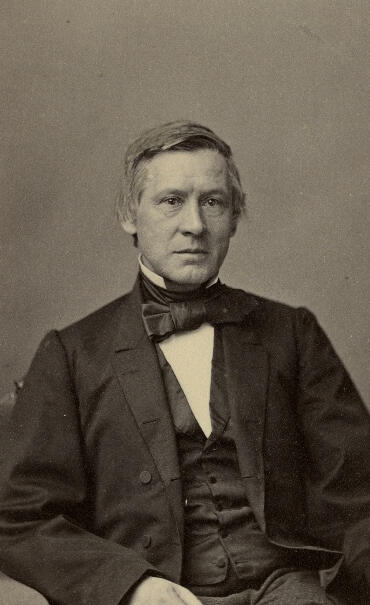

The Founding: Asa Gray and Sir William Jackson Hooker

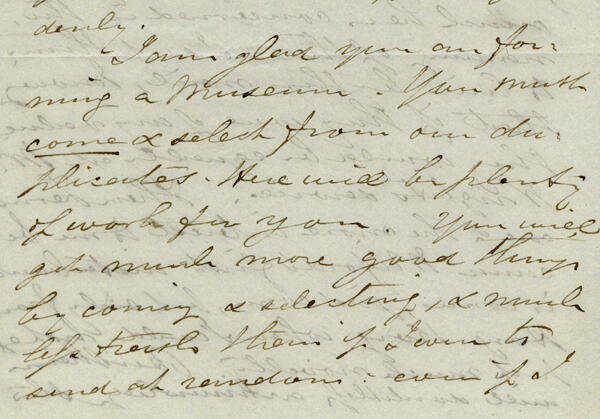

In a letter dated April 30, 1858, Asa Gray wrote to Sir William Jackson Hooker saying "I must tell you that in humble imitation of Kew, I am going to establish a museum of vegetable products, etc., in our university." Thus began the Botanical Museum, originally called the Museum of Vegetable Products. William Hooker, director of the Royal Botanic Museum at Kew and good friend of Asa Gray, sent a donation of duplicate materials from Kew that formed the first collection of the Botanical Museum. Hooker originally suggested that Gray visit Kew himself to choose from the duplicates there, but Gray declined his invitation at the time. In addition to specimens sent from Hooker, Gray mentioned in his letters that he would be asking his students and correspondents to send him "every sort of vegetable thing" to help build the Museum.

