected till Dr. Gray's accession.

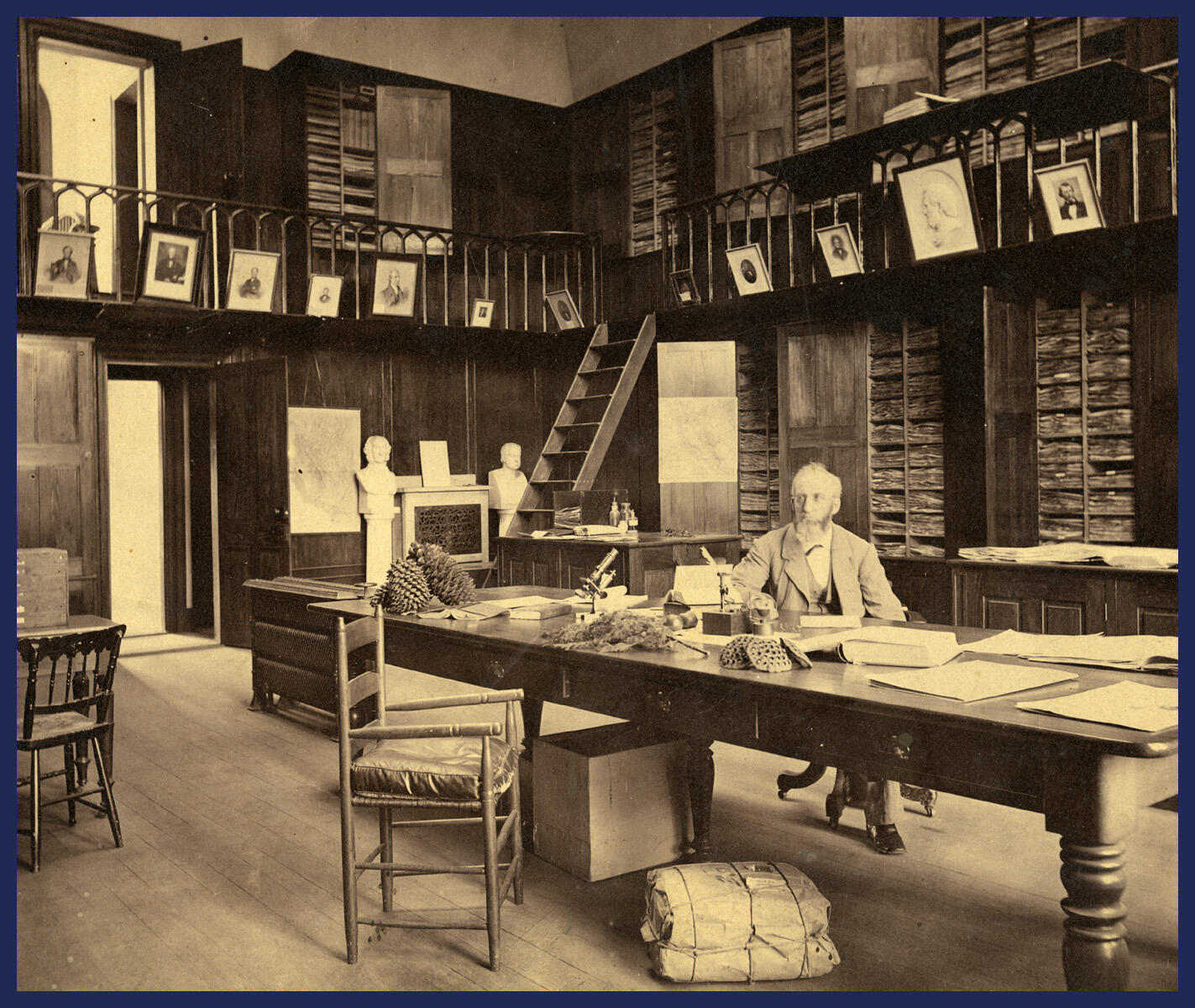

Mr. Peck built the house in Garden Street which has been the home of Dr. Gray for so many years and from which have come so many valuable works. The large and comfortable study, added in 1848, faces the south and east and looks out upon the garden, blooming with plants all through the growing season, while especially prominent is the great family of the Compositae, to which Dr. Gray has been so devoted. You were almost always sure, on going past the house to the herbarium, to see him either working at his study table, which was in the centre of the room, or bending over his microscope, which stood in the east window. A fireproof building, annexed to the house in 1864, contains the Library and Herbarium, both the gift of Dr. Gray, who said to the writer not long ago, " I have been all my life accumulating this library for you younger botanists to work with." The library now contains about 8,000 books and pamphlets, while the Herbarium ranks among the leading herbaria of the world.

