Jane Lathrop Loring Gray

By the summer of 1842, Asa Gray was settling in at Harvard and in Cambridge. He found lodgings halfway between the college and the Garden. For $3.00 a week he had a three room apartment: one room for his office, one for a bedroom, and the third, a "small nearly dark bedroom which I shall shelve and use for my herbarium."

Boston was surprisingly quiet, as many of the wealthier Cantabrigians were summering at the shore, but this affected Gray not at all. He spent his early days exploring and inspecting libraries and churches as well as introducing himself to local botanists. Even with a decreased population, Gray began to realize that the women of Massachusetts were unlike those he was used to. In a letter to John Torrey Gray writes:

There's nothing like down East for learned women. Why, even the factory-girls at Lowell edit entirely a magazine, which an excellent judge told me has many better-written articles than the "North American Review." Some of them having fitted their brothers for college at home, come to Lowell to earn money enough to send them through!! Vivent les femmes. There will be no use for men in this region, presently. Even my own occupation may soon be gone; for I am told that Mrs. Ripley is the best botanist of the country round.

Asa Gray to John Torrey, 25 July 1842

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

However, Gray did not have much time to contemplate the joys offered by eastern women. Much of his time was spent on his teaching duties, improving and developing Harvard's Botanic Garden, writing articles for Silliman's Journal, working on his Botanical Textbook, and involvement with his church, Albro's Congregational Church.

During these early years in Cambridge, Gray also became a member of the Boston Society of Natural History and was asked to give a few lectures, including their annual address in 1843. Meanwhile, Gray also served as corresponding secretary for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and he even organized a scientific club comprising mainly college faculty and including such august members as historian Jared Sparks, philosopher Francis Bowen, and Harvard's president Josiah Quincy. As Gray reported to Mrs. Torrey in a letter dated 14 December 1842: "So you see I have work enough ahead, if I live, to give me both occupation and anxiety."

It would seem impossible for Gray to add any more obligations to his already overscheduled life. However, in early 1844 Gray was engaged to do a series of twelve lectures at the new Lowell Institute. (1) John A. Lowell offered Gray $1,000 for a series of twelve lectures. This was the equivalent of a year's salary at Harvard (or about $22,757 in adjusted dollars), and impossible for Gray to pass up.

The return of my birthday brings to mind, among other shortcomings that I have neglected to write home since my return. I have been very busy of course, since the 3rd of the month, when I reached Cambridge, in answering the heap of letters that had accumulated and in other business. And I have but just found time to commence the preparation of a course of lectures before the Lowell Institute, which is to commence on the 27th of February, and which will give me plenty of labor and anxiety until they are over.

Asa Gray to his father, 18 November 1843

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

Gray's lectures were a success and he was asked to offer a second series in 1845 and a third in 1846. Gray's protégé and Harvard professor William Gilson Farlow (1844-1919) wrote that it was at one of these Lowell lectures that Asa met his future wife, Jane Lathrop Loring.

Jane Lathrop Loring was born in Boston on August 21, 1821, the daughter of Charles Greely Loring and Anna Pierce (Brace) Loring. Charles Loring (Harvard AB 1812, LL.D. 1850) was a prominent Boston lawyer, a Harvard College fellow from 1838-1857, and a Massachusetts state senator in 1862. While the family lived in Boston, Jane spent a good deal of time in her mother's home town of Litchfield, Connecticut. She served as her father's hostess and mother to her two younger siblings, Susan Mary (b. 1823) and Charles Greely (b. 1828) after their mother died in 1836. She was only 15 at the time and often felt overwhelmed by the responsibility and worried that she was not doing as well by her siblings as a mother would. She felt, though, that caring for them and for her father was an important duty, not to be shirked. Charles G. Loring did marry again in 1840 but not even four years later, when Jane was 22, his second bride, Mary Ann Putnam, died as well, leaving Jane to once again assume the responsibilities of the household.