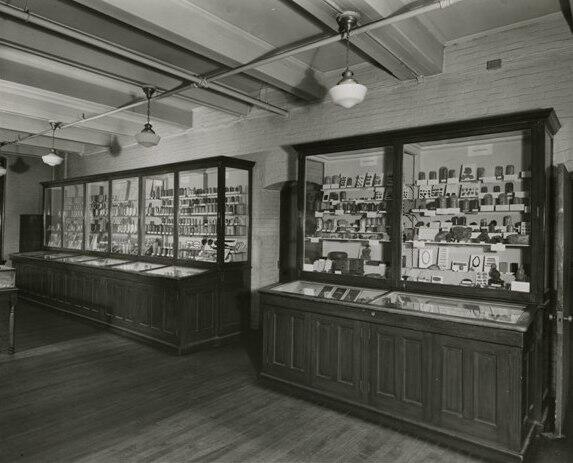

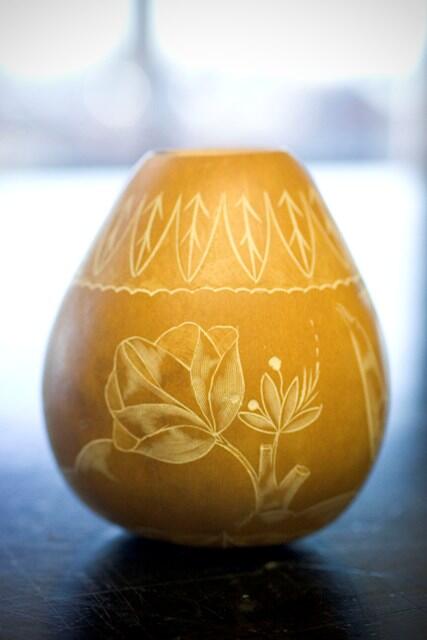

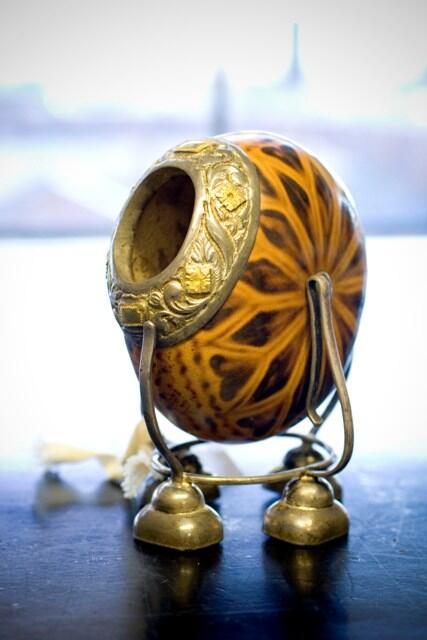

The collection began with wood samples, cones, nuts, palms, and the like; materials that were valuable in teaching but not suited for public exhibition. Gray's vision for the Museum was in favor of instruction and not intended for financial gain or showmanship. In the early 1870s the collections were kept in ill-suited glass cases at the Botanic Garden. Later they were transferred to Harvard Hall. It was evident from the beginning that a space should be dedicated solely to the interesting materials being collected, as illustrated by an excerpt from The Development of Harvard University since the inauguration of President Eliot, 1869-1929: "Some of its [the Botanical Museum's] rare but grotesque objects proved far too tempting to students and were apt to roll mysteriously down aisles and stairways, giving incident to otherwise unexciting lectures." Conditions would soon improve.

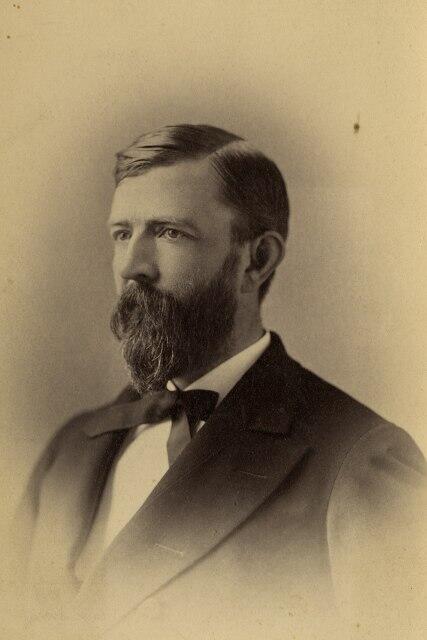

George Lincoln Goodale: First Director, 1888

Following Gray's death in 1888, George Lincoln Goodale became the first director of the Botanical Museum. Goodale was originally from Saco, Maine. He had been an apprentice in his father's apothecary store for several years, where he acquired an interest in drugs and chemicals. He graduated from Amherst College in 1860 with an A.B. and in 1863 received his M.D. from the Harvard Medical School. Goodale practiced medicine for three years in Portland, Maine before accepting a professorship at Bowdoin College where he taught botany, zoology, and chemistry. In 1872 he accepted an appointment at Harvard as Instructor in Botany and University Lecturer in Vegetable Physiology. In 1878 he became full Professor of Botany. In 1888 Dr. Goodale was appointed Fisher Professor of Natural History, a position he held until 1909.

George Goodale contributed to the Botanical Museum in many ways. He saw great prospects for the future, including a space with good light, attractive exhibits, accurate labels and interesting objects. Goodale was instrumental in acquiring funds for the Botanical Museum. L.B. Robinson wrote of Goodale "his soliciting always had a fine dignity. It was clear that it was impersonal in nature, for high purpose and unselfish ends." Goodale acquired the funds for the building, cases and other fittings. He then oversaw the process of building a structure suitable for the Museum. It was completed in 1890 and housed a museum display, collections space, a large lecture room, other smaller lecture rooms and laboratories for staff. To complement the new building, Goodale went in search of exhibits to draw the curiosity of the public. Through generous donations by Elizabeth Ware and her daughter, Mary Lee Ware, he was able to commission a collection of glass flowers by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka of Meissen, Germany.