In 1842 appeared the first edition of The Botanical Text Book, comprising an Introduction to Structural and Physiological Botany and the Principles of Systematic Botany, with an account of the chief natural Families of the vegetable Kingdom, and notices of the principal officinal or otherwise useful plants . This work was published shortly after his removal to Cambridge, having been written previously in New York, in the midst of his other engrossing labors. This work, so ably written in that clear and lucid style that characterizes all his writings, quickly passed through the first edition, and a second, third, fourth and fifth edition appeared in the years 1845, 1850, 1853 and 1857. Volume I of the sixth and last edition, published in 1879, under the same title, was entirely new, the other editions having been rewritten in good part. This edition it was decided to divide into distinct volumes, to better treat of the wide range of subjects, Dr. Gray writing the first part, which treats of Structural Botany or Organography on the Basis of Morphology, to which is added the principles of Taxonomy and Phytography and a Glossary of Botanical Terms. Volume II, on Physiological Botany, by Prof. Geo. L. Goodale, was published in 1885. Volume III, on Cryptogamic Botany, by Prof. Wm. G. Farlow, is soon, it is hoped, to appear, while Volume IV, on the Natural Orders of Phanogamous Plants, Dr. Gray, said nearly ten years ago, that he rather hoped than expected himself to draw up. It is certainly not to be wondered at that he never accomplished it.

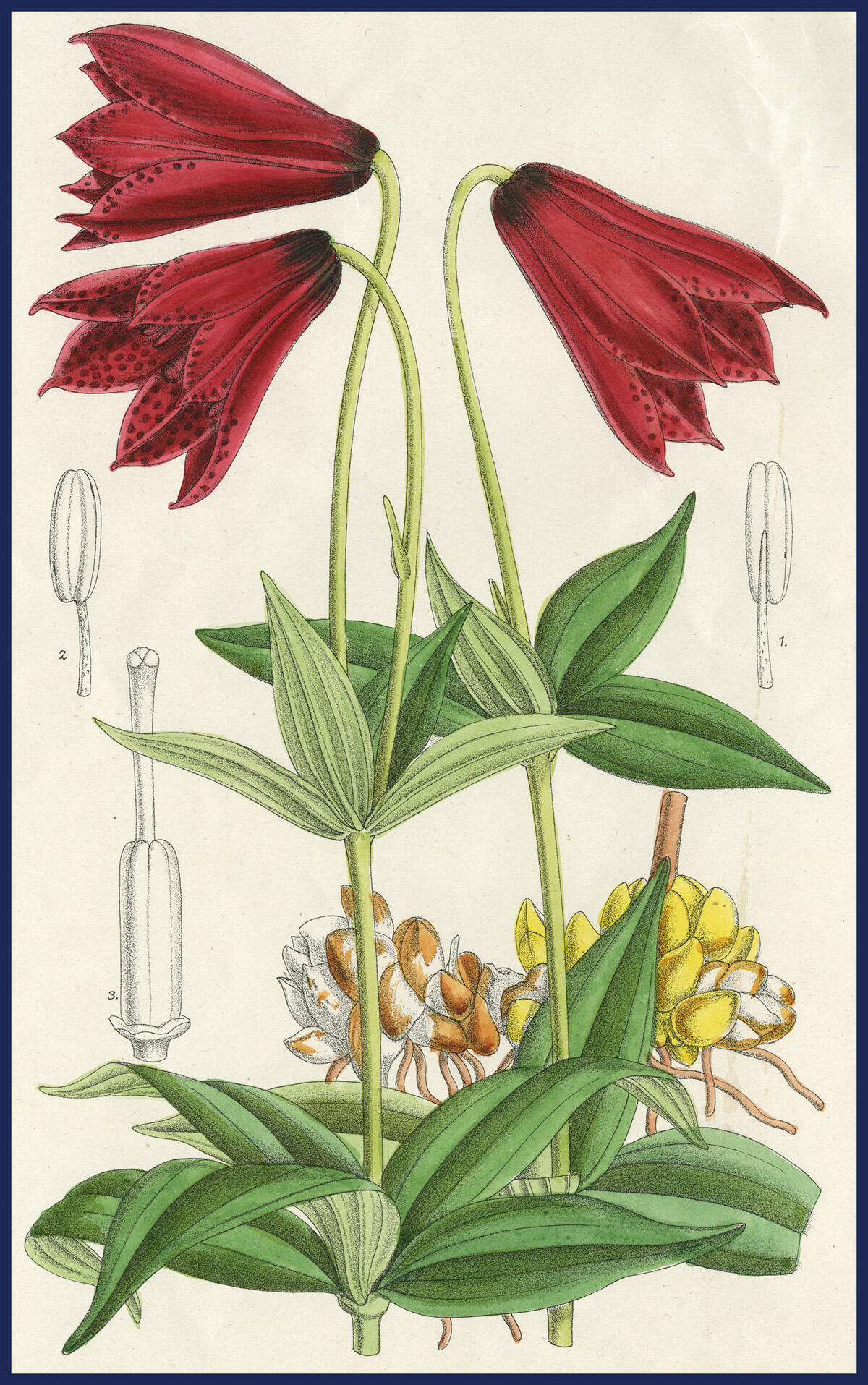

In 1846 he published, in the Memoirs of the American Academy, Chloris Boreali-Americana, being illustrations of new, rare or otherwise interesting North American plants, selected chiefly from those brought into cultivation at the Botanic Garden of Harvard University, Cambridge. This work was illustrated with ten plates. Only the first decade appeared. In 1848 was published his Genera Americae Boreali-Orientalis Illustrata, beautifully illustrated with figures and analyses from nature by Isaac Sprague. A second volume appeared in 1849. These two volumes contained one hundred and eighty-six plates, but unfortunately the work was not continued.