Jane was intelligent, curious, friendly, and warm hearted. According to Hunter Dupree's biography of Asa Gray, in her own opinion Jane was a wild and careless creature. She saw herself as full of natural life and high spirits and sometimes wanting in dignity. Gray's younger brother George, who lived with Asa in the Botanic Garden house before the marriage, described Jane as "womanly & good, laughs frequently & heartily as if she enjoys it."

Unfortunately, much like her father, Charles G. Loring, Jane was frequently in poor health. She tired easily and often. There was no clear medical diagnosis but often suffered from digestive complaints and would take to her bed for days at a time. Her condition worsened after their marriage and, with no clear cure, she suffered from this weakness for her entire life .

However, in the early 1840s, around the time that Gray was establishing himself in the Boston scientific community, Jane was still in relatively good health and, as a woman in her early 20s, had begun to think of her social life. She wrote to her mother's sister Mary Pierce:

I have not been able to make my grand coming out this winter, because there have been no balls. I do not know when there has been such a quiet winter in Boston, there has not been a ball this year. It is owing partly to the hard times and partly perhaps to the lectures which are without number & end; literally Bostonians are lecture-mad, the theatres even are obliged to be closed.

Jane Loring to Mary Pierce, 29 January 184_

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

Jane must have been caught up in this lecture fever and attended at least one of the Lowell Lectures that Asa gave during this time and they were somehow introduced. Sadly, almost all of the details surrounding Asa Gray and Jane Lathrop Loring's early relationship have been lost. What few clues there are can be gleaned from their correspondence to family and colleagues.

Jane met Asa at an opportune time in his life when he was seriously thinking about marriage. At least one of the reasons for this was time management. Writing to colleagues, Gray indicated that he needed a wife to help organize and reply to his correspondence. However, a few letters also seem to indicate a more emotional wish to marry than just having someone to serve as a secretary and help with his work. In 1843, Gray wrote to Elizabeth Torrey, wife of his mentor, Dr. John Torrey.

I found on my return a letter from my brother, announcing the approaching marriage of my youngest sister; which event took place, I suppose, on the 20th inst. the day I left New York. Had I received the letter in New York, I should have arranged to be present on the occasion. I wonder if my turn will ever come!

Asa Gray to Elizabeth Torrey, 22 July 1843

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

The events between their first meeting and the proposal are not available to us at this time. According to the customs of the time, Asa and Jane never spent time alone or discussed their feelings towards each other, as that would not have been appropriate. Instead Gray visited with the family, he helped them in their garden and rockery, and also shared Sunday dinner with them most weeks. By early 1847 Asa had decided that he would like to ask Jane to be his wife. However, her decision was a difficult one and her duty to her family came before any thoughts of romance.

On March 3, 1847, Gray decided it was time to make his intentions clear and wrote to Charles Loring, Jane's father, to request his permission to ask for Jane's hand in marriage. Charles Loring replied the next day:

I received your note yesterday at noon in the midst of an engagement from which I could obtain no release until late at evening, which prevented an earlier reply.

I appreciate & reciprocate the confidence in which it was written, & assure you that there is no person to whom I should, with some trust to cheerfully entrust the welfare of my daughter than yourself: and I could not express a higher regard for you, as she is dearer to me than life. I have no reason to doubt that her hand and affections are free.

To your remaining inquiry I am unable to give any satisfactory answer. You certainly possess her entire esteem and respect and your society is eminently agreeable to her as well as to myself. Her sentiments however, upon the subject of alliance are peculiar and may be affected by other considerations. I should not feel at liberty to anticipate her decision without reference to her, which the nature of your communication of course entirely precluded...

...I might perhaps add that from remarks occasionally made in conversation upon the general subject without reference to individuals I learned that she is [impressed] with the thought that her duty requires her to remain in her present position - I by no means concur in this opinion, but the subject is one upon which my views would probably have far less influence upon her than any other where my apparent comfort were not so deeply involved.

