Identifying the Elusive Plant

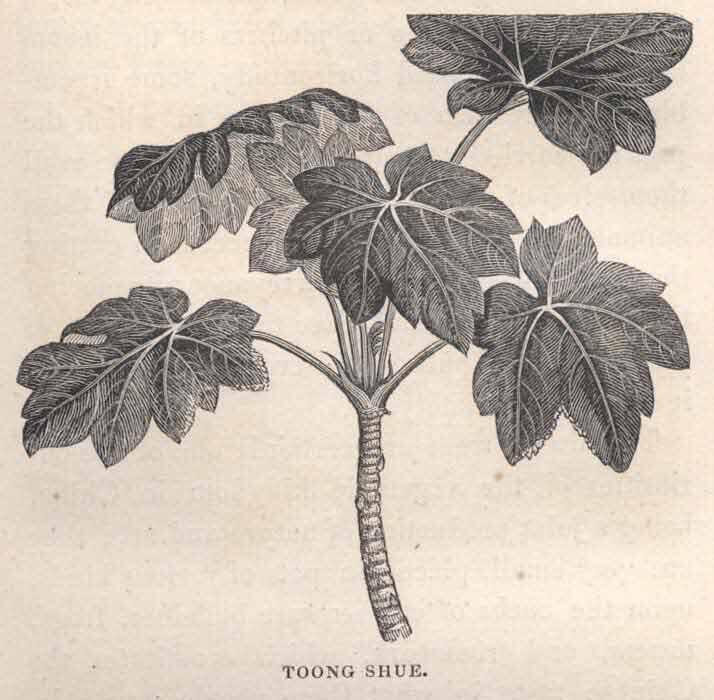

Although pith paper was in use and mentioned as early as the Tsin Dynasty (265-420 AD), it wasn't until 1834 that an adequate image of Tetrapanax papyriferum was seen in the western world in George Bennett's Wanderings in New South Wales. A local Chinese artist created this representation and Bennett identifies the plant by its eastern name,"Toong Shue". He had hoped that the small drawing would "assist persons visiting China to procure, if possible, specimens in flower and fructification". By 1852, Hooker had finally received a live specimen of Tetrapanax papyiferum and concluded that the "rice paper" plant is part of the Araliaceous family and as a result of this, he renames it Aralia ? Papyrifera, Hook.:

From Bennett's Wanderings in New South Wales

"We had flattered ourselves that the question respecting the origin of the Chinese Rice-paper had been set at rest by the results of our inquiries as related in the pages of this Journal, namely, that it was the product of a plant peculiar to the island of Formosa, to which we believed we had sufficient materials for assigning the name of Aralia? papyrifera. (See our figure and description, p. 50, Tab. I., II., of the present volume.) Other plants, it is true, had been suggested; but either the medullary substance proved, on investigation, like the "Shola," not to confirm the opinion, or there was no opportunity of coming to a knowledge of the nature of the plant suspected. Our own reasons for believing the Aralia? to be the plant are before the public, and they have, in our minds, been substantiated by subsequent inquiries, particularly by those instituted by the Messrs. Bowring, father and son, at Hong-Kong. These gentlemen have been indefatigable in their searches. They have procured for us specimens of the stem, of the pith, numerous packets of the paper as prepared for commerce, etc.; and now at length we have the high gratification of saying, that out of four separate cases sent by the Overland Mail, on two different occasions, two living plants arrived in a healthy state at the Royal Gardens of Kew."

Hooker was working with a J. H. Layton, consul at Amoy, in order to obtain a live specimen for study and comparison. Unfortunately, Mr. Layton died, but his widow continued to try to procure a live plant. This passage illustrates the extreme difficulty, the western botanists endured in order to obtain a living specimen:

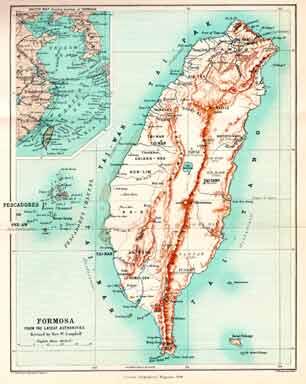

"As far as I could learn," this lady says, "it is only really known to grow in the deep swampy forests of the north of Formosa, though said in books to be found, in these later years, in one other part of China and formerly in many. One thing is certain, that all the Rice-paper met with in Fokien and the south is pith from the island Hu-nan, or Ho-nan (as the Amoy call it),-Formosa. The tree must grow there to a good size, for I was again informed I could not well have a 'tree' brought over, as it would be too large to manage on the way. Great danger and risk attend the men who go into the forests to procure the stems, where the aborigines come suddenly upon them and take away their lives: so that it is customary to have a guard of soldiers on the occasion. At one time it seemed quite certain that my efforts to procure a plant would have been supported by all the mandarin force on that part of the island, for the late brave old Chinese Admiral at Amoy took the matter in hand for me, and sent orders for one to be obtained, and sent back in one of the imperial junks employed to take troops to Formosa; but before it could reach me he was dead. I did not, myself, bring home with me the dead and withered specimen you received, for it did not reach Amoy in time: but I had arranged with a friend to take charge of it, who unfortunately forwarded it to me by way of the Cape instead of sending it overland: for, indeed, it had already been several months in the case in China. One of the two Chinamen, whom I had long before sent over in a junk for the purpose, returned with a small root when I was too ill to take care of it; but it had several green leaves when I took it with me on board ship for England, and this was I think entirely killed by the brown ants. The man who obtained this, assured me that the 'large tree' he procured had died while he waited for a junk, and then after putting out to sea, and being driven back by pirates, he threw the plant overboard, reserving a portion of the stem and some leaves. which I have now in my possession. The second messenger returned soon after my departure, bringing a fine strong plant, thriving beautifully when it was put on board the ship Bentinck, but which died on its passage, and reached your hands without any sign of life."

"As far as I could learn," this lady says, "it is only really known to grow in the deep swampy forests of the north of Formosa, though said in books to be found, in these later years, in one other part of China and formerly in many. One thing is certain, that all the Rice-paper met with in Fokien and the south is pith from the island Hu-nan, or Ho-nan (as the Amoy call it),-Formosa. The tree must grow there to a good size, for I was again informed I could not well have a 'tree' brought over, as it would be too large to manage on the way. Great danger and risk attend the men who go into the forests to procure the stems, where the aborigines come suddenly upon them and take away their lives: so that it is customary to have a guard of soldiers on the occasion. At one time it seemed quite certain that my efforts to procure a plant would have been supported by all the mandarin force on that part of the island, for the late brave old Chinese Admiral at Amoy took the matter in hand for me, and sent orders for one to be obtained, and sent back in one of the imperial junks employed to take troops to Formosa; but before it could reach me he was dead. I did not, myself, bring home with me the dead and withered specimen you received, for it did not reach Amoy in time: but I had arranged with a friend to take charge of it, who unfortunately forwarded it to me by way of the Cape instead of sending it overland: for, indeed, it had already been several months in the case in China. One of the two Chinamen, whom I had long before sent over in a junk for the purpose, returned with a small root when I was too ill to take care of it; but it had several green leaves when I took it with me on board ship for England, and this was I think entirely killed by the brown ants. The man who obtained this, assured me that the 'large tree' he procured had died while he waited for a junk, and then after putting out to sea, and being driven back by pirates, he threw the plant overboard, reserving a portion of the stem and some leaves. which I have now in my possession. The second messenger returned soon after my departure, bringing a fine strong plant, thriving beautifully when it was put on board the ship Bentinck, but which died on its passage, and reached your hands without any sign of life."