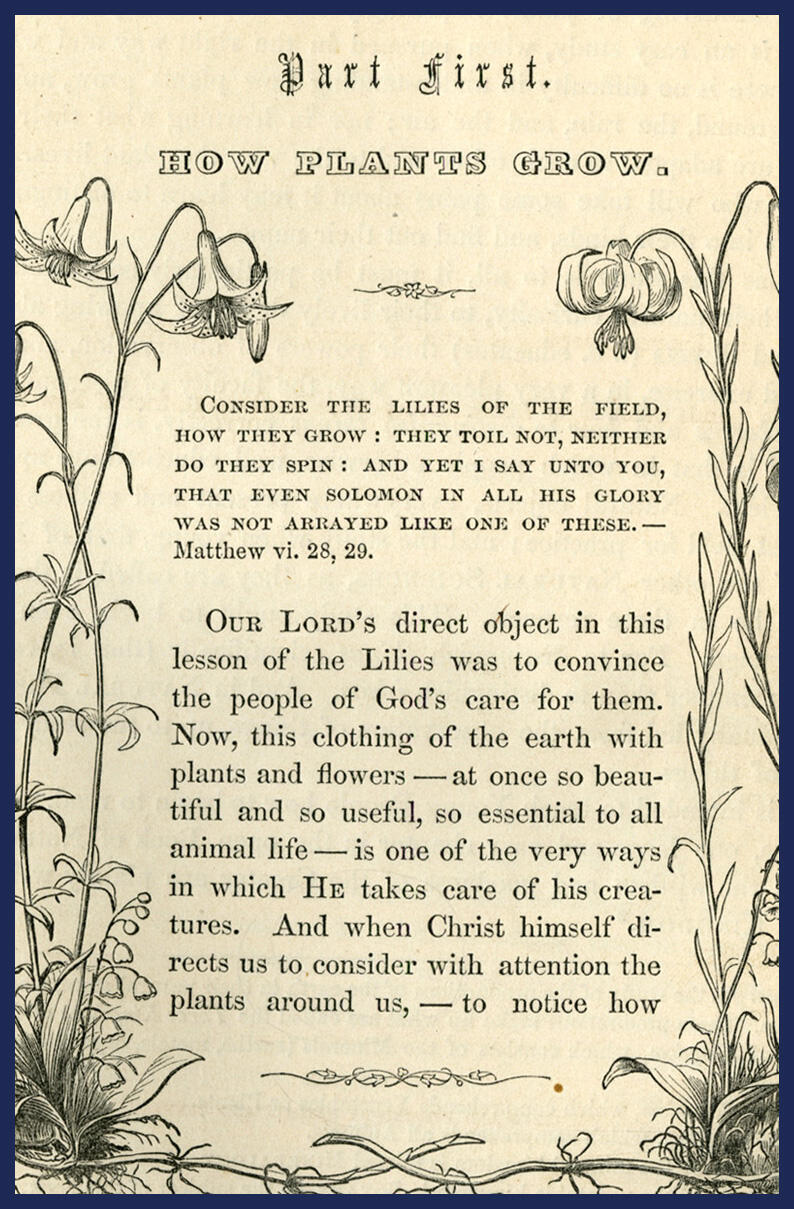

Dr. Gray's wonderful power of making botany interesting to the young is shown in his Botany for Young People. The first book on this subject is entitled How Plants Grow, and was published in 1858. It gives a simple introduction to Structural Botany, with a popular flora of common plants, both wild and cultivated, profusely illustrated. Many a botanist of the present day looks back with grateful recollections of the first impulse given to him in his botanical infancy by this book. The other book of this series is How Plants Behave, published in 1872, being a description in the very simplest language of how plants move, climb, employ insects to work for them, etc. In 1868 was published Field, Forest and Garden Botany, being a simple introduction to the common plants of the United States east of the Mississippi River, both wild and cultivated. Those who have used this book know how useful and indispensable it is in studying the plants of the garden. Dr. Gray was never satisfied with this work, and hoped to entirely revise it within a few years. In 1848 appeared a work, which, perhaps, more than any other, has been the constant companion of botanists of the Northeastern United States, both at home and in the field. To all those interested in a knowledge of our plants, the Manual is a household word. This book was entitled A Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States. It has passed through five editions, the last appearing in 1867.* Of this there have been eight issues. The first edition included the region from New England to Wisconsin, and south to Ohio and Pennsylvania, inclusive. It afterwards embraced all the country east of the Mississippi River and north of North Carolina and Tennessee.