George Goodale contributed to the Botanical Museum in many ways. He saw great prospects for the future, including a space with good light, attractive exhibits, accurate labels and interesting objects. Goodale was instrumental in acquiring funds for the Botanical Museum. L.B. Robinson wrote of Goodale "his soliciting always had a fine dignity. It was clear that it was impersonal in nature, for high purpose and unselfish ends." Goodale acquired the funds for the building, cases and other fittings. He then oversaw the process of building a structure suitable for the Museum. It was completed in 1890 and housed a museum display, collections space, a large lecture room, other smaller lecture rooms and laboratories for staff. To complement the new building, Goodale went in search of exhibits to draw the curiosity of the public. Through generous donations by Elizabeth Ware and her daughter, Mary Lee Ware, he was able to commission a collection of glass flowers by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka of Meissen, Germany.

Dr. Goodale gave painstaking attention to his exhibits to ensure that the labeling and arrangement was perfect. In a segment written for Harvard Graduates' Magazine in 1896 Dr. Goodale wrote "It has been the purpose of the one in charge [himself] to keep constantly in mind the admirable definition of ’museum’ given by the lamented Professor Goode of the National Museum at Washington, namely, 'a collection of labels fully illustrated by specimens.' As far as possible, all of the sections have been well-labeled and have been kept in proper proportion. The result has been, so far as can be judged by the apparent interest of visitors, well worth the trouble taken." With a feature exhibit as notable as the glass flowers, Dr. Goodale was then able to create clever and attractive exhibits of vegetable structures and products in adjacent rooms to inform the public. It was at this time that Goodale realized the other botanical establishments in the University were devoting their attention to plants as they occur in the wild, and so he thought the Museum would benefit more if prominence were given to the economic side of botany. In 1890 and 1891 Goodale made a journey around the world largely in the interests of the Botanical Museum. In 1909 he retired from most of his official duties but accepted the position of Honorary Curator of the Botanical Museum.

