Uses

The Many Uses of Pith Paper: Flowers, Tourist Trinkets and Medicine

Artificial Flowers

Because of its strength and flexibility, pith paper is well suited to the art of making artificial flowers. Artificial flower production was probably first recorded during the Tsin Dynasty (265-420 AD) under Emperor Huey Ti. The paper handles very well, absorbs colors and dyes easily, and produces a very natural appearance when formed into flowers. Additionally, these same attributes allow for excessive handling and detailed work. At the turn of the 19th Century in Canton and Hong Kong, nearly two to three thousand people were employed in the manufacture of artificial flowers, some working on "assembly line" type productions while other workers who were more skilled produced the flowers individually.

Paintings

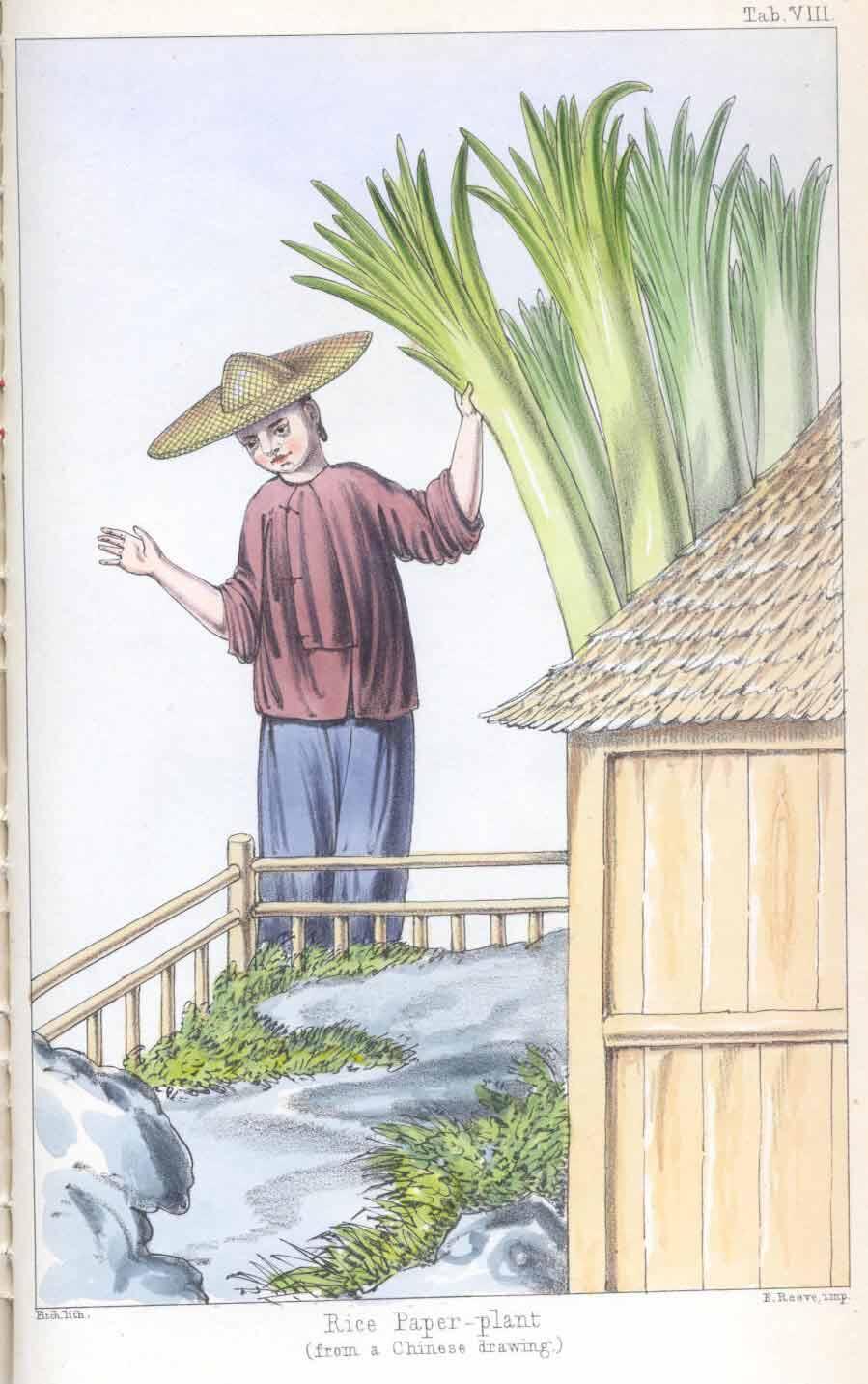

Pith paper as a format for water-based paintings, such as watercolors and tempera, seem to have originated in southern China and became most popular in the west in the 19th century. Western tourists would purchase bound volumes of pith paintings and return with varied images depicting scenes of customs, occupations, costumes, flowers, birds, insects, and butterflies. Occasionally, collections depicting less common themes have appeared; the National Anthropological Archives at the National Museum of Natural History holds an unusual collection of pith paintings depicting scenes of Chinese torture. The pith paper, being so absorbent, are washed in the paints that then create a raised, relief-style image that has a velvety, smooth feel and adds visual depth at the same time. This added aesthetic poses a problem in terms of restoration and conservation in that it renders the paper even more fragile. Typically, pith paintings are "framed" by applying a paste to the back of the image and overlaying a "lining" of another type of paper before adding strips of silk around the edges to complete the "frame", after which they are then usually bound in albums. Along with the samples of pith received by Hooker in 1850, a volume of drawings of Tetrapanax papyriferum were used to illustrate the plant in its natural habitat and the manner in which it is processed to make the paper. The following excerpt comes from Hooker's Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany, Volume II, 1850:

"We are not yet prepared to state what is the plant which yields the and now well-known substance called Rice-paper; but, thanks to the queries inserted from time to time in our 'Journal of Botany,' and to the exertions made by our numerous friends to contribute to the Museum of Economic Botany, now so successfully forming at the Royal Gardens of Kew, we have advanced more than one step towards such a knowledge. In a late number (p. 27 of the present volume) we were enabled to some interesting information relative to the "Rice-paper," through the kindness of Mr. Layton, H.B.M, Consul