Charles G. Loring to Asa Gray, 4 March 1847

Harvard University Archives

By this time Jane's younger sister, Susan Mary Loring, had married Patrick Tracy Jackson and was pregnant with their second child. However, Jane's father was correct, her sense of responsibility to her family still weighed heavily on her mind. Whether correct or not, Jane felt that it was her job to care for her father and brother and leaving them was not something to be addressed lightly. Reading her letters from this time it is readily apparent that she cares for Dr. Gray, but she is constrained by her sense of duty to her family. The actual proposal comes sometime in March or April 1847. While Jane does not outright refuse Gray's offer of marriage, neither does she say yes. Her difficulty in deciding the proper course and the inconsistency of her feelings caused her quite a bit of anguish. She worried about hurting Gray and about abandoning her father. At the end of April 1847, almost 7 weeks after Charles's reply to Gray, Jane wrote again to her mother's sister, Mary Pierce, for advice.

I have been in a better state of mind for I have decided to let matters take their course & have an explanation if it comes - I am as determined as at first as to what the answer shall be, for I cannot see it right to leave father; but it is a satisfaction I believe I should not have strength to deny myself if I would now -I fear sometimes he [Dr. Gray] may think I have done very wrong, but it is not a wilful wrong to him I am sure - I still think my great fault has been in not having been more decided long ago - it is partly the consequence of his own perseverance - I wish father had never said a word for me! - He is very attentive in sending flowers & books - very kind! I do not like to think that he should blame me, that I have injured him! – Sometimes I think father must think me strange & not treating him with the confidence I have always used; he sees it is very different from what it was the first of the winter, & I say nothing to him! – But how can I speak? I know just what he would insist upon were I to tell him & I do not mean that he shall know the final explanation. And yet sometimes when he sits so still after Dr. - has gone I think he is thinking I am not the Jeannie I was, & that when my confidence would have been most valuable I am silent. And he trusts so perfectly in me!

The letter closes with a sad reminder of how the etiquette of the day made honest communication between Asa and Jane so difficult.

And yet it seems very selfish to be troubling you all who have cares enough - I sometimes wish you were here for I feel as if father might talk to you, & I should know more of what he thought & felt - I cannot speak to him - I cannot let him insist as I know he would on being left - I do not want him to know that I make any sacrifice - If we only met in company a little or sometimes alone! - But it is all so entirely in calls where father is almost always present, that he sees and knows everything that is going on -

Jane Loring to Mary Pierce, 25 April 1847

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

Although we do not have access to Jane's written reply to Gray, her later letter to her aunt charmingly illuminates how they became engaged. It was only a few short weeks after the previous letter but the entire landscape of their relationship had changed.