Dr. Gray's wonderful power of making botany interesting to the young is shown in his Botany for Young People. The first book on this subject is entitled How Plants Grow, and was published in 1858. It gives a simple introduction to Structural Botany, with a popular flora of common plants, both wild and cultivated, profusely illustrated. Many a botanist of the present day looks back with grateful recollections of the first impulse given to him in his botanical infancy by this book. The other book of this series is How Plants Behave, published in 1872, being a description in the very simplest language of how plants move, climb, employ insects to work for them, etc. In 1868 was published Field, Forest and Garden Botany, being a simple introduction to the common plants of the United States east of the Mississippi River, both wild and cultivated. Those who have used this book know how useful and indispensable it is in studying the plants of the garden. Dr. Gray was never satisfied with this work, and hoped to entirely revise it within a few years. In 1848 appeared a work, which, perhaps, more than any other, has been the constant companion of botanists of the Northeastern United States, both at home and in the field. To all those interested in a knowledge of our plants, the Manual is a household word. This book was entitled A Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States. It has passed through five editions, the last appearing in 1867.* Of this there have been eight issues. The first edition included the region from New England to Wisconsin, and south to Ohio and Pennsylvania, inclusive. It afterwards embraced all the country east of the Mississippi River and north of North Carolina and Tennessee.

In 1857 he published his First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology, with a glossary of botanical terms, largely used as a text-book for educational purposes. This book Dr. Gray entirely revised and published in 1887, under the title Elements of Botany, and it is a very interesting fact that he should have given to this, his last text-book as well as his last published work, the same name that he had previously given to the first one, published over fifty years before. The two books are a most fitting Alpha and Omega to his industrious life. He always spoke with much enthusiasm in regard to this revised work and seemed much pleased with the result. It is interesting to compare the two editions and to see how many of the definitions Dr. Gray found it impossible to improve upon, though thirty years had elapsed since the publication of the first edition. The greater part of the work, however, is much changed to keep pace with the advance of the science.