at Amoy, and we have now the pleasure of communicating some further intelligence, derived from C. J. Braine, Esq., a gentleman who has recently returned from Hong-Kong, bringing a rich collection of living plants for the Royal Gardens of Kew, and many curious vegetable products for the Museum of the same establishment,-together with a thin volume of well-executed drawings by a Chinese artist, on Rice-paper ,-said drawings exhibiting the several stages or conditions of the Rice-paper plant, from the preparation of the seed to the packing of the material for exportation.

"We have selected two out of the eleven of these drawings for our Journal, as illustrative, in the one case, of the growing plant, and in the other, of the mode of cutting out, or forming, the sheets of this paper. The first of these (Tab, VIII.) does, indeed, exhibit the growing plant as of so strange a character, that no botanist to whom we have shown it can conjecture to what family it may belong; and one is naturally led to inquire how far the correctness is to be depended upon; more especially as the presentation is quite at variance with a Chinese figure, said to be that of the Rice-paper plant, in the possession of J. Reeves, Esq., of Clapham, alluded to at p, 29, supra. We should, however, be disposed to think more favourably of the correctness of a series of drawings made expressly for the purpose of illustrating the History of the "Rice-paper," than of a solitary and isolated figure expressly required to he made by a European, In this latter case "John Chinaman" is, perhaps, not wholly to be trusted."

Medicinal Uses

Although largely used for paintings, trinkets and artificial flowers, elements of Tetrapanax papyriferum have also been used for medicinal purposes. The pollen from the flowers of the plant are said to aid hemorrhoids, the stem is said to act as a sedative in addition to being used for coughs and bronchitis. The pith paper itself has occasionally been used as surgical dressing because ability to absorb fluids. In 1590, Shizhen Li's publication Pen ts'ao kang mu (Chinese Materia Medica) describes the many medicinal uses of Tetrapanax papyriferum in the following manner:

"The stalks of those plants which grow in the hills are large, several inches in circumference. The taste and virtues of this plant are sweet, cooling and innocuous. It aids the secretions, stops diarrhoea and excess of urine, and helps the expectorations. A tincture of the burnt stalks reduced to powder is good for lockjaw." [Translation from Seemann's journal excerpt in J Bot Misc Kew]

"Tetrapanax payriferum produces an elegant paper that has numerous uses from the decorative to the practical. As illustrated above, there are several collections of pith paper paintings in circulation and in museum collections today. Knowing this, it is interesting to note that they were originally produced as ephemeral tourist trinkets."