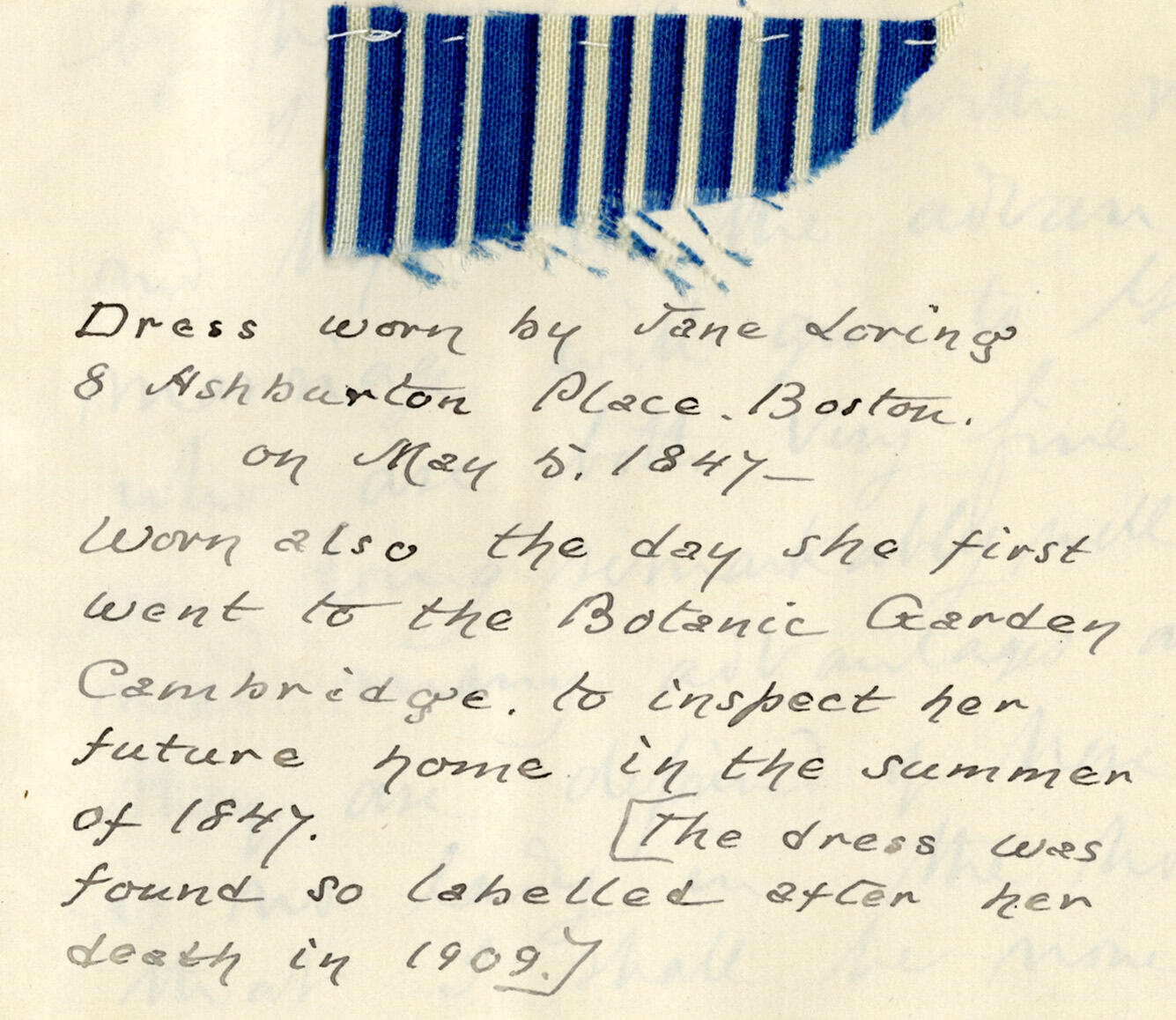

I must write to you, dear Aunt Mary, to tell you how happy I am! and I should have written before, had I not thought you would prefer waiting a day and getting a long letter, than to have a hurried line. And I am sure I am glad beside, for I am in a so much calmer frame of mind & understand my own feelings so much better, that I am sure my letter will be much more satisfactory - But I must begin & tell you the story from the beginning, that you may understand entirely how matters have been brought to so bright a conclusion -