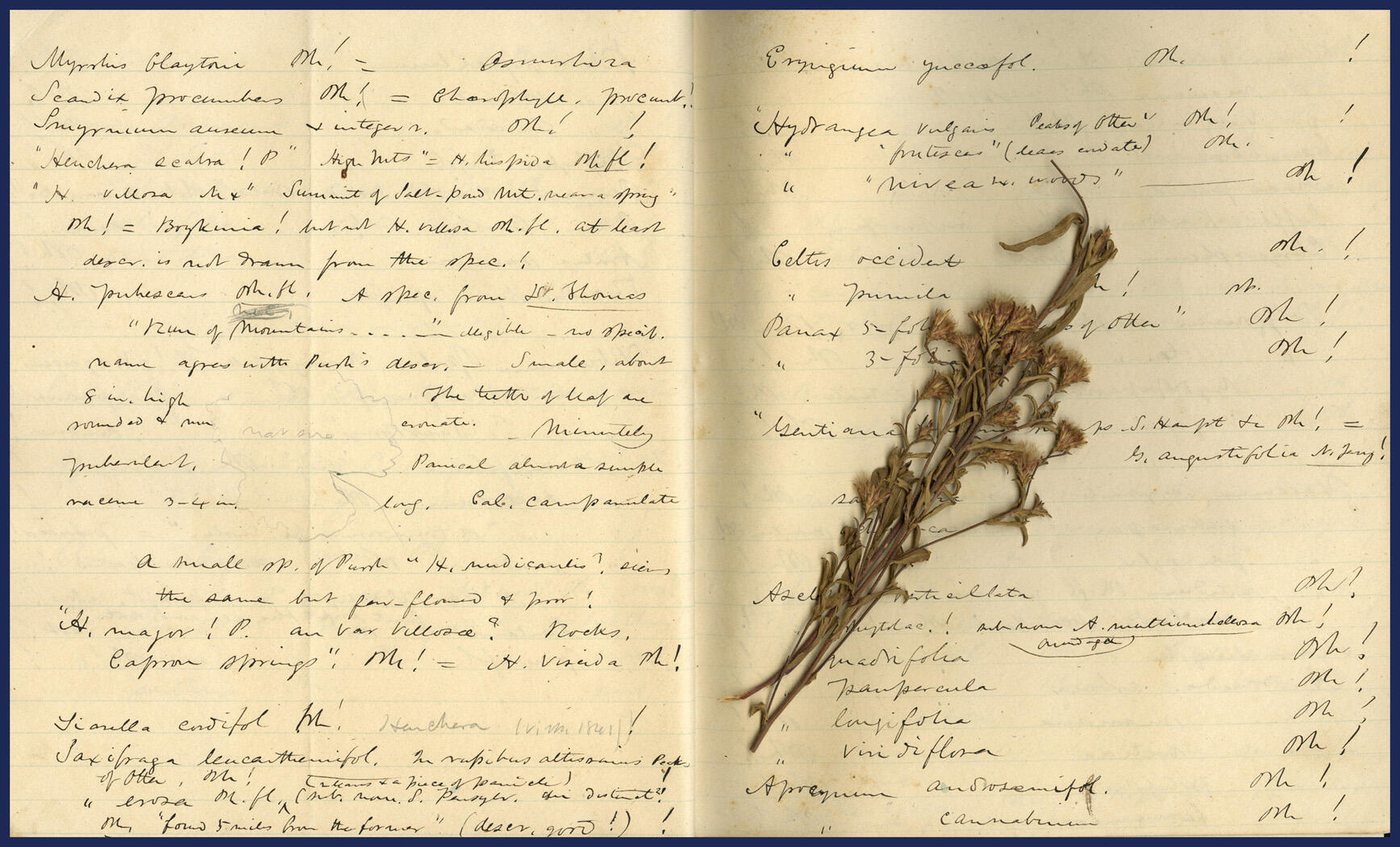

For thirty years following Dr. Gray's assuming the professorship at Cambridge, he was constantly engaged in his professional duties, beside building up the library and herbarium and taking charge of the garden. His former pupils are now scattered far and wide, many of them among our leading botanists, who cherish the warmest remembrances of a man who so patiently and skillfully guided them in their early studies. During all this period our country was being explored farther and farther to the west, and fresh material, collected by botanists on government expeditions and surveys, was pouring in to the Botanic Garden. The careful elaboration and publishing of these collections was done with a masterly hand, and appear, with the many contributions to botanical science which Dr. Gray was constantly making till his death, in the Proceedings and Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; American Journal of Science, of which he was associate editor in 1871; Annals of the New York Lyceum of Natural History; Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge; North American Review; Journal of the Boston Society of Natural History; Proceedings of the Philadelphia and California Academies of Natural Science; The American Naturalist; Government Reports; Botanical Gazette; in the BULLETIN, beside Hooker's Journal of Botany and the Journal of the Linnean Society.

For thirty years following Dr. Gray's assuming the professorship at Cambridge, he was constantly engaged in his professional duties, beside building up the library and herbarium and taking charge of the garden. His former pupils are now scattered far and wide, many of them among our leading botanists, who cherish the warmest remembrances of a man who so patiently and skillfully guided them in their early studies. During all this period our country was being explored farther and farther to the west, and fresh material, collected by botanists on government expeditions and surveys, was pouring in to the Botanic Garden. The careful elaboration and publishing of these collections was done with a masterly hand, and appear, with the many contributions to botanical science which Dr. Gray was constantly making till his death, in the Proceedings and Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; American Journal of Science, of which he was associate editor in 1871; Annals of the New York Lyceum of Natural History; Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge; North American Review; Journal of the Boston Society of Natural History; Proceedings of the Philadelphia and California Academies of Natural Science; The American Naturalist; Government Reports; Botanical Gazette; in the BULLETIN, beside Hooker's Journal of Botany and the Journal of the Linnean Society.

Among them may be mentioned accounts of collections of plants made in 1846 by Fendler, in New Mexico; in 1849 by Chas. Wright, near the Texan boundary of the U. S.; in 1851 and 1852 by Geo. Thurber, botanist to the Mexican Boundary Survey; and in 1845-6 and 1847-8 by Dr. F. Lindheimer, in Western Texas, in which Dr. Gray was aided by Dr. Geo. Engelmann; Forest Geography and Archeology, delivered in 1878 before the Boston Natural History Society, and published in the American Journal; Science and Religion, delivered before the divinity school at Yale College, on the subject of the Darwinian theory and published in book form in 1880, and many others. His botany of the Wilkes expedition, published in 1854 with one hundred handsome plates, is alone a monument to him.

Dr. Gray's position in regard to Darwinism is a very interesting one. A man of the deepest religious convictions, thoroughly imbued through his whole life with a firm and reverent belief in the Divine Creator of all things, he accepted scientifically and in his own fashion, he said, the theory of Charles Darwin, while philosophically he was a convinced theist. His paper on the "Diagnostic Character of Certain New Species of Plants, collected by Chas. Wright in Japan, with Relations of the Japanese Flora to that of North America", remarkable for its clear and lucid reasoning, shows plainly his ideas on the theory of distribution, while in the next year, March, 1860, was published in the American Journal his "Review of the Origin of Species by Chas. Darwin," published in London in 1859. In this article he refers to Robert Chambers as "The shadowy author of the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation," a work which appeared in 1844 and found little favor with Dr. Gray, who says, " He would explain the whole progressive evolution of Nature by virtue of an inherent tendency to development, thus giving us a word in place of a natural cause." Of Darwin's treatment of the question he speaks with enthusiasm, though he thinks there are still many important questions unsolved. He does not consider the Survival of the Fittest in the Struggle for Life by Natural Selection incompatible with devout theism, and he says, "We leave it for profounder minds to establish, if they can, a rational distinction in kind, between his (the Creative Mind) working in Nature, carrying on operations, and in initiating those operations."