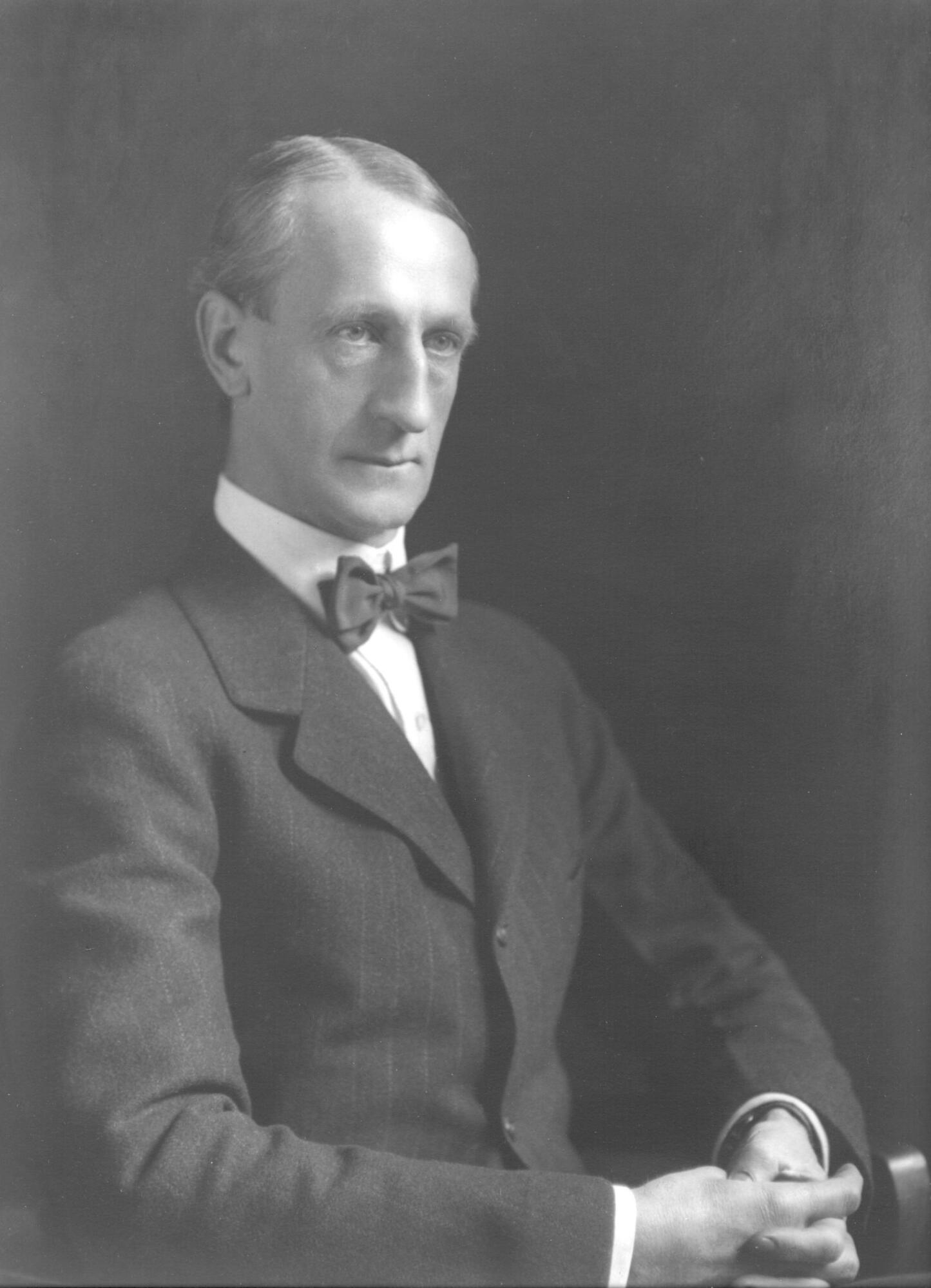

Oakes Ames: Director from 1923-1945

In 1923 Dr. Goodale was very weak, having suffered a long illness. It was on September 1st of this year that Oakes Ames was appointed Curator of the Botanical Museum. Ames had visited an anxious Goodale at his home, who claimed he had heard rumors that when he passed away the Botanical Museum would be "practically given up." Goodale secured a promise from Ames that he would stand by the museum should anything happen to him. The following May, Ames returned to the United States from an orchid collecting expedition in Honduras just in time to serve as a pallbearer in Goodale's funeral.

Ames had spent many years in the study of economic botany, and had built up a reference collection at the Bussey Institution, which was transferred to the Museum. He also placed his own extensive library on economic botany at the service of the Museum. Oakes Ames admits that when he began his duties as Curator for the Botanical Museum he felt inadequate for the task. In his journal he wrote of the unattractiveness of the building; focusing on details such as the heavy ceiling beams and the "ugly golden oak cases" which he felt brought about a melancholy atmosphere. Through donations; mainly those of Mary Lee Ware and Susan Minns, Ames was able to undertake some work on the Museum. The golden oak cases were moved, and new table cases were brought in for the landing.

Ames had spent many years in the study of economic botany, and had built up a reference collection at the Bussey Institution, which was transferred to the Museum. He also placed his own extensive library on economic botany at the service of the Museum. Oakes Ames admits that when he began his duties as Curator for the Botanical Museum he felt inadequate for the task. In his journal he wrote of the unattractiveness of the building; focusing on details such as the heavy ceiling beams and the "ugly golden oak cases" which he felt brought about a melancholy atmosphere. Through donations; mainly those of Mary Lee Ware and Susan Minns, Ames was able to undertake some work on the Museum. The golden oak cases were moved, and new table cases were brought in for the landing.

In June of 1932 the first issue of Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University was released. This journal was used for the publication of research done by the staff and students of the Museum, and were produced by the Museum's own printing shop. The leaflets served as an important source in acquiring an international reputation for the Museum. These publications were sent to botanical institutions in the Americas, Europe and Asia, where they were very successful.

Though reluctant to assume leadership of the Museum at first, Oakes Ames both broadened and strengthened the Botanical Museum. Under his directorship, the building itself was refitted, necessary funds were acquired, and its development in the field of economic botany was greatly enhanced.