I had a call a week ago yesterday [ ] but nothing different from usual, but Monday morng [sic] I received a beautiful box of the sweet little May flowers & a letter, so beautiful & noble, so afraid of being thought presumptuous & yet so perfectly keeping his own dignity! - Oh it is fortunate I am not a romantic young lady, or my sensibilities must have been very much shocked, for Nancy had come in to help me, & came up stairs as I was in the midst - I managed to tuck it behind the bed & sent her down to fix the flowers. But to get a chance for a second quiet perusal, I at last found my way into the garret & took a seat upon a roll of carpeting, thinking there I could not be interrupted without hearing that someone was coming - Then Lizzie came & I thought never would go; at last she & Nancy both took their departure, & I ran up stairs to write my answer. Just as I had begun Edmunds came to know about the carpets & some potatoes - I was seated again when back came Lizzie to sit & help me till I should go out. At last the only way to get rid of her, I put on my bonnet & went out. I went to the Dr.'s & Aunt Lizzie promised to come for my letter before dinner, & Uncle Charles would take care that it shld [sic] be sent - So I came home & stole into the house that no one need know I had got back, & managed to finish without interruption - I told him just the truth, that whatever my inclinations might be I could not leave father, and begged his forgiveness if he thought I had done wrong - I felt better after the letter had gone for I certainly had tried to do right, though I felt anxious to know what he would say - Tuesday morning I received a long letter, so kind and generous! Fully approving of all I had done, & saying he never had thought I could leave father; & proposing father should spend the winter at Cambridge, & how pleasant to him would be the summer at Beverly & asking whether I would not revise my decision, & propose this plan to father - He said so much about father, that it did not seem justice to Dr. G. that I should not show the letter to him, though I knew what he would say, & scarcely thought he would agree to the Cambridge plan - So Tuesday Evg [sic] I told him what had been going on, & why I had felt it should not be, & gave him the two letters to read telling him my answer to the first - he said at once that there must be no hesitation, that there was no hurry to make any arrangement about him, that he was the man of all others to please him, & that he felt my happiness quite secure - ...

I wrote a letter that evening saying, as I had before said to father, that the express & only condition which would make me consent, was that father's happiness was to be consulted first in all things, & I believe we both feel it most sincerely & will abide by it most strictly - I hope we may only persuade father of it - Oh such a condition as I was in by Tuesday night!

Jane actually made herself sick with overexcitement and took to bed until Wednesday afternoon when...

...a message came upstairs that Dr. Gray wished to see me a few moments - Sue must have suspected something, for I started up to go down; but on second thoughts concluded to smooth my hair as I was just off the bed, [which] she quite advised & at last she went & I went down - But sentimental stars never reigned over me - I had on my shabby old packing dress & a violent cold in my head! You know what my colds are! - Then as we sat there Edmunds came in for bags for the carpets - & "please mum, where shall I go for the oil" - Then Augusta called me to the door to give me some knitting directions I had asked for & to say "good bye" - Do you wonder I sighed for the privacy of Beverly? - However any head-ache was much better after he had gone, & I went into Grandfather's to tea & bade them all good-bye...

...a message came upstairs that Dr. Gray wished to see me a few moments - Sue must have suspected something, for I started up to go down; but on second thoughts concluded to smooth my hair as I was just off the bed, [which] she quite advised & at last she went & I went down - But sentimental stars never reigned over me - I had on my shabby old packing dress & a violent cold in my head! You know what my colds are! - Then as we sat there Edmunds came in for bags for the carpets - & "please mum, where shall I go for the oil" - Then Augusta called me to the door to give me some knitting directions I had asked for & to say "good bye" - Do you wonder I sighed for the privacy of Beverly? - However any head-ache was much better after he had gone, & I went into Grandfather's to tea & bade them all good-bye...Jane Loring to Mary Pierce, 9 May 1847

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

Once Jane agreed, Gray wrote to his family to let them know of his choice.

...The news is just this, I am engaged to be married to a lady who I think is every way calculated to make me happy. When we may look for the event is more than I can say, since it is only yesterday that the lady's promise has been obtained. - Certainly it will not be until fall, but I hope by that time, if it please God to spare our life and health. You will be anxious to know all about her, but it is not easy to give that information in writing. I hope you may see her and know her in due time. She lives in Boston where her father is a very eminent lawyer, and a man of the highest character. She has long been motherless, and her father lost a second wife very soon after marriage three or four years ago, since which Jane has been at the head of his family, her only sister (younger) having been some time married. Though born in Boston, her mother whose maiden name was Brace, was from Litchfield, Connecticut, where her relatives still reside. I have not yet told you her name. It is Jane Loring. Her age I suppose to be 25 or 26, though this of course I do not know directly. I suppose she would not be called handsome, but she has a face beaming with good temper and full of intelligence. - She is the perfect admiration of all her friends for her lovely and excellent qualities. - She is I believe a truly pious girl, and is indeed a person in whom I have the utmost confidence and trust. She moves in the best, though seldom the most brilliant circles of Boston. - Possesses all the usual accomplishments of persons in her station, but is most remarkable for a well-cultivated mind, and for her excellent practical powers.