September 5, 1857, Dr. Gray received a letter from Darwin, explaining briefly his theory of Natural Selection, so that he must have been seriously considering these views before the publication of the Origin of Species. Darwin, in a letter to A. R. Wallace, dated May 18, 1860, says of this work, "Asa Gray fights like a hero in defence," while Francis Darwin, in the Life and Letters of Chas. Darwin, London, 1887, says, "Asa Gray fought the battle splendidly in the United States." His various essays and reviews pertaining to Darwinism were collected and published in 1876, in a book entitled Darwiniana, and include papers from the American Journal, Atlantic Monthly, The Nation, Nature, New York Tribune, a paper on Evolutionary Teleology, and a paper on Sequoia and its History; the Relations of North American to Northeastern Asian and to Tertiary Vegetation, read before the American Association for the Advancement of Science, at Dubuque, Iowa, August, 1872, on the occasion of his retiring from the Presidency. In this able paper, he explains the isolation of these giant trees on the theory of the Survival of the Fittest, and refers back to past geologic times, when Sequoias played a more important part on the surface of our globe. To show how Dr. Gray's mind was stored with information ready to be called into use at any moment, he said, on presenting a printed copy to the writer, that he wrote it in the cars while on his way from California to Dubuque.

In 1873 Dr. Gray was relieved from active duties in the college, beyond the care of the herbarium, while retaining his professorship, and enabled to devote much more of his time to his literary work. And now he began the continuance of the old Torrey and Gray Flora, but on quite a different plan. Over thirty years had passed since the last volume bf the Flora was published and, during that time, a rich fund for the prosecution of the work had accumulated, in the shape of the many valuable botanical contributions written by Dr. Gray and others, and the richly-stored herbarium at Cambridge. The old Flora being now antiquated and rare, it was determined not only to complete the work, but to re-write entirely the older portion. Dr. Gray brought to this great work the experience gathered by close application and study during his whole life, and published in 1878, Volume II, Part I, of The Synoptical Flora of North America (Gamopetalae after Composite). In 1884 appeared Volume I, Part 2 (Caprifoliaceae Compositae), thus completing the great division of the Gamopetale. This last publication covers the same ground as Volume II of the old Flora, and may well be called the crowning work of his life. It is almost entirely devoted to the Compositae, an order to which Dr. Gray had given the closest attention, both in this country and in the herbaria of Europe. The interest awakened among American botanists by his Studies of Aster and Solidago in the Older Herbaria, published in the Proceedings of the American Academy in 1882, shows how eagerly the publication of the volume was awaited. In 1886 supplements were published to each part and bound with the two parts in a single volume. This great work at once raises Dr. Gray to the highest rank among the systematic botanists of the world.

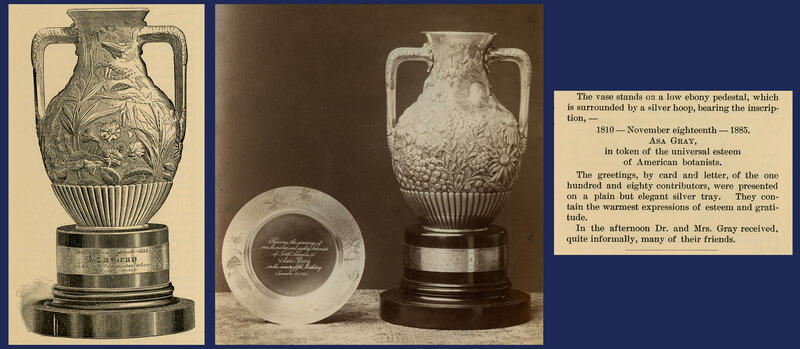

On the occasion of Dr. Gray's seventy-fifth birthday, the 18th of Nov., 1885, the botanists of North America, led by the editors of the Botanical Gazette, presented to the distinguished botanist a handsome silver vase, with the inscription, "1810, November eighteenth, 1885. Asa Gray, in token of the universal esteem of American Botanists." The vase, a full account of which appeared in the Gazette at the time, was beautifully embossed with flowers peculiarly appropriate to the occasion. Prominent among them and fitly commemorating the name of our beloved friend and teacher, were Grayia polygaloides, Lilium Grayi and Notholana Grayi.