Economic Botany exhibits at the Botanical Musuem, circa 1923Paul Christoph Mangelsdorf (1945-1967)

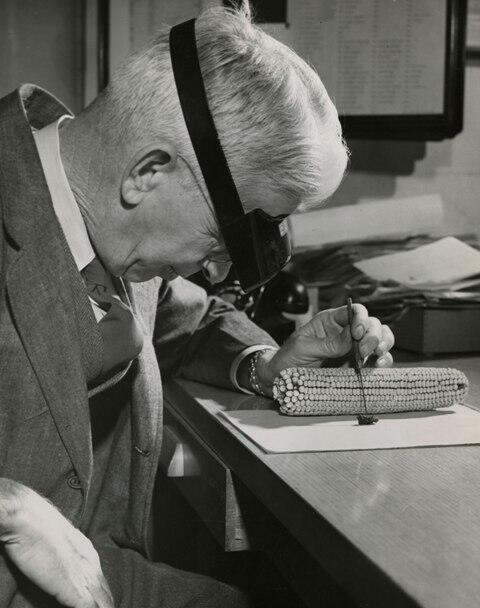

In 1945 Paul C. Mangelsdorf became the third director of the Botanical Museum. Mangelsdorf was born on July 20, 1899, in Atchinson, Kansas. He majored in agronomy at Kansas State Agricultural College. His first job was with Donald F. Jones, a corn breeder at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Mangelsdorf's work led to his being offered the professorship of economic botany at Harvard; a post that carried with it the directorship of the Botanical Museum. He moved to Harvard in 1940 and remained there until he retired in 1968.

Mangelsdorf was instrumental in attracting a number of outstanding researchers to the Museum who further strengthened the work done in economic botany, paleobotany and orchidology. According to a biography written by Kenneth Thimann, Mangelsdorf was known as a "commanding figure" at Harvard, as well as a devoted teacher. He was devoted to the welfare of Harvard, and the royalties of a patent he held were used to found the Mangelsdorf Chair in Economic Botany. Thimann says: "He was not only a researcher and plantsman, but also a humanitarian deeply interested in the lives of poor farmers everywhere in the world."

Mangelsdorf was instrumental in attracting a number of outstanding researchers to the Museum who further strengthened the work done in economic botany, paleobotany and orchidology. According to a biography written by Kenneth Thimann, Mangelsdorf was known as a "commanding figure" at Harvard, as well as a devoted teacher. He was devoted to the welfare of Harvard, and the royalties of a patent he held were used to found the Mangelsdorf Chair in Economic Botany. Thimann says: "He was not only a researcher and plantsman, but also a humanitarian deeply interested in the lives of poor farmers everywhere in the world."

Richard Evans Schultes (1970-1985)

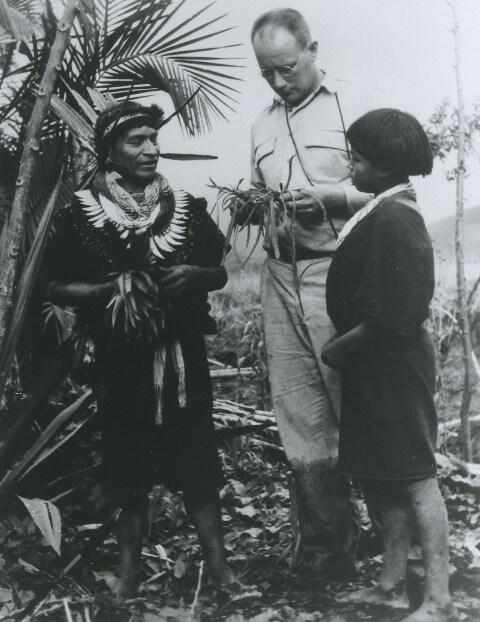

Richard Evans Schultes became the fourth director of the Botanical Museum, beginning in 1970. Originally from Boston, Schultes attended Harvard University as a premed student with a full scholarship. During this time he worked as a clerk in the library of the Harvard Botanical Museum. After taking a course with Oakes Ames called Plants and Human Affairs, he decided to change his major from premed to botany. Immediately after receiving his doctorate, Schultes accepted a position as a research associate of the Harvard Botanical Museum. Schultes spent many years traveling through the Amazon collecting specimens and learning the uses of plants of indigenous peoples. In addition to acting as director of the Botanical Museum, Schultes was also Harvard University faculty. He won numerous awards for his work in economic botany.