Asa Gray to his mother, Roxana Gray, 6 May 1847

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

And Jane also wrote to her Aunt and described Gray, in much the same terms that he had described her to his mother.

And now, Aunt Mary, what shall I say about the object of my choice - Shall I try to give a personal description - He is not handsome - about father's height, very straight black hair, & bright black eyes - A very intelligent face, & lights up when he is interested - Perhaps you would not be so struck with him at first for his manner is so excitable that he does not do himself justice, but I am sure you could not be with him long & hear him talk without being interested in spite of yourself - He has so much enthusiasm & warm feeling, so much intelligence and general information, so quick sympathy with anything beautiful or touching - I do not think him perfection, & I hope & believe he does not think me so; but I feel I cannot respect him too highly, & that the more I shall know the more I shall find to love & esteem - He seems to me to have a strong judgment & good sense, & I am sure a most undeviating sense of right - He is quite distinguished as a botanist; & is held in very high esteem by all his friends & acquaintances.

Jane Loring to Mary Pierce, 9 May 1847

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

While originally it seemed that an autumn 1847 wedding was imminent, fate intervened. First, Harvard decided to build an addition to the Botanic Garden house where Asa & Jane would live so the nuptials were postponed. Then Jane became ill with jaundice, and lastly and most distressingly, Asa's younger brother George became very sick. According to Hunter Dupree, George came down with typhoid fever. His condition was very bad and he moved out of the Botanic Garden house and moved into the Loring's home in Beverly where he was constantly watched over by Jane. On January 9, 1848, while Jane read to him from the Bible, George Gray passed away.

Finally, in the spring of 1848, more than a full year after they had become engaged, they were married. May 4, 1848 was a lovely spring day. The wedding was beautiful and the reception was held in the Harvard Botanic Garden. The guests walked among the plants and were serenaded by the Aeolian Choir.

The Grays took a short wedding trip to Washington, D.C. in June of 1848 and, upon returning, Jane settled into the house in the garden quickly. More of a problem was her poor health. This kept her from assisting Gray as much as they had both hoped and kept her alone in the house quite a bit as Gray went about his duties. For someone so used to being the mistress of a bustling household, it was quite a change. Her sister offered her advice on dealing with the unexpected loneliness that she was feeling.

My dear little Jeannie,

How grievous I am to hear such sad accounts of you and much do I wish I could go and see you - but that cannot be & I must content myself with writing - They tell me that you are very lonely. ...I think however, as far as I can judge, that a much better plan would be for the Doctor to keep one of his libraries private, and you go down stairs in the morning, as I do, and stay there all day. - You can have one of those charming couches drawn in & watch him & be amused by seeing him work.

Susan Loring Jackson to Jane Loring Gray, December 1848

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

While the Grays never had children of their own, they often had a houseful of nieces and nephews as well as Harvard undergraduates, visiting botanists, scientists, and collectors such as Charles Wright. Jane did her best to aid Asa in his work as well as she could but her health often interfered.

...I believe my fate through life is to be in full drive to catch up with the amount of labour already far ahead - I wake in the morning to think how much there is to do in the day, & go to bed at night thinking how little is accomplished - And my poor husband is waiting for me to finish some necessary things, to take seriously hold & help him; all I do now being some odd tasks of writing now & then -I am afraid he is sadly disappointed as to the famous assistant he was to have when married; it is only many additional things to look after - But then I do not think I have quite had a fair chance, I have been sick so much; & now I sometimes lose a day, & that puts one back so much - I really think I sometimes lose time in feeling there are so many things to do; & scarcely knowing where to begin...