On the occasion of Dr. Gray's seventy-fifth birthday, the 18th of Nov., 1885, the botanists of North America, led by the editors of the Botanical Gazette, presented to the distinguished botanist a handsome silver vase, with the inscription, "1810, November eighteenth, 1885. Asa Gray, in token of the universal esteem of American Botanists." The vase, a full account of which appeared in the Gazette at the time, was beautifully embossed with flowers peculiarly appropriate to the occasion. Prominent among them and fitly commemorating the name of our beloved friend and teacher, were Grayia polygaloides, Lilium Grayi and Notholana Grayi.

A silver salver, accompanying the vase, received the cards of the givers, and was marked with the inscription, "Bearing the greetings of one hundred and eighty botanists of North America to Asa Gray on his 75th birthday, Nov. 18, 1885." It was a beautiful tribute to a man so universally loved and honored.

Dr. Gray was married in 1848 to Jane L. Loring, the daughter of the late Hon. Chas. G. Loring, one of the most distinguished lawyers of the Boston bar. She was a most devoted companion and assistant in all his labors, and accompanied him on most of his journeys. After assuming the Professorship at Cambridge, he made five trips to Europe, the first time being in June, 1850, when he and Mrs. Gray went to England by a sailing vessel, the principal reason for the trip being to work up the plants of the Wilkes expedition. They traveled in Switzerland, and at Geneva Dr. Gray worked for a while in De Candolle's herbarium. From there they went to Munich and saw Von Martius, the distinguished naturalist and traveler, whose work on the palms is one of the most valuable contributions to science. This was the renewal of a warm friendship formed in 1839. They returned by Holland to England and, early in October of the same year, went into Herefordshire to the country place of George Bentham, where they spent two months, Mr. Bentham going over, with Dr. Gray, the collection which he had taken out with him from America on this visit. At Christmas time they went to Kew, where Dr. Gray worked in Sir William Hooker's herbarium, which was then in his own house; and also in the British Museum, Robert Brown-- being at the time there. Dr. Gray says of this distinguished man, that he, "Next to Jussieu, did more than any other botanist for the proper establishment and correct characterization of natural orders." From Kew they proceeded to Paris, where for six weeks Dr. Gray worked at the Jardin des Plantes and in P. Barker Webb's herbarium, and then, returning to England, they sailed for America by steamer in August, 1851.

The second trip to Europe was a short one, occupying from August to September, 1855, when Dr. Gray went to Paris to bring home his brother-in-law, who had been ill there with typhoid fever. He saw, however, some of his old friends. In September, 1868, Dr. Gray again sailed for Europe with his wife, and spent the autumns of 1868 and 1869 at Kew, hard at work. He also worked in Paris, Munich and Geneva, and visited herbaria over a large part of the continent. On this trip, however, he took more holidays than in any journey except the last. In December, 1868, they went up the Nile in Egypt, and returned to Cairo in March, passing twelve weeks in a " dahabeeah " with a family party. Dr. Gray did a little botanizing, but said that a land that had been cultivated 5,000 years was a poor land to botanize in. However, when the desert was within reach, as it occasionally was, and they landed for a walk, he made some specimens and he would say that the desert had more plants in half an hour, than cultivated Egypt in a week. They ascended the river as far as Wady-Halfa, in Nubia, where the cataracts stop navigation. They returned home to America in November, 1869. Again, early in September, 1880, Dr. and Mrs. Gray went to Europe, and this time Dr. Gray saw the Herbarium at Madrid and worked for some time in Paris, and for a long time at Kew, the British Museum, etc. Plants were also sent to him from German herbaria and the Jardin des Plantes, etc., to assist his studies at Kew. He worked also in some of the Italian herbaria. They sailed for home by the end of October, 1881.

The second trip to Europe was a short one, occupying from August to September, 1855, when Dr. Gray went to Paris to bring home his brother-in-law, who had been ill there with typhoid fever. He saw, however, some of his old friends. In September, 1868, Dr. Gray again sailed for Europe with his wife, and spent the autumns of 1868 and 1869 at Kew, hard at work. He also worked in Paris, Munich and Geneva, and visited herbaria over a large part of the continent. On this trip, however, he took more holidays than in any journey except the last. In December, 1868, they went up the Nile in Egypt, and returned to Cairo in March, passing twelve weeks in a " dahabeeah " with a family party. Dr. Gray did a little botanizing, but said that a land that had been cultivated 5,000 years was a poor land to botanize in. However, when the desert was within reach, as it occasionally was, and they landed for a walk, he made some specimens and he would say that the desert had more plants in half an hour, than cultivated Egypt in a week. They ascended the river as far as Wady-Halfa, in Nubia, where the cataracts stop navigation. They returned home to America in November, 1869. Again, early in September, 1880, Dr. and Mrs. Gray went to Europe, and this time Dr. Gray saw the Herbarium at Madrid and worked for some time in Paris, and for a long time at Kew, the British Museum, etc. Plants were also sent to him from German herbaria and the Jardin des Plantes, etc., to assist his studies at Kew. He worked also in some of the Italian herbaria. They sailed for home by the end of October, 1881.