Schultes wrote in "Harvard's Botanical Museum: A Centre for World-wide Research," "The [Botanical] Museum's activities spread not only across the lines of scientific fields but they are also international and spread across the globe. Here, from a small, old and certainly not pretentious building in Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, there are threads of research into ancient plant remains in Peru; orchids in Columbia, Venezuela, New Guinea and Burma; new sources of rubbers and medicines in the Amazon Valley; the world's oldest known fossil plants in Canada; studies of climate changes from pollen in borings in Panama; unusual races and strains of corn from Andean countries; wild corn with cobs an inch long from 7,000-year-old archaeological sites in Mexico; vision-producing narcotics in Mexico, South America, India, New Guinea, Burma and elsewhere; toxic plants of Venezuela; plants that have never been analyzed chemically from many places, near and far. In addition to this, its students and visiting scientists come from countries the world over. The Botanical Museum truly is in the forefront in penetration of Nature's secrets in many parts of this shrinking world."

Schultes wrote in "Harvard's Botanical Museum: A Centre for World-wide Research," "The [Botanical] Museum's activities spread not only across the lines of scientific fields but they are also international and spread across the globe. Here, from a small, old and certainly not pretentious building in Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, there are threads of research into ancient plant remains in Peru; orchids in Columbia, Venezuela, New Guinea and Burma; new sources of rubbers and medicines in the Amazon Valley; the world's oldest known fossil plants in Canada; studies of climate changes from pollen in borings in Panama; unusual races and strains of corn from Andean countries; wild corn with cobs an inch long from 7,000-year-old archaeological sites in Mexico; vision-producing narcotics in Mexico, South America, India, New Guinea, Burma and elsewhere; toxic plants of Venezuela; plants that have never been analyzed chemically from many places, near and far. In addition to this, its students and visiting scientists come from countries the world over. The Botanical Museum truly is in the forefront in penetration of Nature's secrets in many parts of this shrinking world."

The Botanical Museum Today

The Botanical Museum today consists of the Economic Botany Collections, the Economic Herbarium of Oakes Ames, the Ware Collection of Glass Models of Plants, the Paleobotanical Collection (including the Pollen Collection and the Margaret Towle Collection of Archaeological Plant Remains), the Economic Botany Library and Archives, the Archives of the Oakes Ames Orchid Library, and the Orchid Library of Oakes Ames and Herbarium. The collections are currently housed in the Harvard Museum of Natural History and the Harvard University Herbaria.

References

Bailey, I. W. Botany and its applications at Harvard : a report to the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 1945.

Current Biography, (1995) v. 56 (3), March, p. 41-46.

The Development of Harvard University since the inauguration of President Eliot, 1869-1929. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930.

Economic Botany Archives, Harvard University. Archives of the Botanical Museum.

Gray, Asa. Letters of Asa Gray (1893). New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co.

Gray Herbarium Archives, Harvard University. Correspondence of Asa Gray.

Gray Herbarium Archives, Harvard University. Correspondence of William Hooker.

Harvard Gazette (1990), September 28, p. 11-12.

Jackson, Robert Tracy. (1923) George Lincoln Goodale. Harvard Graduate's Magazine V. 32, p. 54-59.

Kahn, E. J., Jr. Jungle Botanist. The New Yorker (1992), v. 68, p. 35-58.

Lessem, Don. The plant man: Richard Schultes: the life and times of a gentleman and a scholar. Boston Globe Magazine (1987), p. 18-19, 29-36.

Schultes, R. E. 1965. Harvard’s Botanical Museum—a centre for world-wide research.In (Ed. G. Bowden) Journey through New England—a guide. Boston, Mass. 68-69.

Thimann, Kenneth Vivian. (1991) Paul Christoph Mangelsdorf (July 20, 1899-July 22, 1989). Philadelphia: The Society, p. 467-472.