Jane Loring to Mary Pierce, 20 January 1849

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

Jane's legacy was more than the work that she performed for Gray but also the effort to preserve and chronicle his life's work. She organized his correspondence, manuscripts, and papers and deposited them at Harvard. She transcribed and edited a book of important Gray correspondence titled Letters of Asa Gray (1893). She then sent gift copies of the book to major university and garden libraries all over the world.

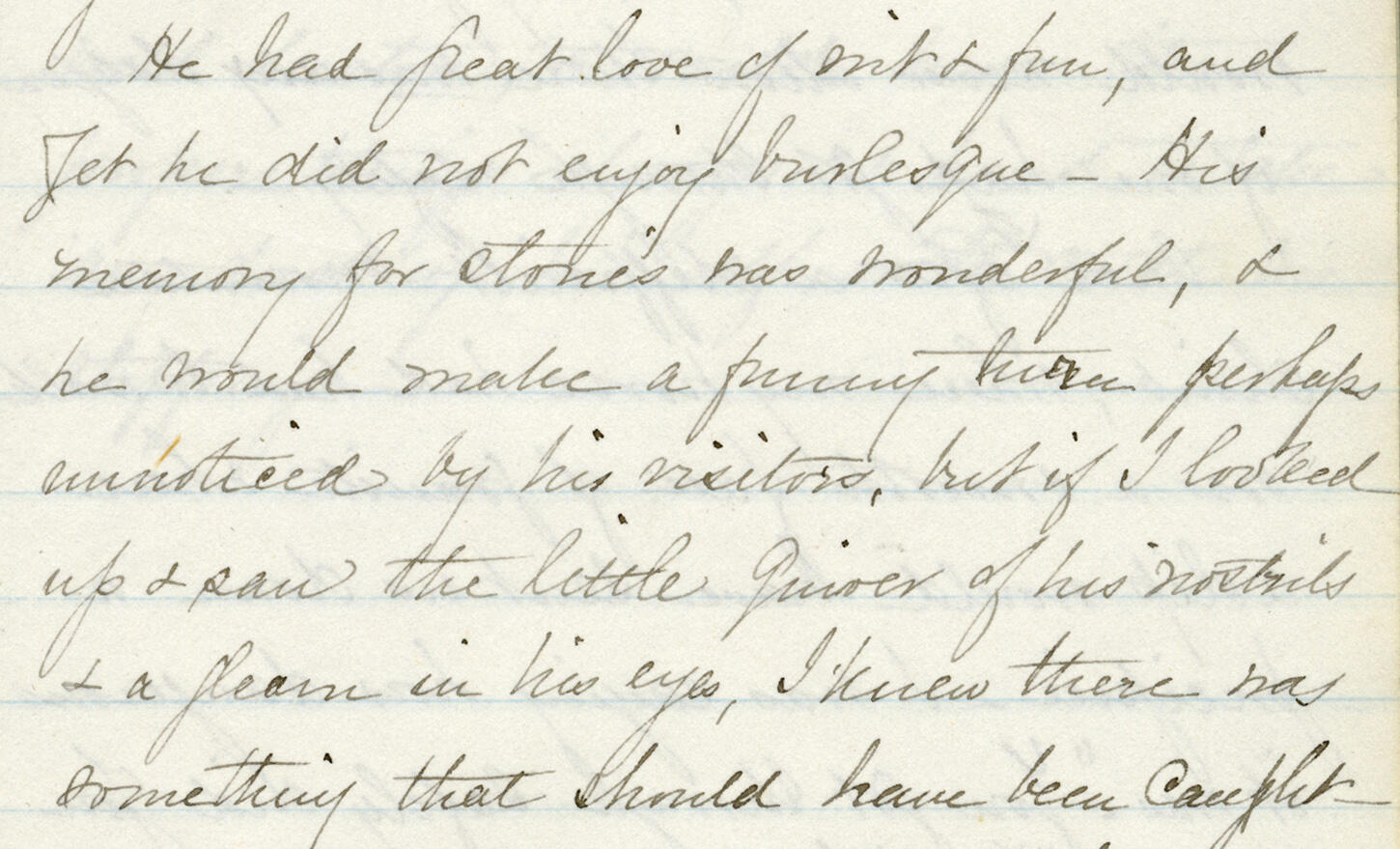

Jane also worked hard to expand and organize a collection of autographs that Asa Gray began in 1893. She toiled diligently to preserve his scientific contributions but also realized the importance of illuminating his more personal characteristics, as in her notes below.

He was quick and impetuous in temper, but the excitement soon over- and one might say of unfailing good nature. He was the cheeriest of household companions, very rarely depressed - only when greatly fagged with some tremendous pressure of work, or some worrying trouble, difficult to settle - very hopeful, with always a happy assurance that everything was going well when he was away, which was sometimes rather trying when his help was needed - and he was extremely fearless.

He had a knack in gathering a bouquet and in arranging it in his hand as he picked, the colors and forms seemed always to fall into their most effective places, and then he would roll them up in a piece of paper to the horror of the on-lookers; but they would bear the carrying so much better when loosely done that one would be surprised how fresh and charming the nosegay turned out to be!

Always on the lookout for plants he would step through the window of a stage-coach without opening the door, when going up a hill, to the alarm of the passengers, if he saw something he wanted - and though in later years he would say at first "My strength is gone, I cannot climb any longer" - yet after a day or two the power would come back and he could still outstrip the younger men.

He was steadfast, faithful in his affections, and with a childlike trust that anyone he wished to see wished to see him - of great simplicity of character and manner, and want of self-consciousness - and yet he had a decided business capacity, and managed money affairs and the many transactions that passed through his hands with great shrewdness and ability.