The last trip to Europe was taken in April, 1887. This journey was mostly a holiday one, though Dr. Gray did some work at Kew, besides going over the Lamarck herbarium at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Three universities honored themselves by conferring degrees upon Dr. Gray at this time. When the University of Cambridge bestowed the degree of Doctor of Science, Dr. Sandys closed his address, which was written in Latin, in the following words, "This man who has so long adorned his fair science by his labors and his life, even unto a hoary age, 'bearing,' as the poet says, 'the white blossoms of a blameless life,' him, I say, we gladly crown, at least with these flowerets of praise, with this corolla of honor (His saltem laudis flosculis, hac saltem honoris corolla, libenter coronamus.) For many, many years may Asa Gray, the venerable priest of Flora (Florae sacerdos venerabilis), render more illustrious this academic crown!" The University of Edinburgh conferred the degree of LLD., and the University of Oxford that of D.C.L. He was also at this time elected an honorary member of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, England.

There was scarcely a society of note, either in this country or in Europe, that did not claim Dr. Gray as an active, foreign, honorary or corresponding member. His name is connected with seventy different societies, from many of which he received distinguished honors. His first degree was an M. D. in 1831, from the College of Medicine and Surgery, at Fairfield, N. Y. Among others, were an A.M. in 1844 and a LL.D. in 1875, both from Harvard University. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy in 1841 and was its President from 1863 to 1873. In 1850 he became a Foreign Member of the Linnaean Society of London and, in 1852, a Corresponding Member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In 1878 he was elected a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Science of the Institute of France.

Dr. Gray made three trips to California, the first one in 1872. The next one lasted nearly four months, beginning in July, 1877. Mrs. Gray and Sir J. D. Hooker were of the party. They traveled a good deal in Colorado and the Sierra Nevada Mts., going as far north as Mt. Shasta in Northern California. The third trip was in 1885, by way of New Orleans, New Mexico and Southern California, as far north as Chico. From El Paso the party made a detour into Mexico. They left in February, returning early in May. Dr. Gray visited the Alleghany Mts. four times, the first trip being in the summer of 1841, when he visited Grandfather and Roan Mts. in North Carolina. On the second trip, in 1843, he was accompanied by Mr. W. S. Sullivant of Ohio, and on the third trip, in 1876, by Mrs. Gray, Mr J. H. Redfield, Mr. Wm. M. Canby and Dr. and Mrs. Geo. Engelmann. On the last occasion, in 1879, a large party was formed, who visited Roan Mt. and other localities and, especially, the interesting spot where Shortia galacifolia, with its romantic history which identifies the little plant so closely with Dr. Gray, still grows.

Dr. Gray made three trips to California, the first one in 1872. The next one lasted nearly four months, beginning in July, 1877. Mrs. Gray and Sir J. D. Hooker were of the party. They traveled a good deal in Colorado and the Sierra Nevada Mts., going as far north as Mt. Shasta in Northern California. The third trip was in 1885, by way of New Orleans, New Mexico and Southern California, as far north as Chico. From El Paso the party made a detour into Mexico. They left in February, returning early in May. Dr. Gray visited the Alleghany Mts. four times, the first trip being in the summer of 1841, when he visited Grandfather and Roan Mts. in North Carolina. On the second trip, in 1843, he was accompanied by Mr. W. S. Sullivant of Ohio, and on the third trip, in 1876, by Mrs. Gray, Mr J. H. Redfield, Mr. Wm. M. Canby and Dr. and Mrs. Geo. Engelmann. On the last occasion, in 1879, a large party was formed, who visited Roan Mt. and other localities and, especially, the interesting spot where Shortia galacifolia, with its romantic history which identifies the little plant so closely with Dr. Gray, still grows.

After Dr. Gray's last return from Europe, he pressed on with renewed zeal, to complete Vol. I, Part I, of the Synoptical Flora, which was to embrace the Polypetalae. The work had been far advanced already through his own labors and those of his able co-workers, Dr. Sereno Watson and others. Much had been done, but much remained to be done. All the botanists of North America, in particular, were anxiously waiting and praying that the life of their master might be spared to complete this, his last monument. It was ordained otherwise. On the 28th, of Nov., 1887, while working on the Grape Vines of North America, included in the order Vitacae, he was stricken with paralysis, and for just nine weeks, he lingered between life and death. His recovery was impossible, and on the 30th of Jan., 1888, he quietly breathed his last. His death is a great blow to American botanists and a sad loss to his wide circle of friends. His light step and cheery voice will be sadly missed from the Cambridge Herbarium. Ever ready to assist and counsel those who came to him for advice, he leaves behind him many sad but grateful hearts. But he still lives in his works, and as long as the science of botany is studied, his name will be a familiar one.

*There have now been 8 editions, the last a centennial edition done by Merritt Lyndon Fernald.