His feelings were tender & easily touched - so that he did not like to hear or read very moving stories or poetry, especially before people - He had the New England dislike of a display of emotion - But the eyes would moisten readily at anything which moved him in any way.

Because of Jane Lathrop Loring Gray we are allowed a rich glimpse of not only Asa Gray the botanist and champion of Darwin, but also Asa Gray the man, husband, and friend. This is a rich gift that should be acknowledged and celebrated.

Because of Jane Lathrop Loring Gray we are allowed a rich glimpse of not only Asa Gray the botanist and champion of Darwin, but also Asa Gray the man, husband, and friend. This is a rich gift that should be acknowledged and celebrated.

(1)The Lowell Institute traces its roots to an 1836 bequest by John Lowell, Jr., a scion of the prominent New England family that introduced production machinery to the manufacture of cotton goods. In his will, John Lowell, Jr. left one-half of his fortune ($250,000) toward the development of public lectures for Boston residents on the topics of philosophy, natural history, and the arts and sciences. John Amory Lowell, the founder's cousin, was appointed sole trustee of the new Lowell Institute and organized the first lecture series in 1839. As set forth in the will, tuition for lectures was equivalent to the "value of two bushels of wheat." (Lowell Institute Archives at Northeastern University, Boston)

References:

Dupree, A. Hunter.

Asa Gray, 1810-1888.

Cambridge : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1959.

Farlow, W. G. (William Gilson), 1844-1919.

Memoir of Asa Gray 1810-1888.

Read before the National Academy, April 17, 1889.

Gray, Asa, 1810-1888.

Letters of Asa Gray / edited by Jane Loring Gray.

Boston and New York : Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1893.

Asa Gray papers

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

Jane Loring Gray correspondence,

Archives of the Gray Herbarium

Loring Family Correspondence

Litchfield Historical Society

Many thanks to archivist Linda Hocking for her assistance with these letters.